As most students poured into the parking lots to leave campus on a gray, tepid Monday afternoon, about 30 of them stuck around to file into a Tureaud Hall second floor classroom, awaiting the beginning of a lecture on the basics of petroleum engineering.

The class’ instructor, Frederick Thurber, teaches the intro-level course and recruits for the department. But his responsibilities, he said, are not just to teach his class the rudimentary science of petroleum engineering, but to help his students decide if the oil industry, with all its instability, is their “cup of tea.”

“If you want something really stable, go become a high school teacher,” he said. “That’s very stable.”

The petroleum engineering department is a unique one, Thurber said, as few universities have one, and those that do are mostly in oil-producing states.

As the price of oil has plummeted to around $30 per barrel, contributing to the state budget deficit that legislators could mitigate with millions in cuts to higher education funding, the job prospects for students studying petroleum engineering are in doubt.

“This is a real downturn. This is the worst we’ve seen since 1986,” he said. “And not as many [students] will get jobs in the petroleum field.”

There is a strong correlation, Thurber added, between the price of oil and the job prospects for his students.

In 2008, when shale production began to boom, jobs were plentiful and oil prices were still high, he said. Students flocked to the University’s petroleum engineering department with hopes of high salaries after college.

“There used to be multiple job offers with extremely high salaries, and we are not going to see that this year,” he said.

According to the petroleum engineering department there are currently around 925 students with the major, not including freshmen. Over the past 12 years, the number of students studying engineering has nearly doubled, according to the fall semester numbers of an Office of Budget and Planning report.

From 2003 to 2008, College of Engineering enrollment increased by nine students. Since 2008, when Thurber said shale production took off in the U.S., the numbers increased by more than 2,000 students.

Salaries after college have been high in the past with low prices of oil, Thurber said, but that was before enrollment numbers increased so rapidly.

“[In 2008], we started producing at rates higher than even Saudi Arabia, and everybody and their brother started coming into the industry, and our numbers just swelled,” he said.

A host of factors have driven oil prices down, and are expected to keep them down at least for the next two years, said economics assistant professor Daniel Brent.

Brent said Iran’s sanctions being lifted and OPEC’s decision to keep producing oil have flooded the supply side of the market. And China, a large oil consumer, has been using less oil, drying up the demand side.

But he cautioned students against basing their career choices off the fluctuations of such an unstable industry.

“That’s not to say you shouldn’t do energy or try to get a job in oil and gas,” he said. “But you may want to think about jobs that may place you well in multiple industries and be a little bit more diversified.”

As part of the E. J. Ourso College of Business’ “energy initiative,” a partnership with corporations interested in students who have an understanding of energy industries, the University will offer a minor in energy in the upcoming fall semester.

But the minor may come at an inopportune time for students planning on going into the oil industry.

Assistant Dean for Academic Programs at the College of Business, Ashley Junek, said the minor was driven by demand in the industry. Many students work in southern, energy producing states, and employers prefer students with some knowledge of the field.

Junek said about 20 students have contacted her asking when the energy minor will become available. The minor will allow students to select “approved electives” that tailor to their interests, she said.

“The hope is that with that flexibility, as other energy courses become available, maybe they’re about alternative energy resources, that would help,” she said.

Thurber also said flexibility is important for his students, as those who study petroleum engineering should be able to find jobs in other industries if the oil market is hurting.

Petroleum engineering sophomore Ashlyn Albers became interested in the industry from hearing about her geologist uncle’s experiences on oil rigs growing up.

Some of Albers’ professors have addressed the state of the oil industry, but she said students don’t have to worry about job prospects until junior or senior year.

“I’ve definitely considered switching [majors],” she said. “But right now I just want to stick it out and see it through. The range that I’ve heard for the industry to come back is between 2017 and 2040. So, I mean it’s a pretty big gap. But it’s gonna come back, so I have that to hope. That’s my one hope right now.”

Oil market brings uncertainty to student job prospects

By Sam Karlin

January 31, 2016

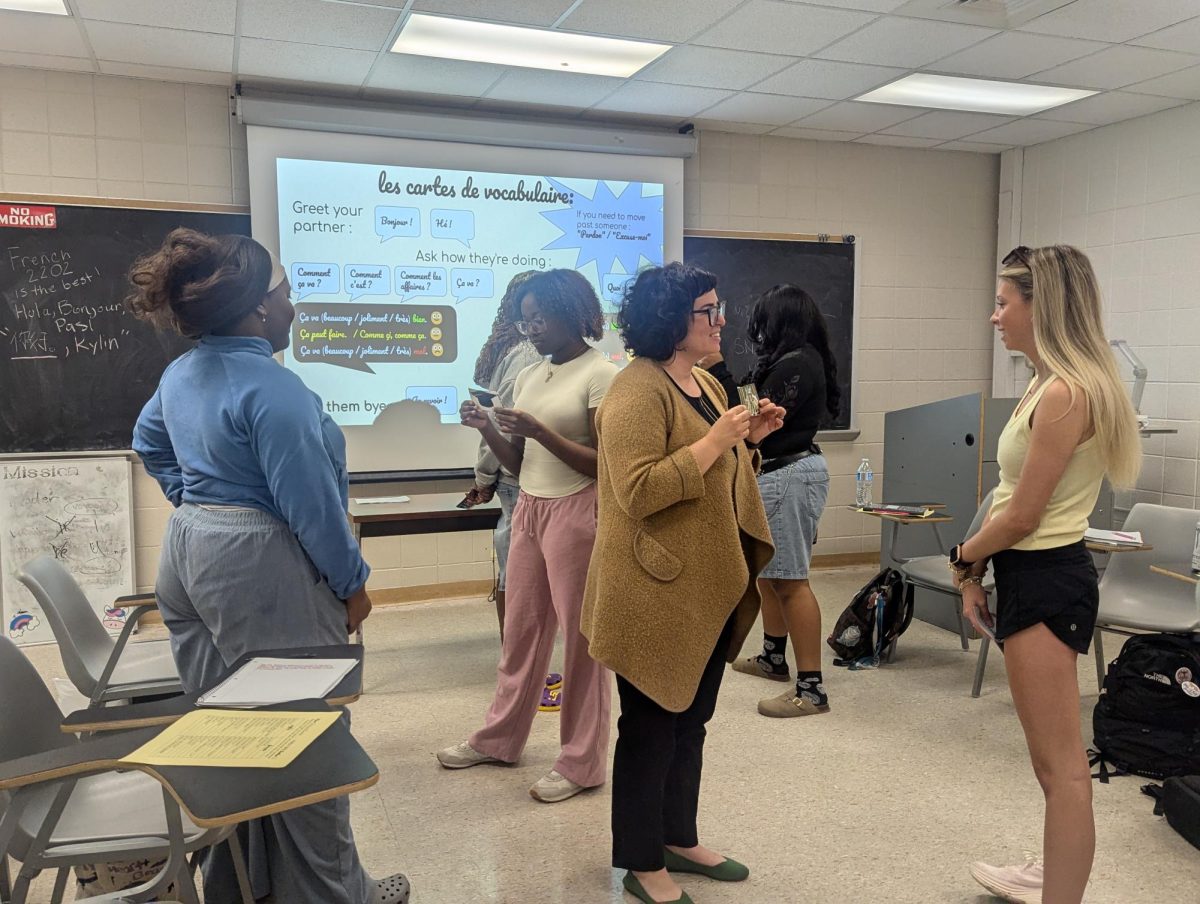

Petroleum engineering instructor Frederick Thurber teaches his intro-level class Monday, Jan. 25, 2016.

More to Discover