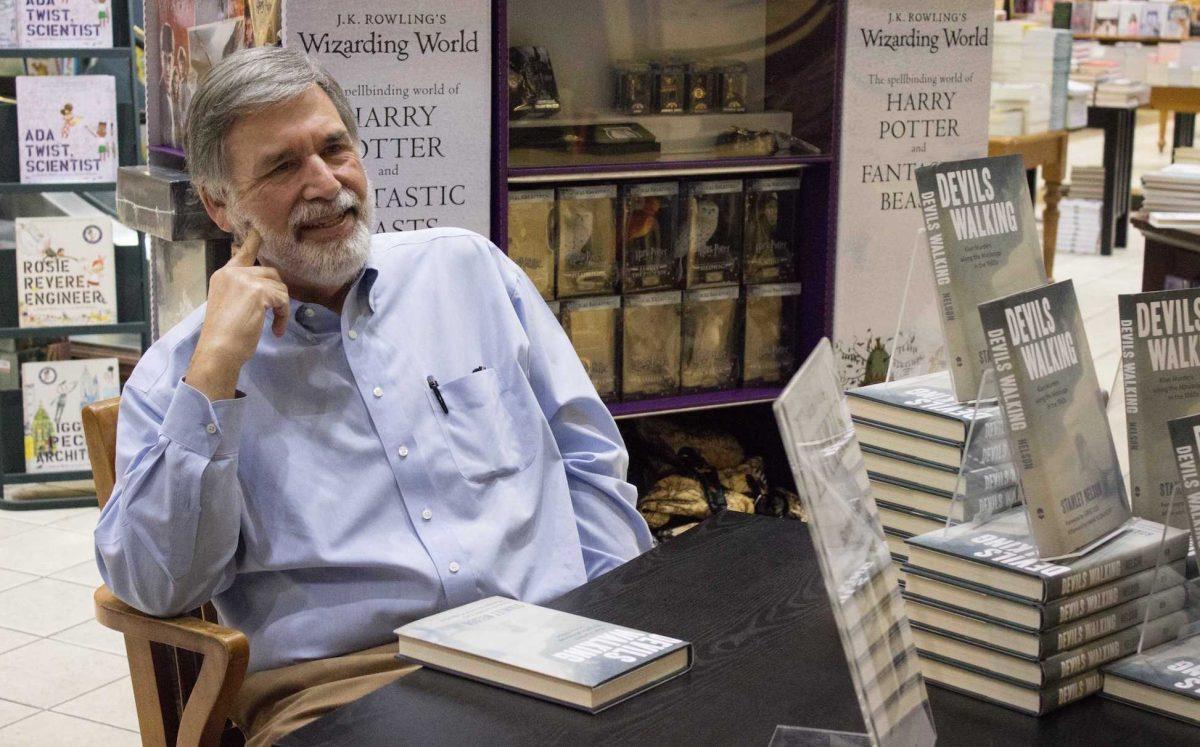

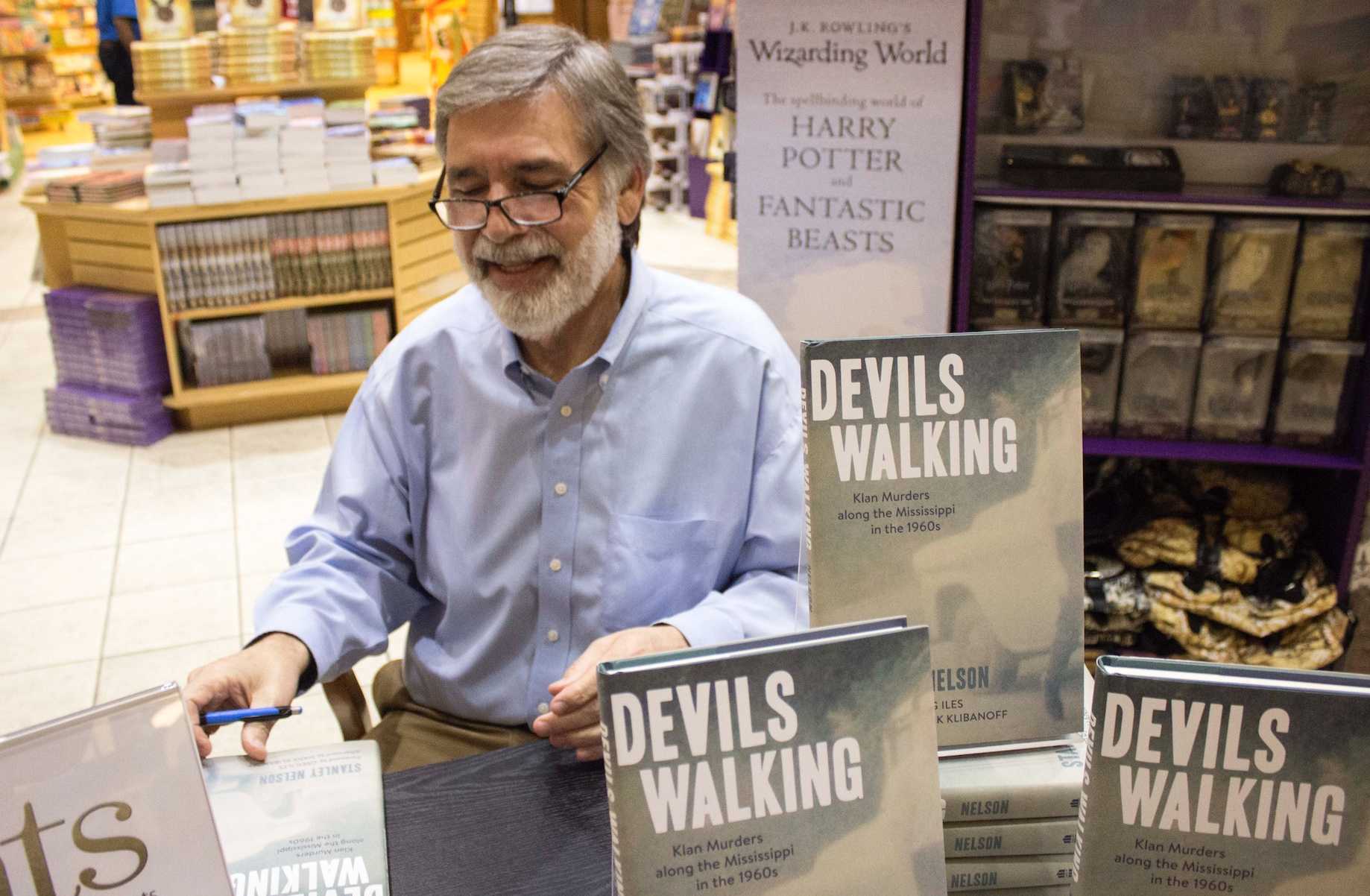

Weekly newspaper editor and now author Stanley Nelson of the Concordia Sentinel in Ferriday, La., has dedicated nearly a decade to telling the stories of eight black murder victims of Ku Klux Klan.

He has written nearly 200 accounts of those killings, becoming a finalist for a 2011 Pulitzer Prize in the process. In October, LSU Press published “Devils Walking: Klan Murders along the Mississippi in the 1960.” The title comes from a code phrase African Americans used to warn their communities that Klansmen were on the move.

In his 237-page, footnoted work, Nelson brings life back to these victims and uncovers heretofore unknown facts about the unsolved murders. The 61-year-old Nelson lays out horrific paths of personal destruction various Klan units took in a two-state killing field, most specifically by the psychotically violent Silver Dollar Group based in Vidalia, La.

Each member of the Silver Dollar Group, whose tentacles spread from east central Louisiana to south central Mississippi, was presented a silver dollar minted the year of their birth as an ID badge.

In spite of the efforts of more than 100 FBI agents investigating these cases in the 1960s, the bureau was able to bring only one of these Klansmen to justice – James Ford Seale of Meadville, Miss. – and that occurred more than 40 years after the fact.

Victims featured in Nelson’s work are Clifton Walker of Woodville, Frank Morris of Ferriday, teenagers Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Moore of Meadville, Miss., Joseph Edwards of Clayton, La., Earl Hodges of Eddiceton, Miss., Ben Chester White of Natchez, and Wharlest Jackson of Natchez.

The FBI re-entered the picture in February 2007 when it announced it would be opening 112 Civil Rights-era (1950-1969) cold cases prompted by the Emmitt Till Act passed by Congress that year. Till was a Chicago teenager who was murdered in northwest Mississippi in the 1950s for whistling at a white woman while visiting relatives.

The signature death of Nelson’s investigations is Morris, a shoe-repair store owner in Ferriday who lived in the rear of his store. On Dec. 10, 1964, he awoke to the sound of breaking glass. Going to the front of his store to investigate, he was confronted by two men, one threatening him with a shotgun and the other dousing the store and Morris with a gasoline. A match was tossed and the gasoline exploded, setting the shop and its owner ablaze.

Morris ran to a nearby service station and was transported to the hospital by two police officers. He was scorched over 95 percent of his body. He survived for four days before succumbing to the burns.

He is the only known Klan victim to have physically described his attackers, though he adamantly claimed to FBI agents, local police, a Catholic priest, and a friend not to know the assailants. Nelson said the death of Morris, who had been well liked by area whites and blacks alike, shocked the town.

Parts of his store’s foundation remains today along the main highway into Ferriday. The case was never officially solved, at the time or when it was reopened, but Nelson’s own sleuthing and more than nearly a hundred interviews allowed him to identify the two men who killed Morris, as well as the deputy sheriff behind the crime.

One of the suspects, a Rayville man and a member of the Klan, was investigated by a grand jury but died of cancer in 2013 before jurors could issue their findings. The other suspect and the deputy, also Klan members, died some two decades ago.

After initially learning about Frank Morris’ case 43 years after it occurred, Nelson wrote a story about it for The Sentinel. A few weeks later, he received a phone call from Rosa Williams, Morris’ granddaughter who was 12 years old at the time of his death. She had heard about the story from a Ferriday friend and wanted to thank Nelson.

Growing up, no one ever told Williams about what happened to her grandfather, learning the gory details on when she became older. She had spent her life praying that someone would do something about the injustice.

Through Williams, Nelson began to embrace a goal of helping other families in isolation of uncertainty, grief and pain to find closures. “It was very moving to me because I thought, ‘How would I feel if it was me?’”

And Nelson started to delve deeper into cases from the area.

“There’s never been any true investigation on into this. You feel like you’re the only person in the world who cares that no one cares about you. To me, that is a lesson we need to learn about our communities. There are people suffering on both sides of these tragedies, and (the feeling) doesn’t go away, they often feel abandoned.”

Along the way, Nelson became involved with the National Civil Rights Cold Case Project and has worked closely with LSU’s Cold Case Project, other reporters, universities, and former FBI agents who originally worked the cases in an effort to resolve them.

His work has earned him a number of prestigious awards. But the Ferriday native and 1977 graduate of Louisiana Tech with a degree in journalism, also had to put out a weekly newspaper each with a newsroom staff of two. That meant a lot of night and weekend work.

The major difficulty in investigating many of these killings is that the suspects and a good many witnesses are dead. He interviews relatives and friends of victims, members of the communities, and FBI investigative reports, mostly obtained by the LSU Cold Case Project under the Freedom of Information Act.

“It’s amazing to know you are looking at documents about something that happened half a century ago. And from there you are searching for those people to find out where there are today.”

Nelson has had book-signing events throughout Louisiana and Mississippi and in Memphis and Washington, D.C., since his book became available two months ago.

Nelson’s current goal is to help Joseph Edward’s family find his body and to give them some closure. Edwards was 23 years old in July 1964 when he disappeared after being pulled over on the Ferriday-Vidalia Highway by the Vidalia police chief and the chief deputy of Concordia Parish, the same man involved with the Frank Morris fire-bombing five months later.

Based on witness accounts, Nelson believes Edwards ran from police and was chased down by a police car on a levee and killed. He subsequently buried at was at a levee construction site nearby.

Throughout the last nine years, community reaction to Nelson’s digging up nightmares from the past, for the most part, has been one of interest. There has been praise and criticism, as is normally the case to controversial stories.

“(Readers) had to give me the time so I could show them (the victims) as human beings, not just some person that lived 50 years ago. I had to prove to them why it was important.”

Nelson has been working for the Hanna Newspapers of Louisiana for 35 years. Backlash over Nelson’s writings was not a real concern for Sam Hanna Jr. t owner of The Concordia Sentinel, and The Ouachita Citizen in Monroe and The Franklin Sun.

“Stanley is very fair with his reporting, he gives everyone and anyone a chance to speak,” said Hanna. “He deserves a great deal of gratitude for taking on such a controversial topic, even in this day and age.”

Nelson is considering writing a second book about what such tragedies do to the victims’ and to the murderers’ families.

“Devils Walking” is raw and heartbreaking, and a painful but historic reminder of the South’s past. However, it allows voices from the graves, through Nelson, to preserve memories. Justice is briefly served. More lasting, however, is the fact that the stories bring some sort of closure to next-of-kin who, until now, could only speculate as to what happened to a loved one lost.

Newspaper editor turned author publishes account of 1960s Klan Murders through LSU Press

December 18, 2016

Author and newspaper editor Stanley Nelson at a recent book signing for his new book, “Devils Walking” on the KKK violence in east central Louisiana and southwestern Mississippi during the 1960s.

More to Discover