Allen Coney

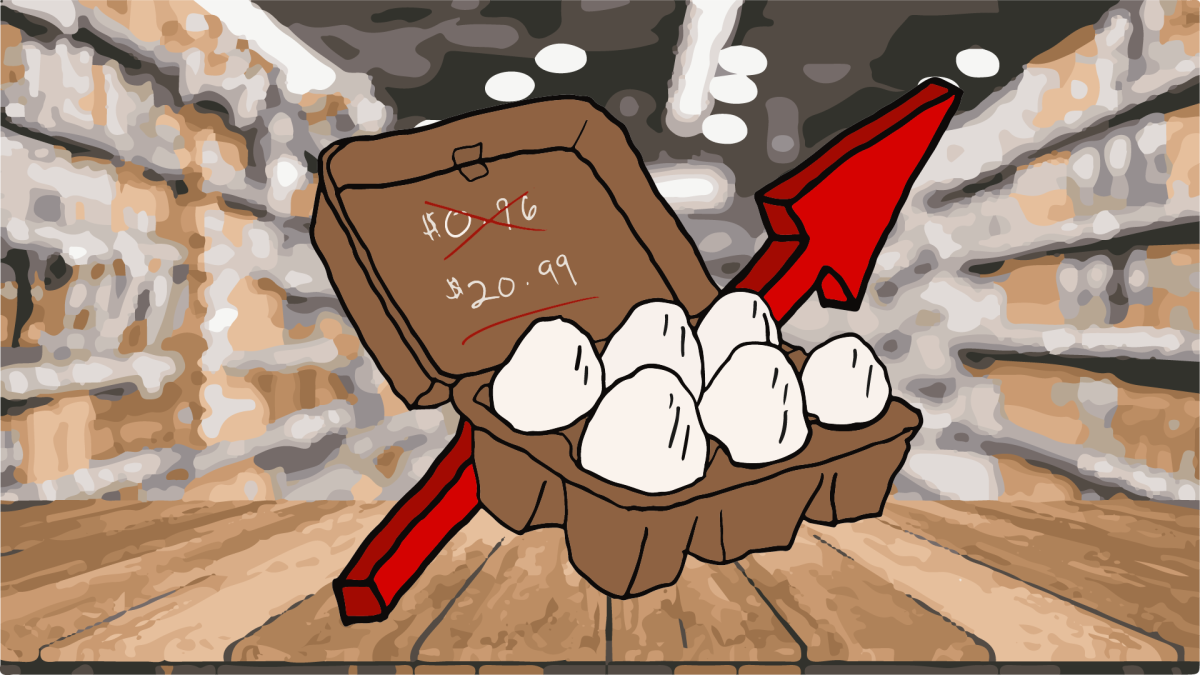

Egg Prices

In the past weeks eggs have become a hot commodity, with Trader Joe’s seemingly always out of stock, Walmart’s prices springing from around $4 to more than $8 and Costco limiting the number of cartons customers can purchase.

Though eggs prices have risen over the past year, the swift spike in pricing can be attributed to the rise of the avian flu in chickens and other bird populations.

The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention says bird flu is incredibly contagious between birds and is capable of killing domestic birds, with some birds carrying the disease without showing symptoms. Though the CDC says bird flu has been around since the late 1800s, a new strain of the virus emerged in aquatic bird populations in 2020. The strain then moved to infect hundreds of other species like ducks, swans and chickens.

According to the CDC, the H5N1 strain of the bird flu only took a few months to infect humans and non-bird animals after its emergence. In 2021 the virus emerged in Europe and East Asian. Other variants of the virus began to spread, killing 18 people in China.

The next few years saw small but contained cases across the world. It wasn’t until late 2022 that the virus began appearing in the U.S., infecting birds, foxes and other wild animals. Bird flu began to clearly affect farm animals across the U.S. last year. When these animals contracted the infection, so did humans.

Last month, a patient in Louisiana died from bird flu, marking the first U.S. death from the virus. Currently, the CDC and other agencies are working to minimize the spread of the infection.

William Strickland, an assistant extension agent at LSU’s AgCenter and the university’s resident bird flu expert, explained the virus and its impact on farmers, animals and the agricultural industry. He said the bird flu is “fairly highly contagious and has a very high mortality rate in our poultry populations,” and the virus and the consequential egg shortage are “probably not going anywhere anytime soon.”

Currently, many birds are being tested and observed for symptoms. If a group of birds in a population seem to be contracting the virus and dying, farmers begin to depopulate the group with the help of the U.S. Department of Agriculture to stop the spread of the virus.

Strickland points to the fact the virus is highly contagious and that whole groups of chickens have to be killed to stop the spread of the virus to explain the strain on the production of eggs.

When farmers realize their animals are infected, they must follow guidelines to stop the spread.

Strickland highlighted the problems that come after a farmer has to depopulate their flock, including having to find a way to safely discard the dead chickens to stop the spread of the virus. Before the farmer can repopulate the farm, they have to check with the USDA to make sure it is safe and clean from bird flu.

Though the first and only human death from avian influenza happened here in Louisiana, Strickland cites the CDC in their knowledge that there is not much risk to humans. He also cites the USDA, saying that properly handling and cooking meat and eggs kills the virus.

“There’s a lot of other USDA safeguards in place to keep it out…” Strickland said. “As long as you properly handle and cook them, those products are safe to eat.”

For anyone worried about domesticated birds, such as chickens and turkeys, Strickland advised contacting the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry. For wild birds, he said to contact the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

Daniel Keniston, an economics professor at LSU, explained how a drastic shift in egg prices and the bird flu are affecting citizens’ pockets. Keniston said one of the reasons for such a big shift could be because of how universal and prominent eggs are in the American diet.

If the high prices of eggs continue, Keniston said that people’s tastes may change, and they may adopt different eating habits to soften the financial blow. He proposed that some people may stop buying eggs or people will develop a new way of getting eggs, such as importing them.

Keniston explained product shortage and a steep rise of prices has occurred before, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“That was driven more by demand than supply, but during Covid we saw bottles of hand sanitizer going for $100 and stuff like that,” Keniston said. “You can get these rapid shifts in prices.”

As an economics professor, Keniston said seeing eggs’ price-shifting dynamic offers students a chance to apply what they learn in the classroom to real life. He even thinks economics professors will use the egg shortage as an example in their classes over the next decade.

“It’s very gratifying to see what we call ECON 2000 at work here,” Keniston said. “It’s a classic case of a reduction in supply causing shortages and then causing price increases. It’s absolutely what we teach in Econ 2000.”