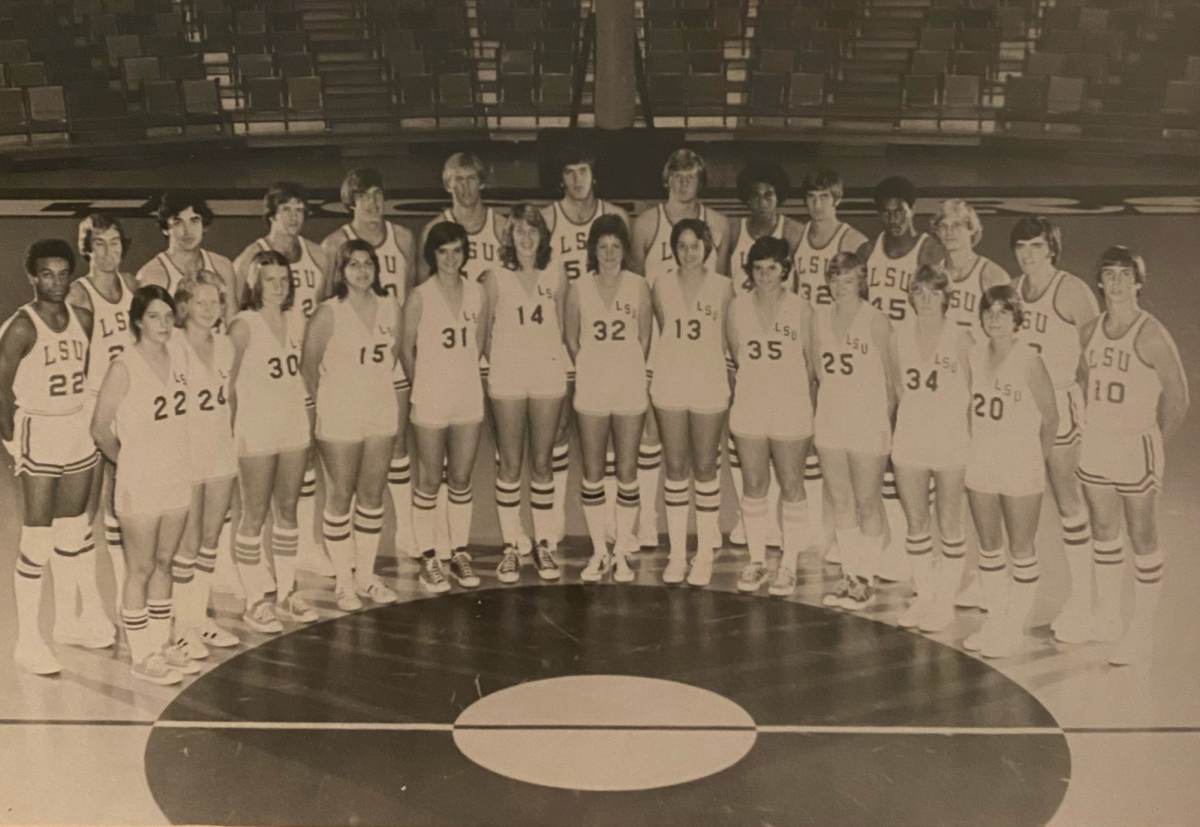

2025 makes 50 years since women’s basketball became an official varsity sport at LSU in 1975.

The founding years were nowhere near the spectacle the team is now. There was no extravagant locker room, no NIL and almost no fans. Instead, the team was staying in makeshift dorms, flying the team plane and a budding championship contender.

Jinks Coleman was the inaugural head coach for the “Ben-Gals.” She coached the team when it was still a club in 1973. Coleman even used money from her pocket to finance scholarships for women’s basketball, according to LSU.

“She had a lot of personalities to handle,” Lenette Caldwell Romero said. “I don’t know if you want to call it egos or not.”

Romero was a guard for LSU from 1974 to 1978, having been recruited in high school by Coleman.

Without much funding and absent from expectations, Coleman encouraged teamwork and discipline while maintaining high expectations for her players.

Described as hard-nosed, driven and tough, what she demanded of players often led to substantial overturns year after year.

“Lots of running stadiums. There was some punishment there,” Romero said. “Kind of molding a group, a team concept. It was a hard job.”

Players underwent both weight training and all kinds of conditioning, from stadium steps to suicides.

“Just normal stuff, you know. We’d vomit at the end, come back and do it again,” Romero said.

Nancy French played guard under Coleman from 1976 to 79. She recalls enduring a two-and-a-half-hour practice before Coleman decided it was unsatisfactory and ran the entire thing through again. The practice lasted five hours.

Romero started every game of her college career but one. In front of her friends and family at a match in North Louisiana, Romero began the game on the bench because she missed curfew the night before.

While the players embraced the team’s high expectations, few came back for more.

“I think we started off with 13 girls. I think there were only three that came back the next year,” Romero said. “A lot of them finished their first year, but a lot of them did not come back.”

But Coleman wasn’t just a tough-minded coach. Forwards Julie Gross and Maree Jackson came to LSU from Australia. Coleman played a vital role in their lives as they were across the globe from their family.

“She really took care of Maree and I because we didn’t have anyone to turn to,” Gross said. “She kind of became our caretaker, if you want to call it that. If we were sick, she would handle it. Things like that.”

Coming off the inception of Title IX, the women’s team was afforded few of the luxuries the male athletes received.

“I definitely think girls should be offered the same facilities as men,” Romero said in a Jan. 31, 1975 issue of the Reveille. “And I feel our financial situation should be the same.”

In 1975, the women’s basketball allotted budget was $2,200, according to a Reveille issue.

A January 1979 Reveille article detailed a time the women’s team was nearly forced to end their game early in anticipation of a men’s game. Of note, this was against Tennessee, the No. 4 ranked team in the country.

“I don’t consider my team second rate and the game we played was just as important to us as the men’s game was to them,” Coleman was quoted as saying.

Objection from Coleman and the eventual intervention of then Athletic Director Paul Dietzel prevented this. LSU went on to come back from down eight with two minutes left to win 85-80 in overtime.

“The men’s games are scheduled a year in advance and then the women come in here and decide all of a sudden that they are going to have a game,” then-Sports Information Director Paul Mannasseh said. “People don’t come to see women play, they want to see the men and that’s the way it is.”

Men were given priority for practices on the floor. They also received class prioritization, had food specifically prepared for them and had dorms specifically for athletes.

For the first month of her freshman year, Romero stayed in a dorm library converted into a six-person room with three bunk beds.

“Our dressing facilities were pretty much a closet,” Romero said. “I mean, it was nothing.”

Before they started to find success and gain attendees from playing right before the men’s team, women’s players would try to invite classmates to attend their games. At the program’s inception, the bleachers were nearly empty.

The team would pile in a 12-seat van for away games with Coleman in the driver’s seat. They were allowed to travel by plane for select games.

Half the team would fly with the men in the “Flying Tiger,” a “rickety” propeller plane. The others got in a smaller six-seater.

“I always sat in the copilot seat because I didn’t trust anybody else to land the plane if the pilot passed out,” French said.

On short flights to opposing campuses, French was occasionally asked to assume responsibilities outside her job description. She had no aviation experience.

“He would say, ‘Why don’t you fly for a while?’ So I would say ‘Okay,'” French said.

The Ben-Gals went 17-14 in their first season, not making it past the regional round.

The following season, they took a giant leap, going 29-8 and winning their way to the AIAW national championship game.

“We played a really fast game. We liked to fast break,” Gross said. “Our guards were really fast, so we pushed the ball up.”

An offensive strategy reminiscent of the 2025 team did not work for LSU in the 1977 championship against Delta State.

Without their starting point guard and challenged by national phenom Lucy Harris, LSU lost 68-55.

The subsequent year, the Ben-Gals looked even better than their second-place season, commanding a 37-3 record.

After beating them multiple times in the regular season, Stephen F. Austin eliminated them from national contention in the regional round. Ironically, future LSU coach Sue Gunter was the head coach of the team that ended its title hopes.

Gunter coached 22 seasons for LSU beginning in 1982. She made the Elite Eight twice and the Final Four in her last season as coach. She was named SEC Coach of the Year twice and enshrined in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2000.

Despite this, LSU women’s basketball didn’t win its first-ever national championship until 2023, with Kim Mulkey at the helm.

Today, Romero resides in Mangham, Louisiana, and maintains a relationship with Mulkey.

After Romero lost her daughter in 2021, Mulkey sent a letter to Romero expressing her sympathies and offering to talk. Mulkey lost her granddaughter in 2017.

“I think she really cares about people. There’s a lot to Kim that a lot of people don’t see,” Romero said. “She has a big heart. If I called and asked her for something, I think she would either do it herself or see that it got done for me.”

The team Romero played for paved the way for the one Mulkey coaches now. In 50 years, the women’s program has graduated from dancing around .500 and drawing no fans to national champions with a national fanbase.

“I go to watch the girls play now,” Romero said. “I don’t even know if I could be a water girl.”

The status of the LSU brand today and its embrace of women’s sports has the program pioneering a new era of women’s sports just like it did 50 years ago.

“Girls are so much more aware of what’s available for them to work towards as young kids,” Romero said. “They see LSU on the TV. They see programs like that where everyone wants to be a Tiger.”