HUNTSVILLE, Ala. (AP) — A vintage rocket engine built to blast the first U.S. lunar mission into Earth’s orbit more than 40 years ago is again rumbling across the Southern landscape.

The engine, known to NASA engineers as No. F-6049, was supposed to help propel Apollo 11 into orbit in 1969, when NASA sent Neil Armstrong and two other astronauts to the moon for the first time. The flight went off without a hitch, but no thanks to the engine — it was grounded because of a glitch during a test in Mississippi and later sent to the Smithsonian Institution, where it sat for years.

Now, young engineers who weren’t even born when Armstrong took his one small step are using the bell-shaped motor in tests to determine if technology from Apollo’s reliable Saturn V design can be improved for the next generation of U.S. missions back to the moon and beyond by the 2020s.

They’re learning to work with technical systems and propellants not used since before the start of the space shuttle program, which first launched in 1981.

Nick Case, 27, and other engineers at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center on Thursday completed a series of 11 test-firings of the F-6049’s gas generator, a jet-like rocket which produces 30,000 pounds of thrust and was used as a starter for the engine. They are trying to see whether a second-generation version of the Apollo engine could produce even more thrust and be operated with a throttle for deep-space exploration.

There are no plans to send the old engine into space, but it could become a template for a new generation of motors incorporating parts of its design.

In NASA-speak, the old 18-foot-tall motor is called an F-1 engine. During moon missions, five of them were arranged at the base of the 363-foot-tall Saturn V system and fired together to power the rocket off the ground toward Earth orbit.

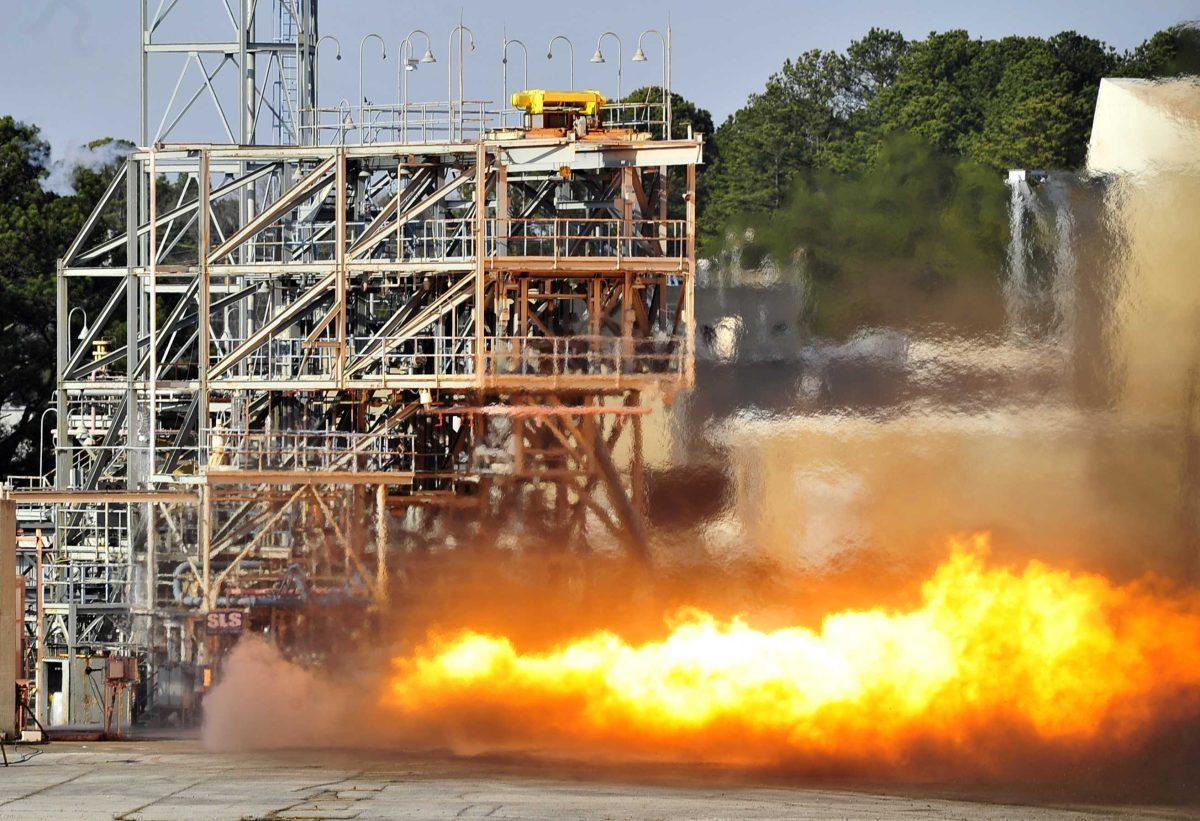

Thursday’s test used one part of the engine, the gas generator, which powers the machinery to pump propellant into the main rocket chamber. It doesn’t produce the massive orange flame or clouds of smoke like that of a whole F-1, but the sound was deafening as engineers fired the mechanism in an outdoor test stand on a cool, sunny afternoon.

The device produced a plume that resembled a blow torch the size of two buses and set fire to a grassy area, which was quickly extinguished.

“It’s not small,” Case said. “It’s pretty beefy on its own.”

And just like during the Apollo days, people in north Alabama heard rockets thundering in the distance during tests at Marshall.

“My wife and daughter were in our front yard and she said they could hear it, which was pretty cool,” Case said after an earlier test. “We live about 15 miles away.”

A single F-1 engine can produce 1.5 million pounds of thrust using a fuel composed of liquid oxygen and refined kerosene, which was not used in the space shuttle.

The tests were conducted at Marshall in a project conducted with Dynetics Inc. and Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne, which are studying NASA’s possibilities for deep-space missions years from now. The space agency plans to use commercial launches to reach low Earth orbit; larger rockets are required to escape the planet’s gravity.

R.H. Coates, an engineer who works with Case in Marshall’s liquid propulsion office, said young engineers can learn a lot from the work done by predecessors using slide-rules in the 1960s, but no one wants to simply rebuild the old Saturn V engine.

“This wouldn’t be your daddy’s F-1,” Coates said. “We’d use new materials and try to simplify it, update it.”

Case started at Marshall as a high school intern in 2002 and has been working there since graduating from the University of Alabama in Huntsville in 2008. He said today’s technology allows things that weren’t possible during the 1960s, but he has been impressed by what he learned taking apart the unused Apollo 11 engine.

Engine No. F-6049 didn’t fit properly on the Apollo 11 rocket, but it is invaluable now as a testing tool. Coates said a total of 85 F-1 engines were used on 17 Apollo flights without a single failure.

About a dozen F-1 engines remain in Huntsville, home of NASA’s main propulsion center, and others are located elsewhere. Most are on display; Case said engineers used engine No. F-6049 for the tests because it was the most complete.

“It is really an excellent booster,” he said. “The guys in Apollo had it right.”