Eight-year-old Shanderrick Williams woke up at 2 a.m. in a Baton Rouge drug house to begin his drowsy search for the bathroom, only to find a buck-eyed being with crazed hair looking in the bathroom mirror. Williams screamed and woke up everyone in the house as he ran away from the beastly-looking figure. A woman caught up with him and covered his mouth with a firm grip, reassuring him, “It is me, your mother.”

“My mom had no job, she had no income and she was addicted to drugs,” Williams said. “We roamed the streets because of her drug addiction. Many nights we went without a stable home and meals, but being together was more important to me than having the luxuries of life.”

Williams said he gained a sense of clarity after that encounter. Before, Williams never let the family jokes about his mother’s drug abuse sway him. Now, he knew the reason for the used needles on the ground, the inconsistency of their nightlife and the aimless walks through the Glen Oaks neighborhood of Baton Rouge. Williams, his younger brother Josh, and their mother would walk for hours at a time each day. After the exhaustion set in, they searched for shelter late at night as his mother sang at the top of her lungs. He trembled at the thought of one of his classmates hearing her and discovering they did not have a home.

“I used to go to the park every single day of my life because I had no where to go, not because it was the place to be,” Williams said.

He found himself on the basketball court with trash-talking men who challenged him to shoot for a dollar. He used his winnings to purchase meals at the corner store for Josh and himself.

After leaving the basketball court, they knocked on door after door in search of their mother. One night, after an unsuccessful hunt, they were forced to return to the park when they were refused shelter because of their mother’s theft the previous week. Josh cried in confusion, asking his older brother where they would go and what they would do. Williams comforted him, saying, “everything is going to be all right.”

That was not to be the case. One day after walking back from Glen Oaks Park Elementary, Williams arrived at the house where they were staying to see 10 police officers surrounding his mother who yelled at them aggressively in the driveway. An officer put her face to the concrete, and Williams witnessed his first arrest. His mother was hauled off to East Baton Rouge Prison for shoplifting at Walmart.

Williams was 9 years old when his mother was arrested for the second time. She was given a three-year sentence in an out-of-state prison. He only saw and spoke to his mother a handful of times. During the few phone conversations he had with her, he was given an automated 30-second warning. Before he had the chance to say “goodbye,” or even, “I love you,” the sound of a dial tone sank into his eardrums.

“I remember me hanging on and holding the phone for seconds after she had hung up to fill that void, to feel her presence and to feel her love,” Williams said.

Things changed for Williams after he and Josh moved in with their grandparents. His grandmother instilled values in his life. She taught him about God and how to protect a home. She also enrolled him in the Young Leaders Academy, an organization in Baton Rouge that nurtures young African American men to develop leadership abilities and help them become productive citizens. He formed relationships with role models who instructed him to speak boldly. Williams now had the opportunity to pursue the great things he was meant for. He never doubted his ability, even when his third grade teacher told him she would see his face on the front page of The Advocate one day for a crime. In the sixth grade, he did not hesitate to visit her and boast the report card that gave him honor roll status.

“I understood that my whole life, I was getting two educations; I was getting the street education and I was also getting the academic education,” Williams said.

Growing up in a rough neighborhood, he learned hustles, and he said he believes entrepreneurship is similar to hustling someone or something. He said being book smart means understanding how to make deals legitimate. Williams combined the two when he established his own publishing company and became an author in 2012 while majoring in communication studies at LSU.

Williams recalled waking up after a dream at 2 a.m. once again — this time at Herget Hall during his freshman year. He began to research the publishing industry with the intention to publish a book through his own company.

“Every day of my life began to be about the publishing industry,” he said.

That dream birthed his book, “The Lost Power, “ in which Williams unveils intimate details about his life to the world in hopes of inspiring this generation to embrace their situation and fearlessly move toward their aspirations. His book is his testimony and a source of encouragement for others to achieve greatness and pursue their dreams no matter their personal background, ethnicity or financial status.

Williams and former LSU defensive tackle Anthony Johnson founded Generation X Club in 2013. The two first met when Johnson chose Williams to be on his basketball team at the UREC. Johnson then connected with Williams on Twitter.

“Something was instilled in him that I had never seen before,” Johnson said. “You know what I mean? I just knew he was special.”

The foundation’s slogan, “We do the impossible,” is carried to crime and drug-affected areas where Williams visits and spreads his message to young adults. Having similar childhoods, Williams and Johnson formed a bond through their shared vision of helping impoverished youth to reach their full potential.

“My entire life, I had this unshakable desire to be great,” Williams said. “I say unshakable because I was bouncing around my entire life and what I experienced — the adversity, the hardships — shook me away from greatness. And to me, greatness was being a servant and always smiling through whatever.”

Lost & Found

By Raina LaCaze

February 17, 2014

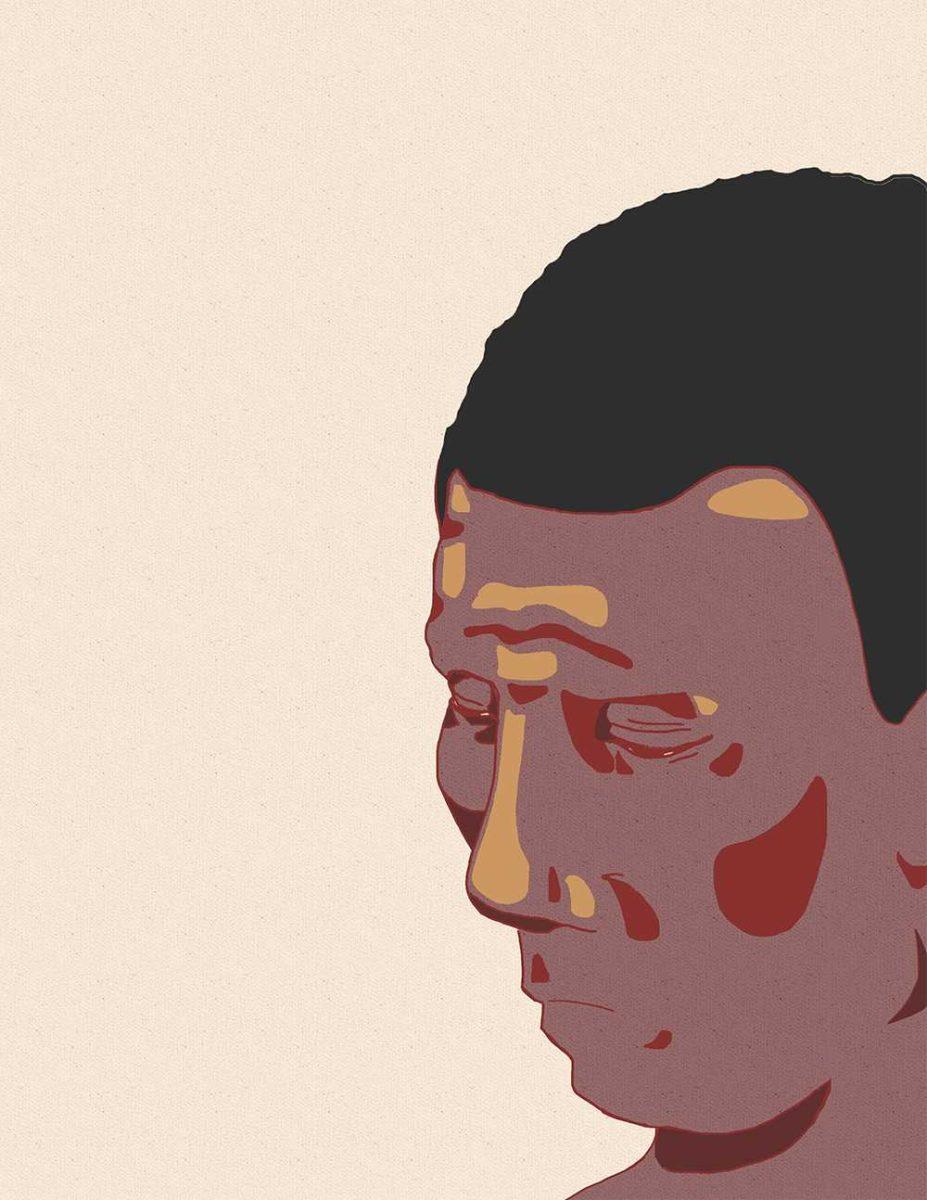

Shanderrick Williams revisits the park where he and his brother, Josh, played basketball as children.