At 4 a.m. on a Tuesday morning, a group of graduate students begin their route through Peru equipped with bin- oculars, a field guide of Peruvian birds, cameras with long-focused lenses, and a collection of audio recordings.

The group seeks to break Parker’s record.

They call themselves the Tigrisomas, LSU’s bird watching team. The name derives from the genus name for the tiger heron, a native bird found around the LSU lakes whose feathers resemble the pattern of a tiger’s coat.

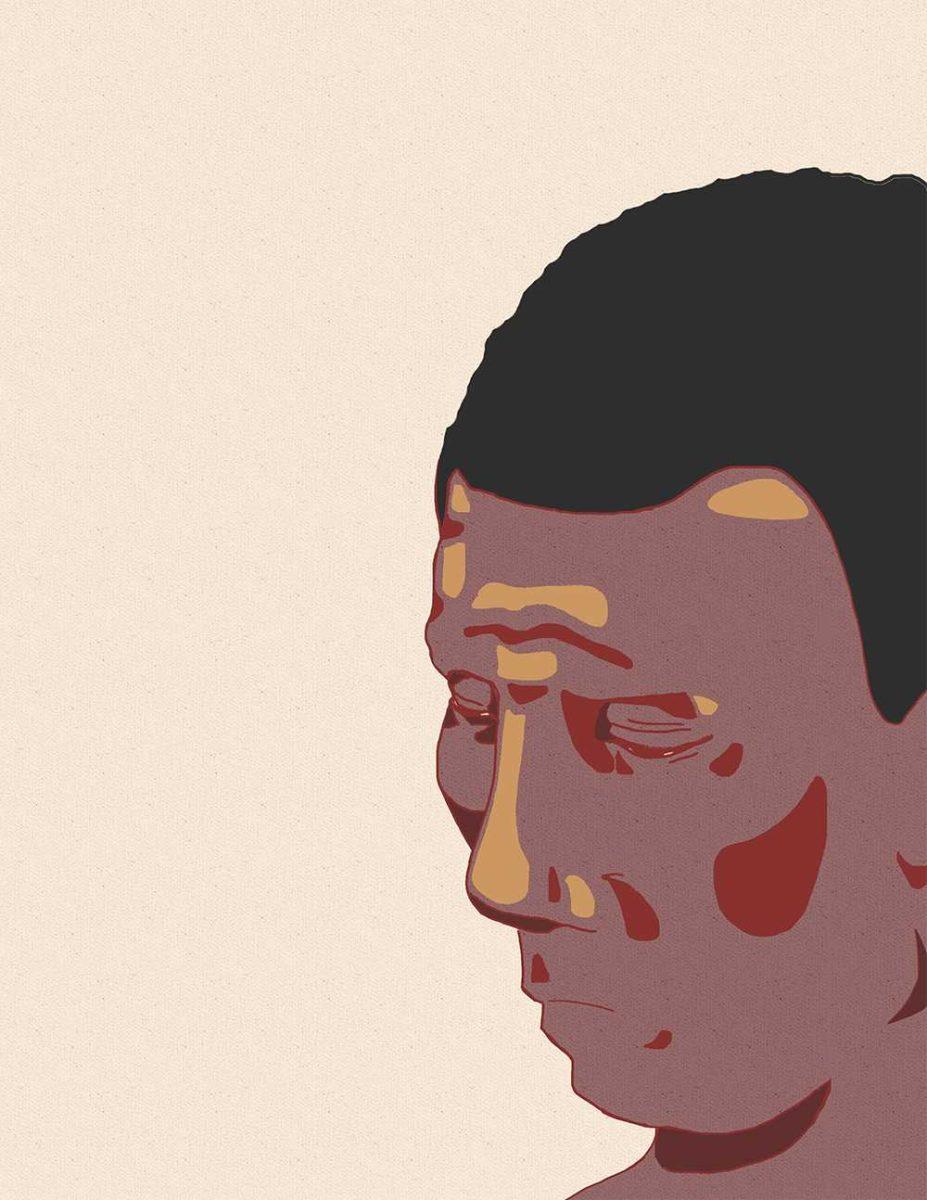

The team comprises of LSU grad students Michael Harvey and Glenn See- holzer, LSU Museum of Natural Science Research Associate Dan Lane, and re- search assistant and Peru native Fernando Angula.

Working on little sleep, the Tigrisomas continually cupped their ears in search of familiar bird songs they learned from over 10 years of study in South America. Hear- ing birds is faster than spotting them.

Harvey and Seeholzer agree that iden- tifying birds by sound comes relatively easy to them – almost like muscle memory.

“It’s like recognizing a family mem- ber’s face from yards away, except it’s a bird,” Seeholzer says. “Though birds are pretty much family at this point.”

Harvey and Seeholzer are not Loui- siana natives, but their passion for birds along with stories of Ted Parker drew them to LSU. The pair have long waited for an opportunity like Big Day Peru to arise.

With the help of their advisor, direc- tor of the LSU Museum of Natural Sci- ence Robb Brumfield, the group managed to raise enough money for the trip through fundraisers and research grants.

Currently, LSU does not sponsor the Tigrisomas, making them an independently funded organization.

The team continued through Peru, enduring harsh weather conditions like heavy rain.

“I just had so much adrenaline and Redbull running through my system then,” Harvey says.

Harvey’s fascination with the birds pushed him to keep going.

Finally, at 9:45 p.m., the team spots their last species, an oilbird, but the record remained uncertain.

“We’re moving so fast that we don’t have time to count,” Seeholzer says. “We couldn’t be sure we were breaking the re- cord.”

After a tally, the Tigrisomas succeeded in breaking the world record by identifying 354 species.

But who keeps the team in check when the sporting activity involves no referees or overseers?

The activity mainly relies on the honor system.

Despite being unregulated, the team collected various sound bites and photos to prove their victory.

However, Brumfield was elated when he heard the news, but he was skeptical.

“The record hadn’t been broken since 1982,” Brumfield said. “For LSU, I think it’s a nice feather in the hat.”