If you watched news coverage of the protests in Ferguson, Mo. after a white police officer shot a young, unarmed African American, then you probably took sides: either with the people of Ferguson or with the police.

Regardless of your position on this issue, it is undeniable that this dichotomy of the “white” group versus the “black” group distorts the important questions that the incident in Ferguson brings up such as racism, police militarization, pluralism, etc. Furthermore, it dangerously furthers the racial divide between ethnic communities in our country, rather than mediating those differences to form a peaceful coexistence that all citizens can enjoy, whatever their skin color.

This phenomenon of racializing deracialization—that is to say, reading race into a discourse about transcending race—is backward progress that only seems helpful because race factors into the equation.

But it hinders racial progress by pitting ethnic communities against each other.

Take, for example, a typical response from the “white” camp.

He then goes on to cite high school drop-out rates, unemployment and out-of-wedlock births as causes of this behavior.

Without proper acknowledgment this rhetoric becomes ammunition for certain readers to shoot the burden of guilt at the black community, absolving themselves of sin.

I’m not suggesting Williams should censor these types of comments; on the contrary, these are important elements of the racial problems that deserve to be discussed. But there must be an acknowledgment of the different sources of these problems: a disproportionate educational system, a shortage of proper role models or leaders for young black men and women, and an imbalanced penal system, among others.

More importantly, however, is what does not need to be in these articles and people’s opinions across the country.

There should not be a sweeping accusation of guilt for such a deep, complex topic as race aimed against a single ethnic community as if it were a monolithic consciousness without diversity of opinion. Not only are these accusations patently false and untrue to the intricacies of the problem, but they also stoke the fires of hate and intolerance among communities by throwing guilt around like a hot potato.

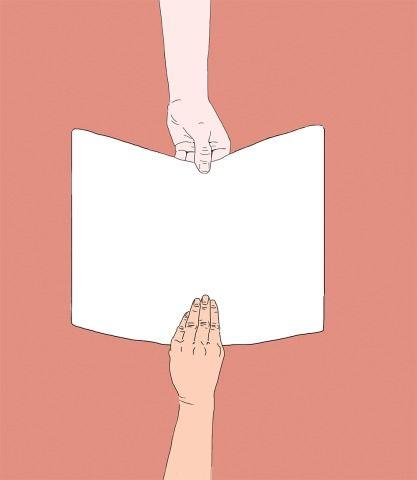

If our generation is serious about equality, about judging people not by the color of their skin, then we must be willing to see justice or injustice, freedom or oppression, not black or white, male or female.

Certainly in situations like Ferguson race can still matter as a potential target for discrimination, without determining anything about an individual. White cops are not necessarily evil by virtue of their whiteness, but, if they are evil, it is because of their brutality—a quality certainly not dependent upon race.

And by the same logic, young black men are not guilty by virtue of their blackness. If we want true progress, then character must always trump race.