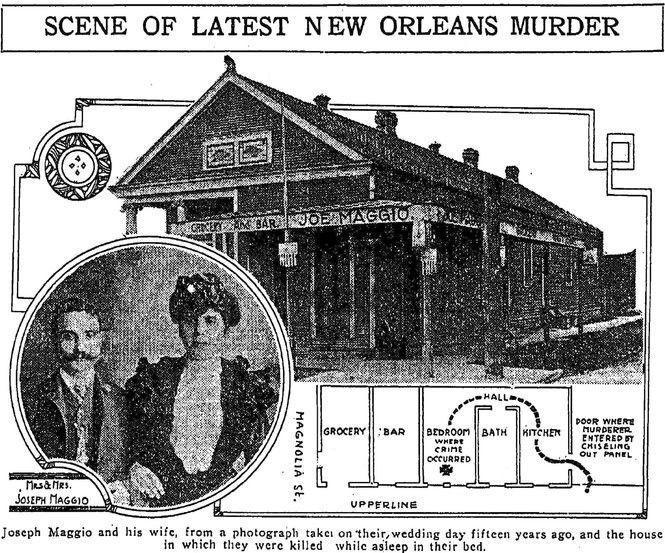

On May 23, 1918, Andrew Maggio celebrated his acceptance into the navy with a night of drinking in New Orleans. Stumbling home drunk, he heard strange groans coming from the apartment next door at Upperline and Magnolia streets. In that apartment lived his brother, Joseph Maggio, and his sister-in-law, Catherine Maggio, who were lying still with their throats slit and theirs heads bashed in with an axe.

Joseph, an Italian grocer, was still alive when Andrew found him but died minutes later. Catherine’s throat was cut so severely that her head was nearly off her shoulders. A bloody razor belonging to Andrew’s barbershop was the primary murder weapon. Questioning how Andrew couldn’t hear the forced entry of a crazed axe murderer, the police arrested Andrew Maggio as the primary suspect of the murder of the Italian couple. However, police soon found out that Andrew was not the murderer. Instead, they attributed this killing to the man who would soon terrorize Louisiana, the Axeman of New Orleans.

Horrifying accounts of brutal murders would soon become a regular occurrence for New Orleans citizens in 1918 and 1919. The murders all played out in similar fashion. Door panels were chiseled out of entrances, through which a reportedly large man would access the lock and enter. Wielding an axe belonging to the residents, the man would swing at his victims while they were sleeping. The homes were ransacked, but items were rarely taken. The survivors were often unable to describe what happened. The police were dumbfounded and unable to find substantial leads.

The victims were typically Italian grocers. By this time in New Orleans, Italians owned about half of the groceries. Immigrating to America in large swaths, they were targets of xenophobia by the dominant Anglo-Saxon class who viewed them as criminals and con artists of an inferior race. The Axeman’s primary motive seemed to be his xenophobia towards successful Italian immigrants of New Orleans.

On June 27, 1918, one month after the death of the Maggios, Louis Besumer and his mistress Harriet Lowe were attacked in Besumer’s grocery by a man with an axe. Besumer was struck in the right temple, while Lowe was struck over her left ear. John Zanca, a wagon driver, discovered the two around 7 a.m. lying in a puddle of their own blood. They were alive.

Lowe described the assailant as a “mulatto” man. A 41-year-old African American man named Lewis Oubicon who worked in Besumer’s grocery gave conflicting accounts to the police about his whereabouts. Police arrested him but could not find any evidence linking him to the crime.

Newspapers thought Besumer’s affair with a mistress was scandalous and often reported on his life. Lowe herself played into the media frenzy by making conflicting and taboo statements about the attacks and about Besumer. Lowe died Aug. 5, 1918 following a complication in a surgery to fix her paralysis due to the Axeman’s attacks. However, on her deathbed, she stated that Louis Besumer was the man who attacked her with the axe.

Police had already suspected Besumer, but not for being the Axeman. They found letters in Russian, German and Yiddish, and when asked, Harriet Lowe confirmed that Besumer was a German spy for Kaiser Wilhelm II. However, the police were wrong about Besumer’s role in espionage, and a jury found Besumer not guilty of the assault on Harriet Lowe following a 10-minute deliberation and 9-month arrest.

On August 5, 1918, the same night of Harriet Lowe’s death, Anna Schneider, 28, awoke to a dark figure standing over her bed. The man bashed her head in multiple times, cutting her scalp open with what police believed was a lamp. Her husband, Ed Schneider, returned late from work after midnight to discover Anna with her face covered in blood. Anna was alive but remembered nothing from the attack. 8 months pregnant at the time, Anna gave birth to a baby two days later.

Authorities discovered none of the windows or doors to have been forced open. They arrested an ex-convict named James Gleason who ran from the authorities. There was no evidence connecting him to the crime, so he was released, stating that he only ran because he was often arrested. By this time, police were completely confounded over each case. Having no leads, they publicly speculated that these attacks were by the same man.

Five days later, on Aug. 10, 1918, Pauline and Mary Bruno awoke to find their elderly uncle, Joseph Romano, in his room with two cuts on his head. As they entered, a dark-skinned, heavy-set man wearing a dark suit and a slouched hat was fleeing the house. Romano died two days later. The cops found a bloody hatchet in the backyard and a chiseled back door panel.

Following the Romano murder, New Orleans was in full paranoia. People called in to police, claiming to find axes in their backyards and seeing an axeman lurking around their area. A retired detective, John Dantonio, added to this chaotic atmosphere with public theories published in The Times-Picayune.

Dantonio hypothesized that the killer had dual personalities. One of a normal citizen and the other of a man with an insatiable lust for murder who killed without motive; a real-life “Dr, Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Dantonio connected the 1918 murders to a series of similar cleaver assaults elsewhere in Louisiana from 1910-1912. In the Maggio couple murder, detectives found a message in chalk which read “Mrs. Maggio is going to sit up tonight just like Mrs. Toney.” Mrs. Tony Sciambra was apparently an Italian woman who was shot and killed in 1912.

On March 10, 1919, the Axeman traveled across the Mississippi to nearby Gretna at Jefferson Ave. and Second Street. Grocer Iorlando Jordano, 69, heard screams coming from his neighbors, the Cortimiglias. There, he found Charles Cortimiglia lying on the floor bleeding, and his wife, Rosie, clutching her dead infant daughter, Mary, while bleeding from a head wound.. A bloody axe was found, and a back door panel was removed.

Rosie claimed that Iorlando and his son, Frank Jordano, attacked them. Iorlando was too frail to have assaulted them, and Frank was too large to fit through the door panel. Despite that, police arrested them, and they were found guilty. Frank was to be hanged, and Iorlando was sentenced to life in prison. Charles Cortimiglia, however, denied his wife’s claims and eventually divorced her after the Jordano trial. Rosie later said she falsely accused the Jordanos out of jealousy and spite. They were released from prison.

Three days later, on March 13, 1919, the Axeman wrote a letter to the media signed from Hell.

“Esteemed Mortal:” the Axeman wrote. “They have never caught me and they never will. They have never seen me, for I am invisible, even as the ether that surrounds your earth. I am not a human being, but a spirit and a demon from the hottest hell. I am what you Orleanians and your foolish police call the Axeman.”

He continued to talk about his Satanic abilities throughout the letter, and towards the end, issued a funky threat. If a house plays jazz on March 18, 1919, those people will be spared from his axe. Anyone who doesn’t “jazz it” at 12:15 a.m. “earthly time” would be under threat of his demonic brutality.

Legends recount that March 18 was the loudest night in New Orleans history. Jazz clubs were filled with paranoid Orleanians, and households blared jazz through their phonograms. No one died that night. A local jazz musician named Joseph John Davilla even wrote a song to scare off the Axeman, titled “The Mysterious Axman’s Jazz (Don’t Scare Me Papa).” The song was a hit and made Davilla lots of cash, leading to theories that Davilla himself wrote the Satanic letter to boost jazz’s popularity.

Two similar attacks happened on Aug. 10 and Sept. 3, 1919. Steve Boca and Sarah Laumann awoke to an axeman attacking them. Both survived their attacks and were unable to recall what happened.

The last of the alleged Axeman attacks happened Oct. 27, 1919. Esther Pepitone awoke to her husband, Mike Pepitone, being struck in the head by a large axeman. Blood splattered all over the room, but Esther couldn’t describe the killer.

Esther relocated to Los Angeles where she married a man named Angelo Albano. On the second anniversary of Mike Pepitone’s death, Albano mysteriously disappeared. Albano used to have business relations with a man who went by Joseph Mumfre. Mumfre visited Esther’s home on Dec. 5, 1921, where he demanded $500 and jewelry. If Esther refused, Mumfre would “kill her the same way he had killed her husband.” Esther, however, got a revolver and shot him dead.

When the police came, Esther claimed that she saw that same man the night Mike Pepitone was murdered. The police found circumstantial evidence linking Mumfre to Pepitone’s murder, including Mumfre’s leadership role in a blackmailing gang in New Orleans targeting Italians. Adding to the likelihood of Mumfre being the Axeman is the earlier 1912 shooting of the Sciambras. The prime suspect, in that case, had the name ‘Momfre,’ and Joseph Mumfre was known to go by multiple names.

Despite this, experts still disagree on Mumfre’s guilt since no substantial evidence linking Mumfre to the axe killings was found. The murder of Mike Pepitone and the Sciambras could be attributed to Italian gang violence, and whether Pepitone was killed with an axe is disputed. Many theories abound about who the Axeman was or what happened to him later. Evidence from police records and newspapers show that he may have reappeared in Louisiana sometime later. Alexandria, DeRidder and Lake Charles all had Italian grocers fall victim to axe attacks. However, after that, the Axeman completely vanishes. The secret identity of the jazz-loving, Italy-hating Axeman of New Orleans will likely stay a mystery forever.