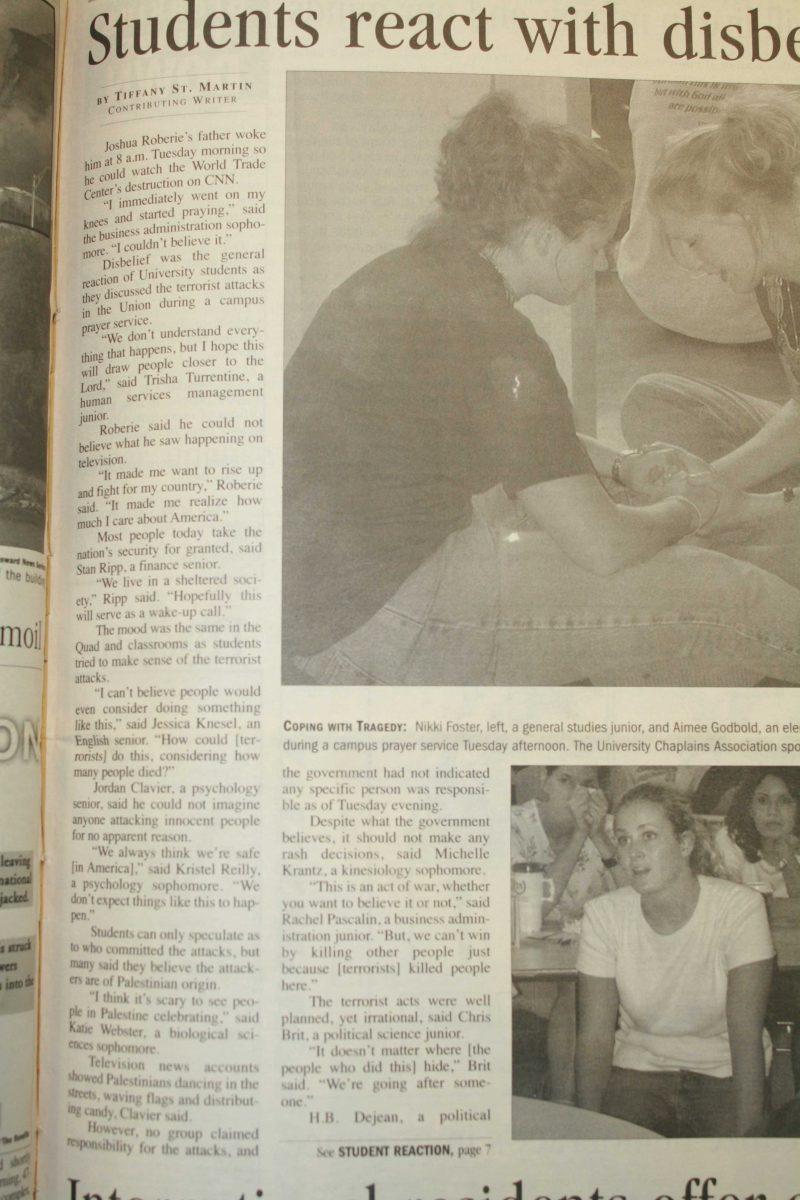

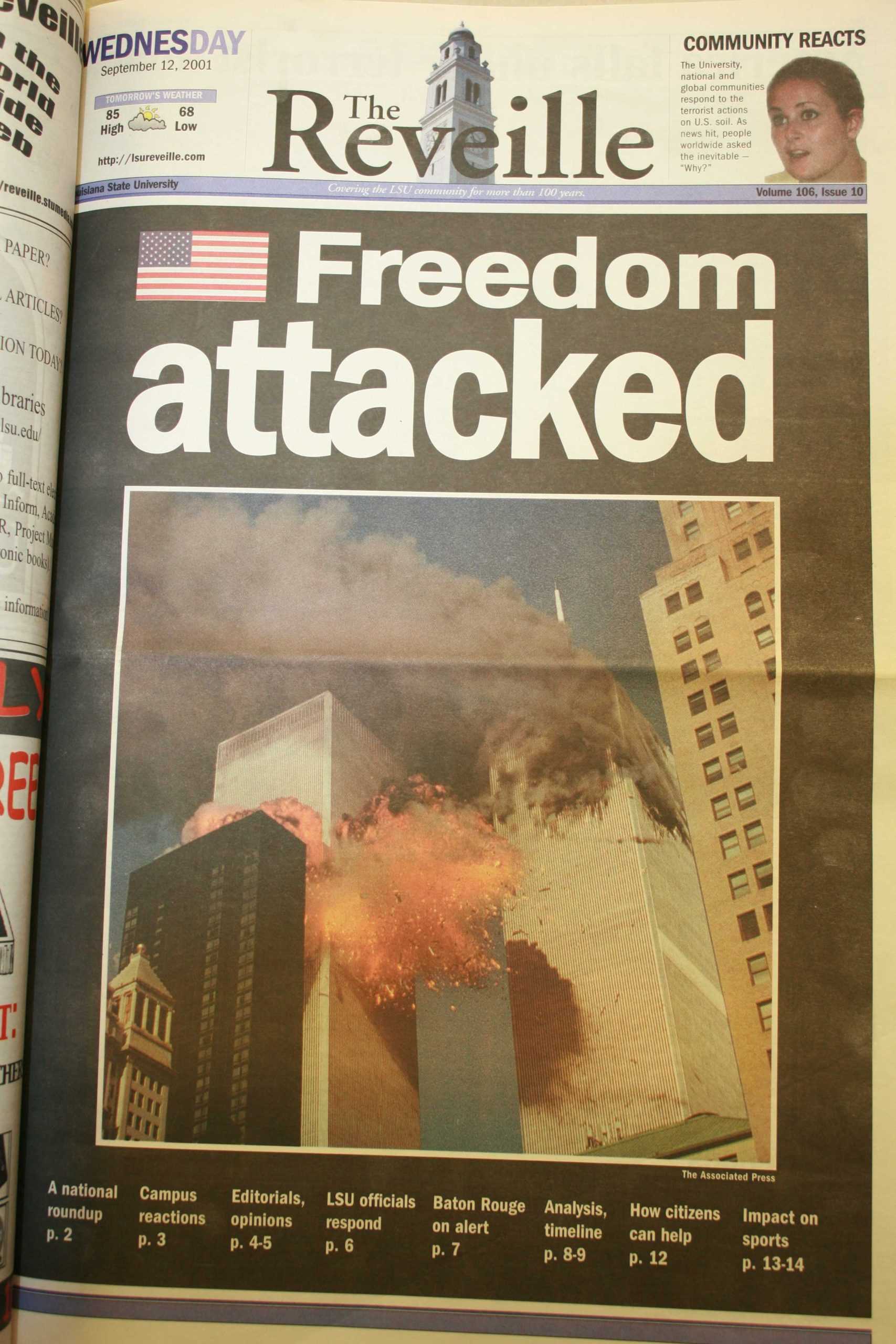

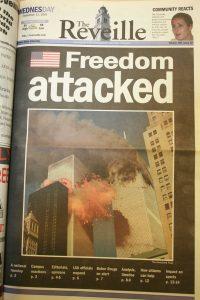

On Sept. 12, 2001, LSU students reacted in disbelief to the attacks on the World Trade Center a day earlier.

“Disbelief was the general reaction of university students as they discussed the terrorist attacks in the Union during a campus prayer service,” as reported by The Reveille.

Almost 60 years prior, when Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japanese forces on Dec. 7, 1941, students felt similar attitudes on the eve of war. In a letter to the editor in the Dec. 9 issue, Mary Carolyn Bennett felt the winds of change in the wake of the attack.

Bennett wrote the letter following an event on the night of Dec. 7, where 2,000 students gathered, screaming “go to hell Tokyo, go to hell” and sang “God Bless America.”

“All felt in some way that Sunday night was the last carefree night for an eternity. Sunday night was the end of this generation’s world,” she wrote. “Sunday night was the last day everyone was simply a college student… Many will die in this war but they had one last get together, Sunday night was theirs.”

Now, in 2022, LSU international students from Ukraine have reacted to the invasion of their homeland by their Russian neighbors.

According to the United Nations, confirmed Ukrainian civilian casualties have approached 1,800 dead, with nearly 2,500 injured since Russia invaded the country on Feb. 24.

Danylo Zaitsev, freshman biology student from Ukraine, along with other Ukrainian students have spent the past few weeks holding signs and waving the blue and yellow Ukrainian flag to attract more attention to the conflict, which has garnered international condemnation and heavy sanctions for Russia.

“The first thoughts to many guys, many Ukrainian guys in LSU, was to return back home,” Ukrainian microbiology senior Mykola Koval said.

Koval’s father is serving as an officer for the territorial defense force, a reserve for the Ukrainian army.

Professor of international relations David Sobek said he believes the Soviet-Afghan war to be the closest analogue to the Russo-Ukrainian conflict.

“It’s Russia attacking a neighboring state to impose a puppet regime on it,” Sobek said. “It also goes more poorly for the Russians than they anticipated. I hope this doesn’t last another eight years before the Russians leave.”

The Soviet-Afghan war began when a coalition known as the Mujahideen openly revolted against the Soviet-backed communist government, causing the Soviets to intervene on behalf of Afghanistan’s then-communist leadership, exerting their influence in the region.

Sobek said that much like the Russo-Ukrainian war, a Moscow regime thought their opponents would not provide as much resistance as they did, drawing a clear comparison to the Soviet-Afghan war.

Most sources believe that well over one million Afghan civilians died in the conflict with the Soviets and millions more were displaced, domestically and abroad.

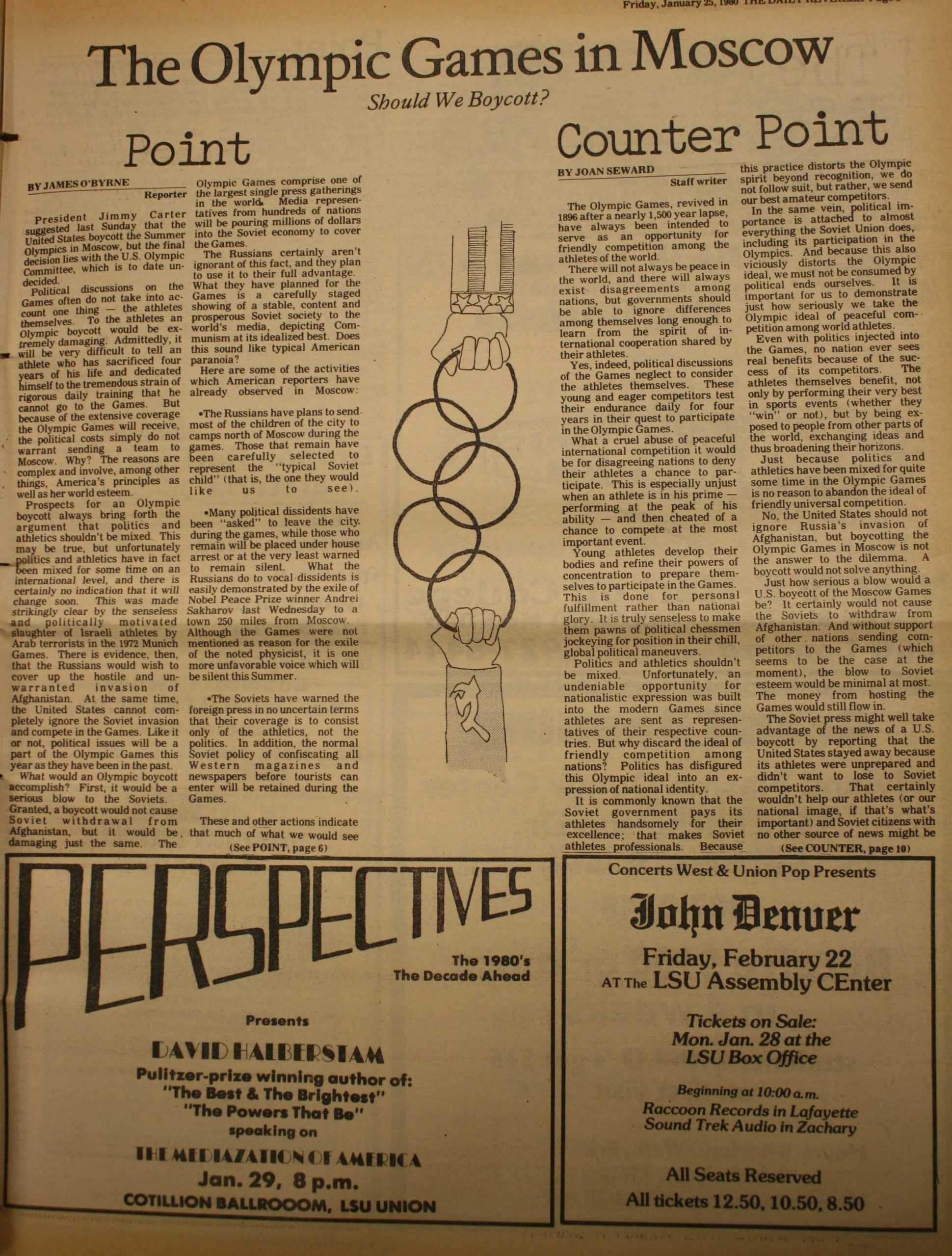

The Jan. 25, 1980 issue of the Reveille featured two dueling opinion columns arguing for and against the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics because of the events of the Soviet-Afghan War.

Former Reveille columnist James O’Byrne advocated the boycott of the games.

“The United States cannot completely ignore the Soviet Invasion and compete in the games. Granted, a boycott will not cause Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, but it would be damaging just the same,” O’Byrne wrote.

O’Byrne’s sentiment argues that reparations need to be amended on the Soviet front and that by isolating them, the U.S. could internationally condemn Soviet actions.

Arguing the counter point is Joan Seward, writing that the games and the politics surrounding them should be treated separately.

“There will not always be peace in the world and there will always exist disagreements among nations, but governments should be able to ignore differences among themselves long enough to learn from the spirit of international cooperation shared by their athletes,” Seward said.

Seward said that “politics and athletics shouldn’t be mixed;” the insistent nature of the nations that chose to not participate in the Olympics may have further isolated themselves from clarity and negotiations.

Those arguments parallel mixed reactions against the United States’ response to the Russian invasion. The U.S. and its allies have imposed heavy sanctions on the Russian economy since the invasion.

Some students, like economics and political science junior Rehm Maham, believe sanctions a justified means to hinder Russian efforts internationally and domestically. To him, sanctions are a form of active condemnation.

“The Russian regime is an ongoing violation of international law,” Maham said. “The Russian people are unfortunately going to have to bear the consequences of having a government in power that is committing war crimes in Ukraine.”

Other students, like international trade and finance sophomore Cooper Fergusson, believe that sanctions aren’t a fair or effective measure against Russia.

“If we look at Iran, Venezuela, Cuba and these other places where U.S. sanctions have been in place in the past, they haven’t done anything except restrict food, medical aid and necessary survival methods.”

Looking back at reporting done by student journalists with the Reveille, patterns begin to form that draw similarities to how the university’s community is responding to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, like how opposing nations are depicted and perceived.

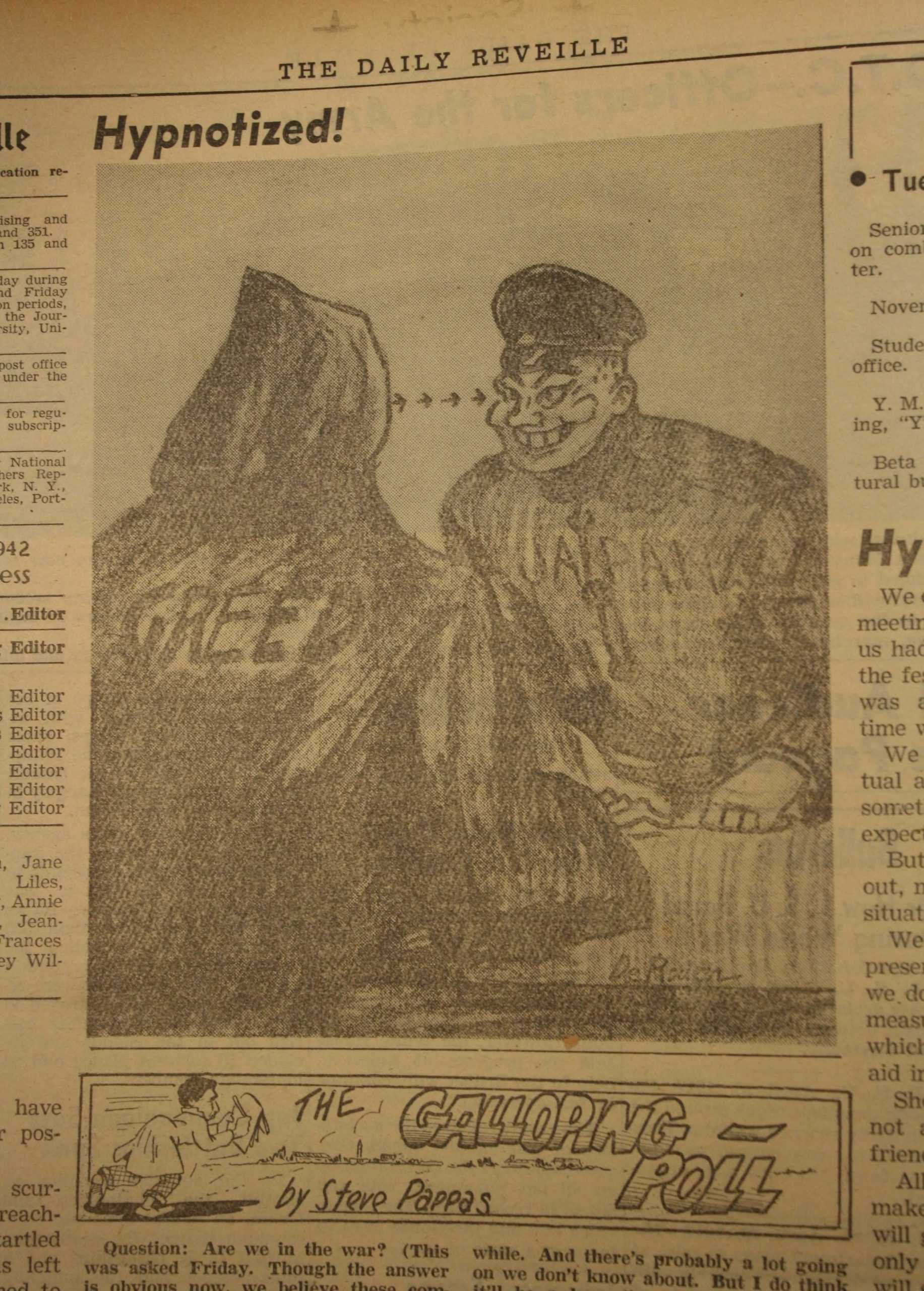

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the Reveille published a political cartoon entitled “Hypnotized!” in its Dec. 9 issue that featured a racial caricature of a Japanese military officer being hypnotized by a cloaked figure depicted as “Greed.”

In the days following 9/11, Muslim students shared experiences of similar treatment on the sole basis of their national origin or religion.

“Local Muslims said they already feared retaliation,” a Reveille article said.

These racist attitudes were not uncommon around the country, especially following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and 9/11.

Zaitesev and other Ukrainian students set up a table in Free Speech Alley in February to inform students about the war. They said LSU students are generally aware about the conflict.

“It can happen anywhere,” he said. “People can really just contribute to this by thinking about it.”