LSU Libraries’ newest exhibition showcases Louisianians’ relationship with natural resources and the potential they have to threaten life and property.

The exhibition, “Water, Water Everywhere: Control and Consequence in Louisiana’s Coastal Wetlands,” will be on display in the Hill Memorial Library through Dec. 21.

Leah Jewett, exhibitions manager for LSU Libraries Special Collections, said the timeline of the displays is from the early 18th century with original European settlements into contemporary times.

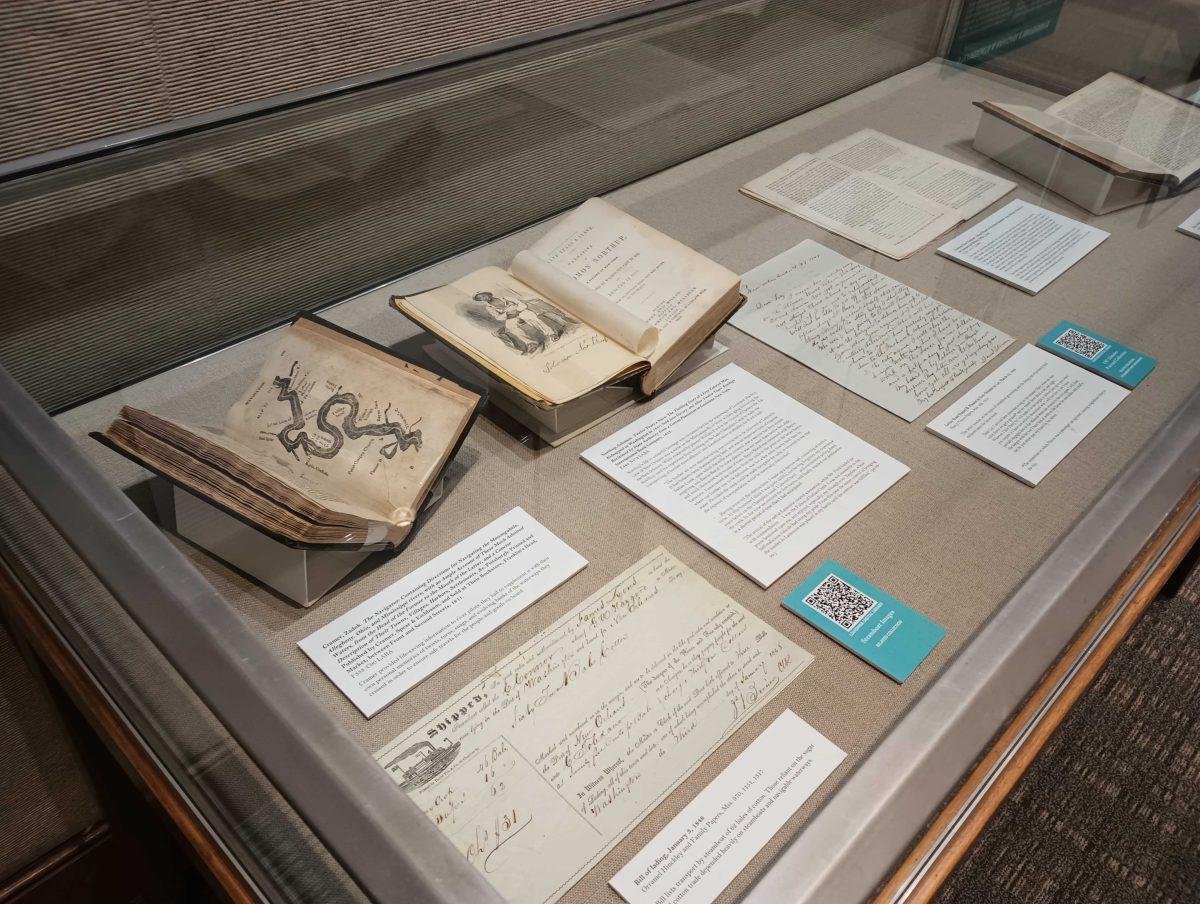

Displays for the exhibition, which started on Sept. 6, include historic photographs of men working on levees, letters describing floods and citizens’ responses to them, and documents promoting various shipping canals.

One of the most notable additions to the exhibition, Jewett said, is a 19th-century piece of sheet music named after a levee break, “The Bell Crevasse Mazurka.”

Jewett said that the issues Louisianians face regarding flooding and coastal wetlands loss due to human activity are long-standing.

“You cannot study Louisiana history without studying our struggles with flooding and our attempts to control waterways,” Jewett said. “The exhibition features items that put in context the human activities that have had an impact on the coastal wetlands but have also benefited Louisianans.

Louisiana’s history with water is complicated, Jewett said. According to Jewett, individuals must study and understand this history because of its importance to the coastal regions and the people who live there.

Jacob Gautreaux, a fifth year Ph.D. student and teaching assistant in the university’s history department, said that the exhibit can reveal some of the reasoning behind the choices of manipulation of water and nature made in Louisiana during the 20th century.

“These choices make Louisiana an exhibit for the rest of the nation to envision a possible future where sacrifice for profit exponentially increases exposure to climate-related risks,” Gautreaux said.

Gautreaux said that he hopes the exhibition itself will motivate change and remind individuals that the larger global impact of man-made climate change starts in the national and local context.

“Not only do our decisions matter as an entire globe and nation, but even more so at a local and individual level,” Gautreaux said.

Exhibits like the one at Hill Memorial Library help to draw in curious-minded students and researchers that may not have the knowledge of the extent at which water has impacted Louisiana.

Gautreaux said that this exhibition creates a chance to interact with past records and traditional cultural knowledge related to water.

“Water is an ever-present feature in Louisiana that I have yet so much to learn about,” Gautreaux said. “The amount of information those in the past have written on, talked about, debated over and actually carried out the manipulation and attempted management of water is beyond the scope of an individual.”

He said that audiences should view the exhibit and ask questions about any display that intrigues their interest.

Civil and environmental engineering senior Madalyn Mouton has worked on projects such as water budget analysis on the Mississippi River, as well as the effectiveness of the dredge sediment in recent marsh creation projects and environmental flow rates in the Atchafalaya, with the Hill Memorial Library exhibition assisting her research into the Mississippi River, the Atchafalaya Basin and coastal Louisiana.

According to Mouton, there are QR codes within the exhibition that link to other LSU Libraries collections, including the “LSU Libraries Louisiana Waterways Management Collection,” “William Barth Photographs of Mississippi and Atchafalaya River Operations” and “Burrwood, Louisiana and Southwest Pass Jetties Constructions Photographs.”

While Mouton’s focus is looking for certain keywords and documentation of data, she said the exhibition inspired her by showing the stories of the people behind these water-related problems.

“The letters, the photos, and even the music show more about how we have interacted with the water over the two centuries we’ve been here,” Mouton said. “This makes [my research] mean something more when understanding the bigger picture of living with water.”

Glassed pictures of flooding and Coastal Wetlands of Louisiana on display in the Hill Memorial Library in Baton Rouge, La.