The vast majority of reports filed to LSU’s Division of Engagement, Civil Rights and Title IX — which deals with issues like sexual assault, dating violence, workplace harassment and other allegations of sex-based discrimination — end without a formal resolution or disciplinary action, according to three years of data reviewed by the Reveille.

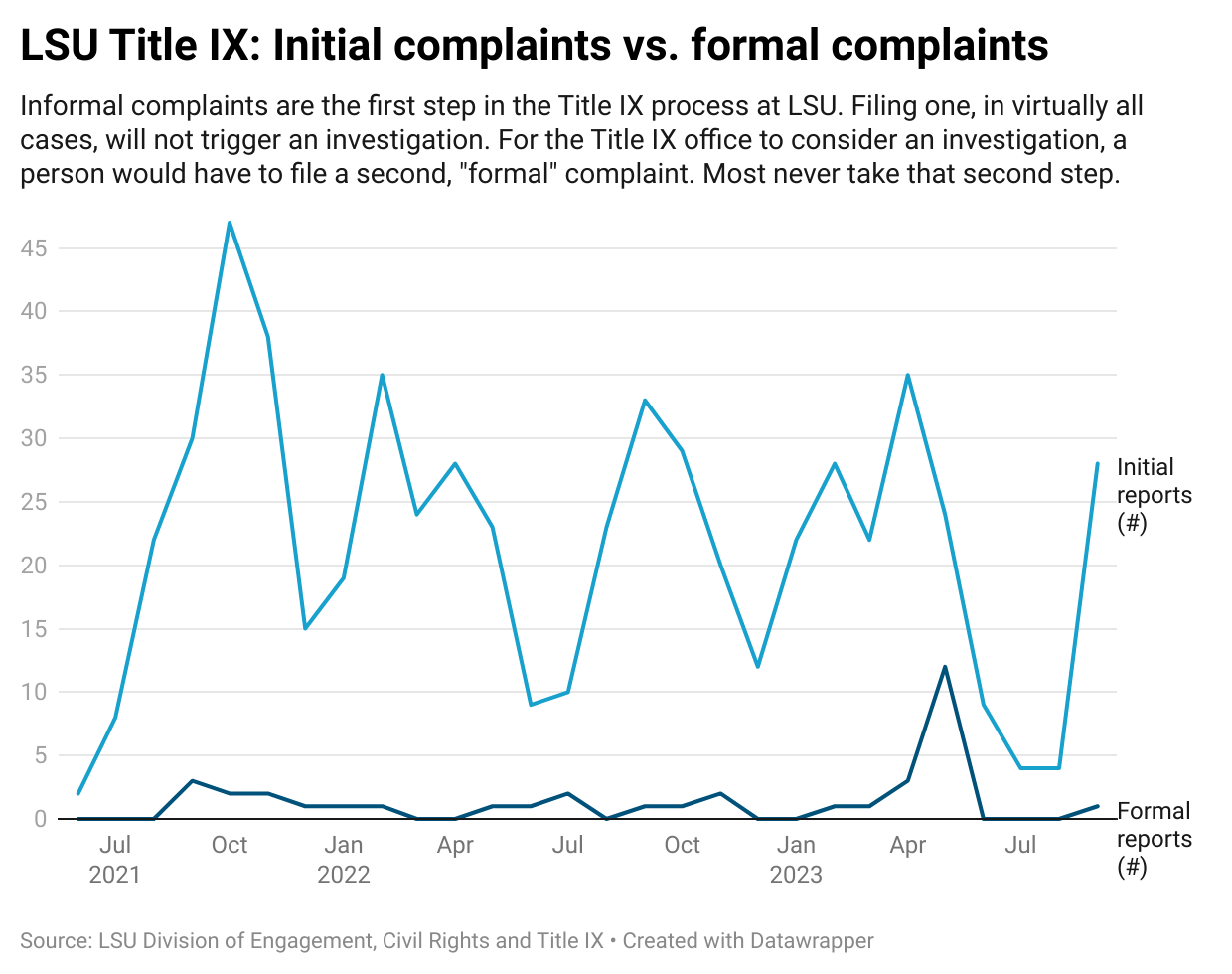

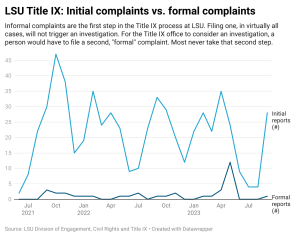

An initial report to the Title IX office doesn’t trigger an investigation in virtually all circumstances. For the Title IX coordinator to consider investigating an alleged violation, a second, “formal” complaint must be submitted to the office.

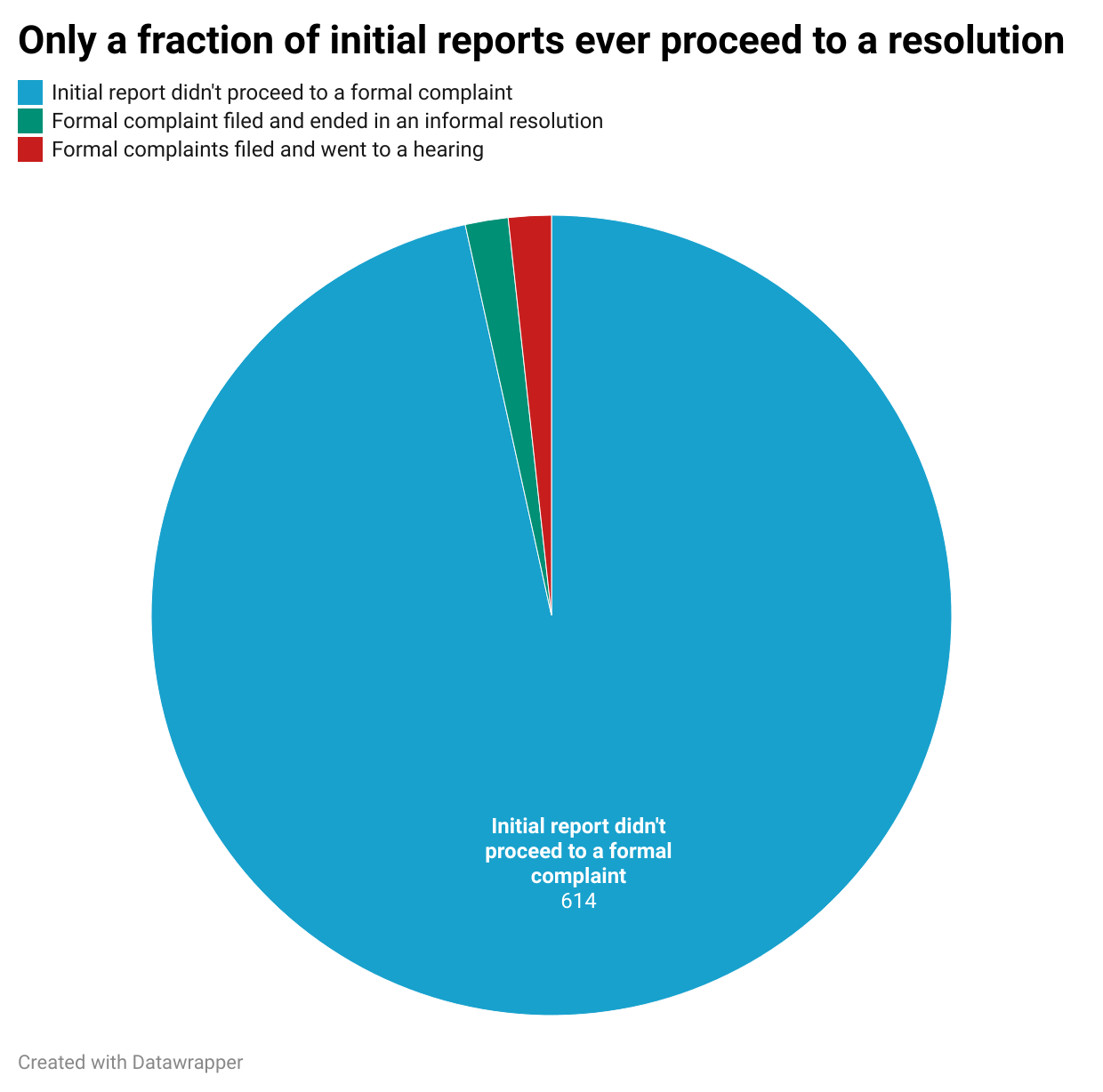

At LSU, less than 1% of initial reports evolved into hearings that ended with the perpetrator being removed from campus, according to a Reveille analysis of the publicly-available data. That’s largely because only 5% of those who first reported to the Title IX office took that second step.

Out of the 636 initial reports filed from June 2021 to September 2023, only 11 evolved into formal complaints that ended in a panel hearing that ruled whether the alleged perpetrator was “responsible” or “not responsible” for the reported violations. That’s less than 2% of total reports.

The investigation period for a formal complaint “can take 45-60 business days, and sometimes longer depending on caseload and academic year timing,” according to the Title IX website. In data from the office, one formal complaint took 158 days to close. Another took only 28.

READ MORE: April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month: Here’s how LSU and Baton Rouge are recognizing it

The Reveille also found LSU’s Title IX office recently used a disciplinary measure that was removed last year from the LSU Code of Student Conduct because of its leniency toward perpetrators of sexual assault.

A 2021 USA Today report found three-of-five students found to have committed a Title IX offense were allowed to continue their work at LSU without interruption because they were issued a “deferred suspension.”

Under a deferred suspension, a student found responsible for sexual assault isn’t removed from campus unless they’re found responsible for another Title IX violation within a designated time period, typically two years.

In January 2023, the LSU’s Division of Student Affairs removed deferred suspension as an outcome for violating the Code of Student Conduct, the Reveille found using the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

But just a few months later, in April 2023, LSU’s Office of Title IX issued a deferred suspension to a defendant found guilty of sexual assault, specifically “forcible fondling,” according to the office’s most recent data.

The Reveille contacted Joshua Jones, LSU’s associate vice president for civil rights and Title IX coordinator, by email to clarify why the office had issued a deferred suspension after the outcome was removed, but he didn’t respond.

In an earlier email exchange, however, Jones acknowledged the removal of deferred suspension as an outcome in the LSU Code of Student Conduct, writing that the office wouldn’t use deferred suspensions. And yet, according to the office’s Fall 2023 data report, it did.

Jones indicated by email that there was a second finding of responsibility where the perpetrator wasn’t removed from campus, but he didn’t specify whether this was a deferred suspension.

Understanding the Title IX office

The stated goal of LSU’s Title IX office is to strive for a campus “free from discrimination based on sex including all forms of sexual assault, sexual harassment, dating and domestic violence, stalking, power-based violence, and retaliation.”

To those ends, the office has three main functions: to offer preventative education on sexual discrimination and violence, to receive reports of sexual discrimination and violence and seek resolutions for those reports, according to its website.

The university receives about 280 reports involving sexual discrimination, harassment, assault and power-based violence each year, according to the Title IX office’s twice yearly data reports.

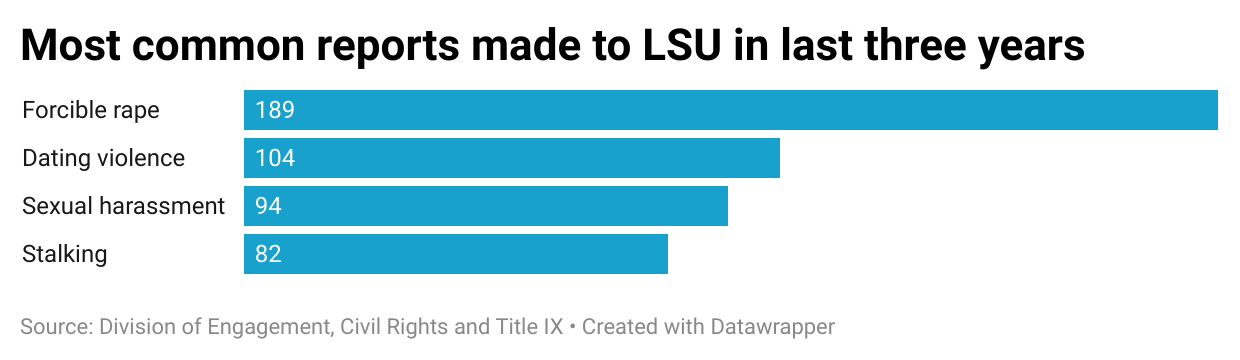

Many of those reports are for serious violations.

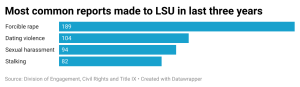

From June 2021 to September 2023, 28% of reports were for “forcible rape.” Another 16% of reports were for dating violence, and 13% were for stalking.

A large share of those who file initial complaints don’t respond when the Title IX office follows up with them. In the most recent Title IX data report, over half of reporters were unresponsive, but the report is unclear on how exactly the office reaches out to students who make reports.

The second largest share of reporters in the most recent report, 21%, asked the office for supportive measures rather than a formal resolution. Most of that support was academic in nature, according to the most recent review, providing accommodations such as excused absences and extended deadlines.

Other reports ended for clerical reasons: if it turns out LSU doesn’t have jurisdiction over the report — such as in instances where the violation occurred off campus — or if the survivor reported anonymously, for instance.

For survivors who pursue a resolution, Title IX offers two main pathways: formal and informal.

Formal resolutions, according to LSU’s Title IX website, are reviewed by the Title IX coordinator and assigned an investigator. They pass through a two-step process involving, first, an investigation where both parties gather evidence and, second, an adjudication.

Both sides present their evidence to a three-member hearing panel, chosen from faculty and staff or administrative law judges. Both parties are questioned by their own representative — often a lawyer — and the opposing side’s representative.

“The Title IX regulations dictate that we have to have a live hearing where a complainant has to face the respondent,” said Asha Murphy, deputy Title IX coordinator for response and resolution.

This daunting prospect, coupled with only a chance of the desired outcome in a formal investigation, often steers students away from pursuing that option.

Following a hearing, the panel members decide whether the alleged perpetrator is “responsible” or “not responsible.” They use a preponderance of evidence standard, meaning they must decide whether it is more likely than not that the person committed the violations.

These panels also determine the consequences if they find a violation of the Title IX policy has occurred. Both the decision of responsibility and the sanctions can be appealed by either side.

Of the 11 formal complaints that went to a hearing through LSU’s Title IX office since July 2021, eight respondents were found responsible and three were found not responsible, according to data provided to the Reveille by Jones. Of the eight found responsible, six were removed from campus, and two were not.

An informal resolution, on the other hand, is a voluntary process agreed on by both parties that takes on a much more organic form, changing from case to case.

According to the Title IX office, some students choose the informal process because it gives them more control, can be finished quicker and doesn’t require survivors to rehash the details of their experience to the same extent that a formal resolution would.

According to Jones, 11 formal complaints have been resolved through an informal resolution process since June 2021.

“It’s a little bit more restorative based, but it’s also something where the complainant kind of has a little bit of control,” said Kristen Mathews, an LSU Title IX case manager.

READ MORE: LSU settles Title IX lawsuit for $1.9 million

Gaps in knowledge and trust remain since public revelations

In the past, LSU has struggled to uphold its responsibilities under Title IX, a federal rule banning sex-based discrimination in educational programs and activities. A 2020 USA Today report detailing LSU’s mishandling of Title IX cases caught national attention and spurred campus protests — and was followed by a lawsuit by 10 former students that settled in March for $1.9 million.

Another report by The Advocate in 2021 revealed a former LSU graduate student had sexual assault allegations from seven women. Six of them filed a federal lawsuit against LSU saying that the university failed to investigate their reports.

The USA Today report — and subsequent calls to action on campus and from state leaders — resulted in LSU commissioning the law firm Husch Blackwell to study its Title IX handlings, which ended in a March 2021 report.

“The University did not handle various items identified in the USA Today article in a manner consistent with obligations under Title IX, widely recognized best practices and University policy,” the report read.

Among a list of 18 recommendations, the report also concluded that the LSU Title IX office was neither appropriately staffed nor provided with adequate resources to carry out its duties.

Thomas C. Galligan Jr., then LSU’s interim president, said the university had “betrayed the very people we are sworn to protect.”

In December 2021, the university contracted another law firm, Baker Tilly, to review what progress LSU had made toward addressing the recommendations outlined in the Husch Blackwell report. It found the Title IX office had addressed 10, while eight still remained either in progress or unchanged. The Baker Tilly report concluded, namely, that the Title IX office needed to continue to assess its preventative training and education programs.

The report also found that, in two out of five LSU Title IX cases they reviewed, important documentation was missing from case files.

Through interviews, the Reveille found some LSU students aren’t familiar with the Title IX office or wouldn’t feel comfortable going to the office to report an incident.

Out of 10 students interviewed at random by the Reveille, four had no knowledge of the Title IX office or how it functioned. Other students, who had heard of Title IX, said they thought the office could improve its visibility and outreach on campus.

Biology sophomore Melanie Suarez said she thought the office should make more of an effort to inform the LSU community about who they are and what they do, especially on social media.

Several other students interviewed by the Reveille also said they thought the office should have a stronger presence on campus.

“I don’t hear too much about it, and I’m not really sure … if it’d be handled in a good manner, that I’d be comfortable with my information being safe,” Suarez said.

Out of the 10 students the Reveille interviewed, four said they wouldn’t feel comfortable going to the office for help.

Nutrition pre-med sophomore Corinne Bosch was one of the students who knew what Title IX was and had a general understanding of the kind of support the office offered. She said she wouldn’t feel safe reporting to the office.

“I feel like it would get back that I said something,” Bosch said.

Biology sophomore Maddie Gilley said she thought sexual discrimination, harassment and assault was an especially big problem in the South. Bad experiences with her high school counselors in Louisiana had made her weary of seeking help at school offices.

Architecture sophomore Kamu Pancholi was one of the students who was familiar with Title IX and the mission of LSU’s office. She said she’d feel comfortable contacting the office to report an incident, but she thought the office could improve their accessibility.

“One gripe that I do have with the Title IX office,” Pancholi said, “is they make it really hard to figure out the resources they have or what will happen if you go to them — like your options.”

Pancholi said she thought the office’s website was difficult to parse and overly focused on legal jargon that doesn’t really assist students who are seeking help.

“I think if they make it more straightforward, or try to get the word out more for what they can offer students and what certain actions would mean for them, it would be much more helpful to and accessible for students,” Pancholi said.

The LSU website for Title IX has information on resolution options, supportive measures for alleged perpetrators and victims, and opportunities for training and workshops. The office also has an Instagram page that posts regularly.

The Reveille contacted LSU’s Title IX office several times for this article, but the office was mostly unresponsive. A Reveille reporter contacted the Title IX office over the phone five times and went to the office in person twice. They were referred to contact Jones, the Title IX coordinator.

In total, Reveille staff emailed Jones more than 10 times, attempting to clarify data or meet Jones for an interview. Jones took more than a month to reply to questions about the data.

Changes to the office in recent years

A 2021 act passed by the Louisiana Legislature made it law that higher education institutions in Louisiana have to create twice-yearly reviews on power-based violence, including data that describes how many reports the school received and how those reports were closed. Because of that law, students now have access to the data used as the basis of this article.

Almost all LSU employees are mandatory reporters, meaning that they are required by law to file a report with the Title IX office if a student tells them about a potential Title IX violation.

This role was clarified after the 2020 Title IX revelations, in which some employees who were required to make reports failed to do so.

Students confiding in professors, residential assistants or any designated mandatory reporter may not know they have an obligation to contact Title IX. For students who don’t want a report made, that can be problematic.

“It should be a confidential matter,” said Mendy Escudier, a sexual assault investigator at the East Baton Rouge coroner’s office, “but the introduction of the duty to report for the safety of the campus has blurred the lines.”

Confidential reporters, on the other hand, are trained to help students find resources and care, and they’re not required by law to file a report. Over the past years, the university has increased the number of confidential advisors on campus from 24 to 30.

LSU’s Lighthouse program provides the LSU community with a staff of confidential advisers and can help survivors with finding medical care, evidence collection, navigating Title IX or reporting to the police.

The university is also involved in a two-year program called the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators to address and prevent sexual violence on campus with student affairs organizations. That partnership saw the creation of a new support group for survivors of interpersonal violence launched at LSU in late February, funded by the Title IX office and NASPA and in partnership with LSU Student Government and the LSU Psychological Services Center.

READ MORE: Is LSU’s Title IX Office affected by new power-based violence legislation? Not really, coordinator says

Sexual assault on college campuses

While the number of crimes on college campuses per 10,000 students has gradually decreased over the last decade, the number of sexual assaults per 10,000 students increased, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

The beginning of the year is crucial for freshmen and transfer students who are navigating a different school, trying to make new friends. In a culture where entertainment and fun are closely tied to drinking, many sensitive concepts surrounding LSU nightlife often go overlooked.

A phenomenon known as the “red zone” describes the time of year that rates of sexual assault surge on campus: during the first few weeks of the fall semester. About half of all cases nationwide occur during this period, according to a peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of American College Health.

And while common conception of perpetrators often centers on roofies and back-alley attacks, these stereotypes of sexual assault are less common in the real world.

“Everyone wants to talk about roofie drugs, but alcohol is the number one date rape drug,” Escudier said.

Another common misconception is that perpetrators of sexual assault are most typically strangers. The reality is that they often lurk within social circles.

“We know that sexual assaults occur between people who know one another in some way,” Murphy said.

For survivors

The East Baton Rouge coroner’s office provides supportive measures for survivors of sexual assault.

“You can choose to have a kit done,” Escudier said, “but you don’t have to report to law enforcement.”

The LSU Lighthouse Program and Baton Rouge nonprofit Sexual Trauma Awareness & Response also provide confidential services for survivors. STAR has a 24/7 hotline, which can be found on its website. LSU student organizations, like Tigers Against Sexual Assault, work to raise awareness about sexual violence on campus, too.

If you have had an experience with sexual violence or Title IX that you would like to discuss with the Reveille, you can reach us through our anonymous tipline, on our social media or at [email protected].

Courtney Bell contributed reporting to this article.