About eight million metric tons of plastic waste enter the oceans from land each year. While plastic production is increasing every year, so is the amount found in fish bellies.

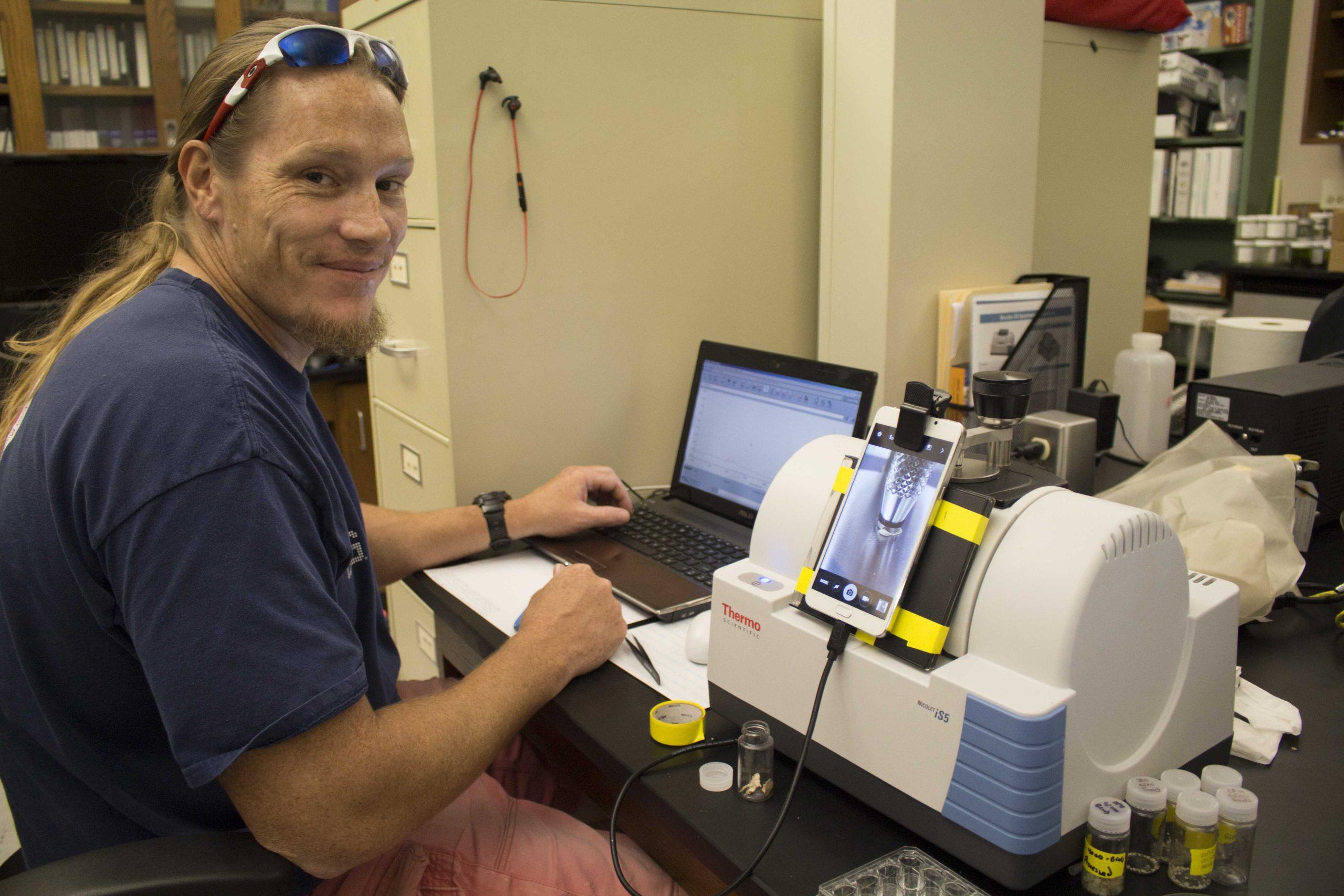

LSU Department of Oceanography & Coastal Sciences Professor Mark Benfield and his team are the first to survey the amount and type of plastic found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Whether it is microbeads from face wash, synthetic fabric lint from laundry, rubber tires, toothpaste or even cosmetics, factories are producing this plastic that is making its way into water systems, Benfield said.

“What we’re trying to do is understand how much plastic is being transported by the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico, that’s the first question, and to understand what’s the relative contribution of Baton Rouge and New Orleans,” Benfield said. “So by measuring the amount of plastic in the river above and below each of those cities, we can look at the differences and try to get a handle on how much each city is producing.”

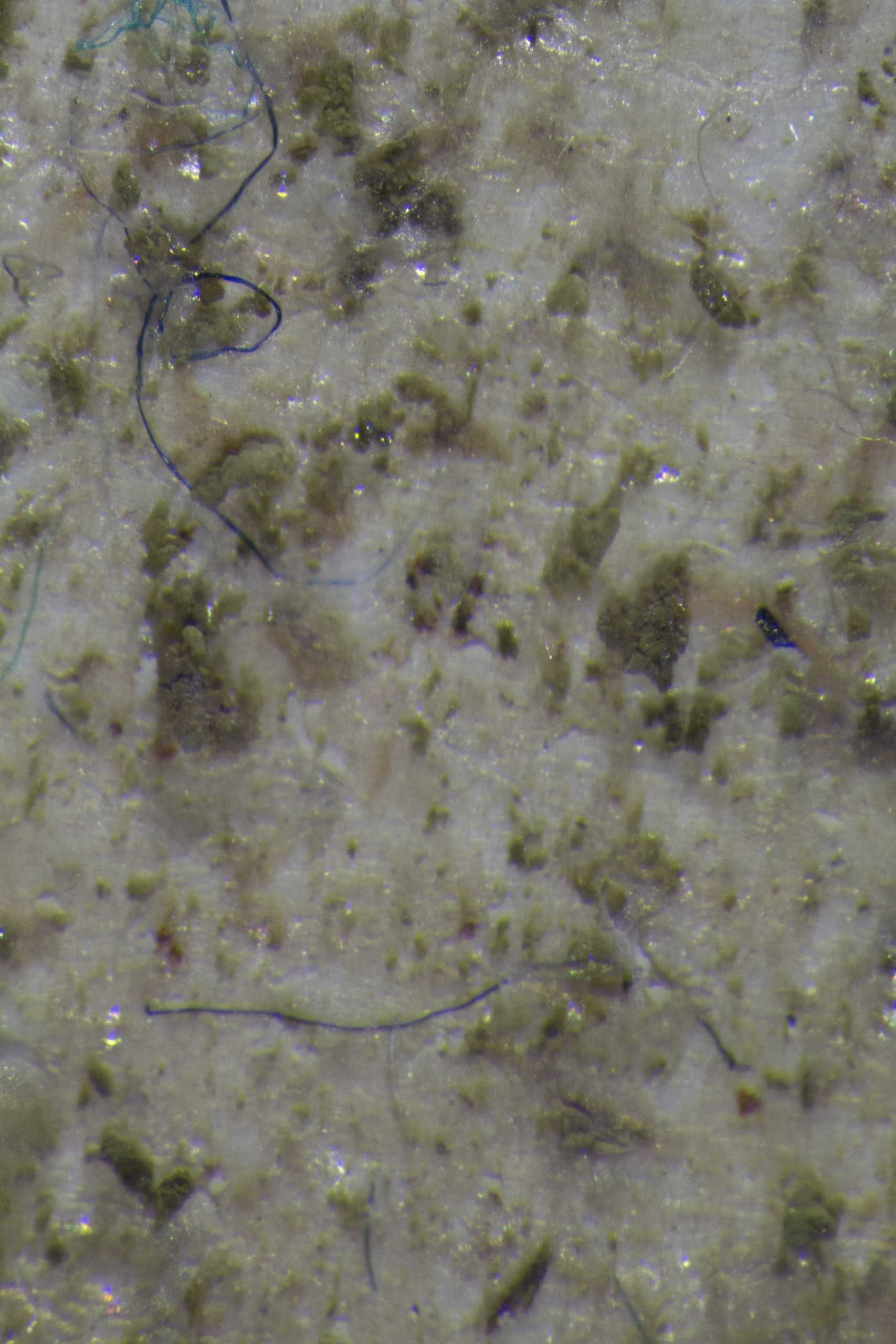

Benfield and his colleagues, postdoctoral researchers Matthew Kupchik and Rosana DiMauro, first started researching microplastics in the Gulf of Mexico in 2015. They collected water samples at four locations in the northern Gulf of Mexico from the surface of the Gulf down to about 15 meters deep. Every sample they analyzed contained some kind of microplastic. The study found that the concentration of microplastics in the Gulf was among the highest in the world, according to a news release.

“The big challenge is that those things are about the same size as the natural food that larval fish would eat,” Benfield said. “They’re about the same size as tiny single-celled plants that zooplankton would eat, so now there’s a way for this stuff to get into the food web.”

A sample from the stomach contents of an Atlantic bumper, who feed on zooplankton, revealed plastic. Plastic, because of its surface chemistry, is like a sponge for organic pollutants Benfield said.

“If they eat a lot of plastic, they can accumulate persistent organic pollutants, and as bigger animals eat them, it gets passed up the food web and magnified,” Benfield said. “Ultimately, if these things get into our food supply, then we’re ingesting the contaminants associated with all that plastic.”

Benfield said he plans to continue this research further at the University and to study the role of river diversions.

“What I hope to do is to set up LSU as a center for plastics research to study both the impact on human societies and on natural environments and bring faculty and students from across the campus,” Benfield said. “We’ve just submitted a proposal to look at the role of river diversions which are used to create land in transporting micro plastics into our estuaries and we also want to look at plastic contaminates that might be ingested by people here in Baton Rouge.”