A team of University faculty and students are researching landslide deposits in Gulf of Mexico seabeds.

Since its discovery in 2001, the S.S. Virginia, a sunken oil tanker in the Gulf of Mexico, has shifted 1600 feet due to underwater landslides occurring in the Gulf.

Researchers at the University worked with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the US Geological Survey to study the seabeds where submarine landslides occur in the Gulf. The Bureau funded Samuel Bentley, a professor in geology and geophysics at the University, along with Kevin Xu, an assistant professor of oceanography at the University, and their research team to core the area where submarine landslide deposits occur.

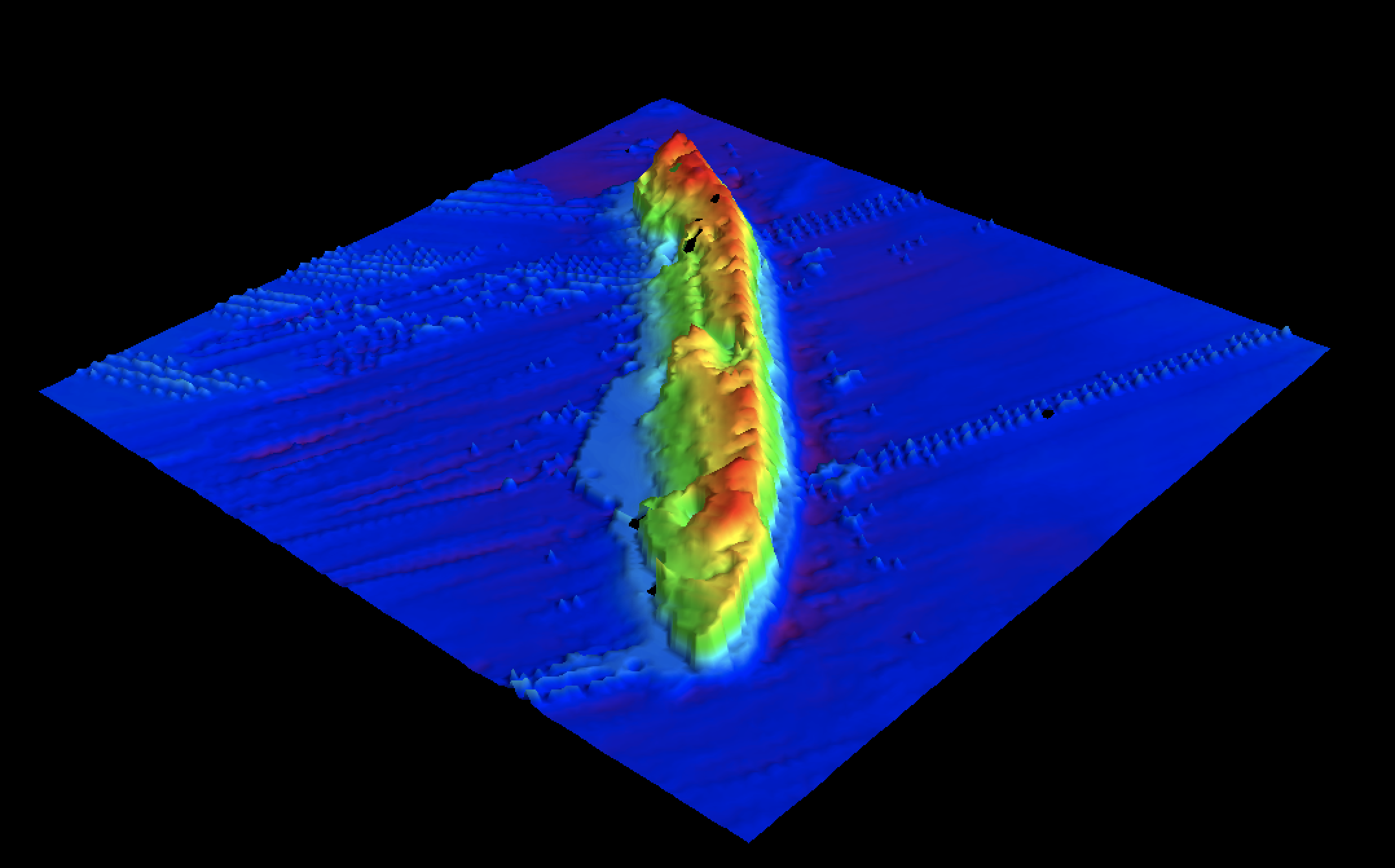

The USGS created high resolution, seabed maps of the area so the researchers could see which locations they needed to core, or dig into. To retrieve the mud and sediment, Bentley’s team took piston cores — 30-foot pipes — and dropped them into the seabed, allowing them to bring 10-meter long seabed samples to the surface.

“We study that to date the sediments, measure their strengths and to see if they might have zones of weakness prone to land sliding,” Bentley said.

These submarine landslides can be quite significant, Bentley said. Hurricanes with forceful waves can cause underwater landslides, damaging submarine infrastructure such as pipes, oil wells and oil platforms, and can cause oil spills.

“My research team just recently published a paper where we actually found evidence for even winter storm waves causing small submarine landslides to occur on a regular basis — that’s new,” Bentley said. “We know something about the annual time scale, something about the really big storms, but we don’t know anything about the in between.”

Another way the landslides occur is when sediment from the Mississippi River is dumped offshore into the Mississippi River Delta, so much to where it becomes “over-steepened,” he said.

“You’ve probably watched a dump truck emptying sand into a pile,” Samuel Bentley said. “It can only build a pile of sand that’s just so steep, and if it gets steeper than that, it collapses. The same thing happens with mud underwater. The river is piling the mud up, very steeply, and so these landslides [occur] to let the angle of repose, as we call it, decrease. It’s a natural part of how the sediment deposits form and equilibrate to the submarine landscape.”

Shaped like an apron, the River Delta Front wraps around the Delta, and only a small portion of this area is currently mapped. The area was mapped in the 1970s, but since then the river has changed and technology has improved for researchers to better study and understand the front.

The research his team is doing will prove that this environment can be successfully sampled and mapped, Bentley said, so they can eventually map the entire river delta front.