When Alexander “A.P.” Tureaud Jr. became the first black undergraduate student admitted to LSU in 1953, he knew his situation would get ugly very soon.

“It was probably one of the worst experiences I had ever been through,” Tureaud said. “I was totally isolated and nobody spoke to me.”

Tureaud said he knew people would treat him badly, but the severity of the abuse surprised him.

“I think the word was out — ‘We gotta get this man out of school,’” Tureaud said. “One of the professors even said to the class, in my presence, that she didn’t think she could touch my papers.”

The campus attitude toward Tureaud reflected the rest of the nation at the time. Segregation was still widespread across the country, Tureaud said, and people fought back against blacks who tried to make a better life for themselves.

As a child, Tureaud said he can remember lynchings and bombings at African-American homes in New Orleans, where he grew up. He said police would often ignore or not take seriously these incidents.

He said his family was lucky enough to never have their house bombed or otherwise attacked, but they did receive threats.

While some consider the southern U.S. to have more racist attitudes overall, Tureaud said he experienced the same prejudice around the country.

Tureaud Hall is named after his father, Alexander Tureaud Sr. who was a champion of black civil rights in Louisiana and worked on over 100 civil rights cases.

Tureaud Sr. was a lawyer in New Orleans, and his son said for many years he was the only black lawyer in the state. Tureaud Jr. also said his father worked for the NAACP for 45 years and never billed them for his services.

In 1941, Tureaud Sr. successfully sued the state in Mckelpin v. the Board of Education for equal pay for black teachers. In 1952, his case Bush v. Board of Education led to the desegregation of public schools in New Orleans.

Tureaud Sr. had to sue the state for his son to be able to go to LSU.

While Tureaud Jr. only spent 55 days at LSU due to his father’s suit ending in a mistrial, he said his time at the University had the media in an uproar.

Tureaud Jr. said when his father came to pick him up after the mistrial, he felt relieved because the decision had been taken out of his hands. He did not want to give up on his own because he felt like he would be failing other African-Americans.

“I realized after about three weeks that this wasn’t gonna work,” Tureaud Jr. said. “I didn’t want to be a victim and I didn’t want to be a failure.”

The only people that spoke to Tureaud Jr. freely were black maintenance and cafeteria workers. They understood the weight on his shoulders, and Tureaud Jr. said they were always friendly with him. He said the cafeteria employees often piled his plate with more food than he could eat.

Tureaud Jr. also knew some of the black graduate students, who faced similar treatment on campus. One married couple he knew lived in a small house at one end of campus. The woman was noticeably pregnant, and Tureaud Jr. said she told him while she walked across campus, students would approach her and ask if she was “having a gorilla.”

One of the few times Tureaud Jr. can recall a white student speaking to him was an instance of mistaken identity.

Tureaud Jr. always got to his racquetball class early to make sure he had somewhere to play. One day a white student came to play with Tureaud Jr., who is light-skinned, and said he did not necessarily appear black to everyone.

“I’m glad you’re here,” the student told Tureaud Jr., not realizing who he was. “I don’t wanna play with that n—– A.P. Tureaud.”

The instructor always called roll at the end of class, and Tureaud Jr. said the student’s facial expressions were quite amusing whenever Tureaud Jr. answered present to his name in front of the whole class.

Ignoring his existence was not the only way people tried to upset Tureaud Jr. He said many times he came home to his dorm to find trash thrown by or on his door. On one occasion, around Halloween, Tureaud Jr. said someone left roadkill on his door.

While Tureaud Jr. knew other students would be harsh, he said he thought the professors would at least act professional, if discourteous, toward him, but they did not acknowledge him either. When he would ask a question about classwork, they would give no response.

Tureaud Jr. said once he had moved on with his life and began his career and family he never intended to return to LSU. But in 1989, when the University first began the A.P. Tureaud Sr. Black Alumni Chapter, he knew he had to come back and help.

Today, Tureaud Jr. is retired, but still takes on projects with people to help advance the African-American community. He also enjoys painting, which he said he taught himself. Tureaud Jr. said he has always enjoyed traveling, and every year he spends time in Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts and his main residence in Connecticut.

Tureaud Jr. still comes back to the University for various events. In 2011, the University granted him an honorary doctorate, and last spring he was the keynote speaker for the College of Art and Design’s graduation ceremony.

“I don’t dwell on the victimization — I dwell on positive things about what we have to do to find a way to make yourself the person you want to be,” Tureaud Jr. said.

First black undergraduate student at the University recounts vile treatment he received on campus

February 26, 2019

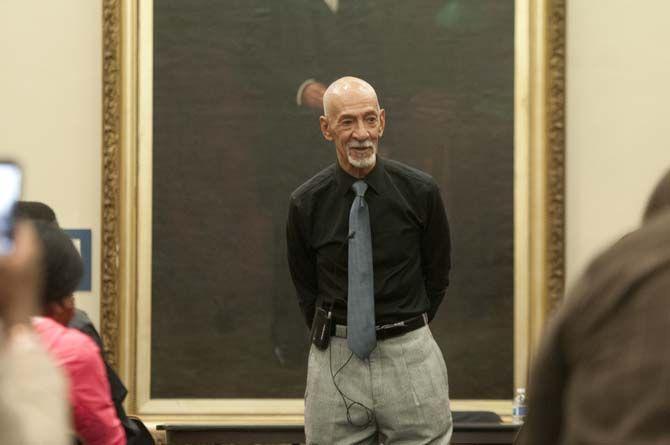

LSU civil rights figure A.P. Tureaud speaks to students on Tuesday, April 14, 2015, at the Hill Memorial Library about his experience as the first black student to attend LSU.