Homecoming at LSU is steeped in tradition, and the selection of the homecoming court is no exception.

For students named homecoming king and queen, being crowned to thunderous applause by the tens of thousands of LSU students and fans in Tiger Stadium is a once-in-a-lifetime moment.

However, there was a time when some University students have been historically barred from this honor, despite their achievements.

Renée Boutte, the first black homecoming queen at the University, was crowned in 1991. But according to former LSU Student Government President Ted Schirmer, the University could have crowned its first black queen in 1976.

Schirmer, who served as SG president in 1976, told The Reveille in September about the attempts to rig the 1976 election for homecoming queen in the hopes of addressing the racist attitudes of the time and make strides toward rectifying the situation.

Schirmer said the homecoming election of 1976 was set up to ensure that a black member of homecoming court, Cynthia Payton, would not be elected queen.

Schirmer said the men he appointed to run the election changed the voting process, requiring students to vote for three candidates instead of one. As a result, many people who wanted to vote for Payton were forced to also vote for the other white candidates.

A Reveille article from 1976 confirmed the three-vote ballot requirement. The voting initially started as a one-vote ballot, but the next day the Homecoming Committee changed it to the three-vote system, according to the story.

The Homecoming Committee co-chairman at the time, Mike Williams, said in the article he changed the voting procedure because “it gives more girls the opportunity to be elected, since they have a three-in-ten chance rather than one-in-ten.”

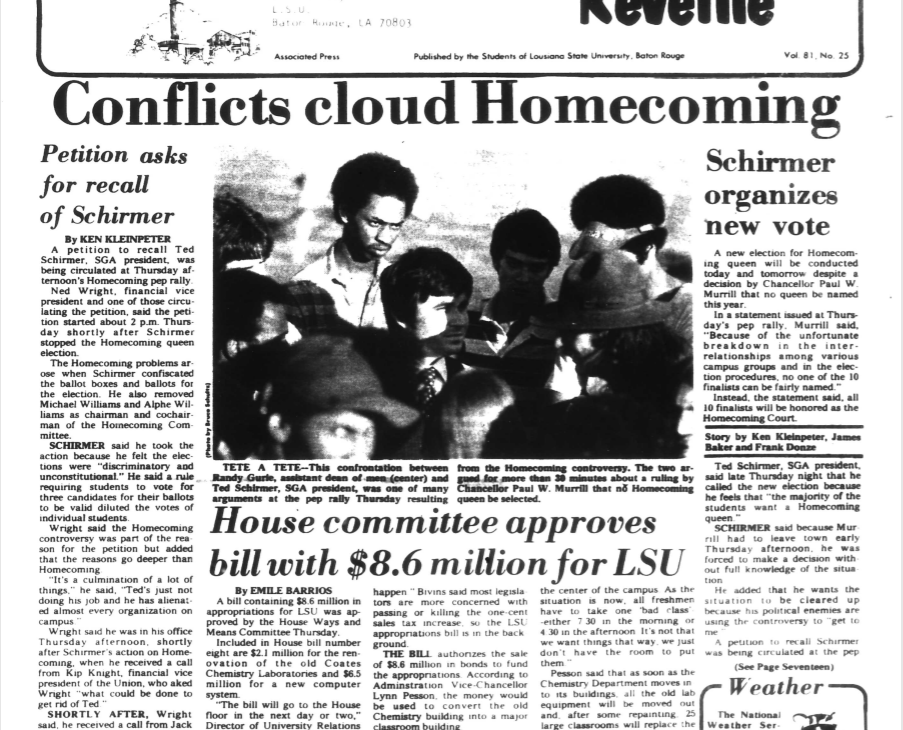

Schirmer, angry at what he perceived to be a racist and discriminatory voting process, fired the two co-chairmen he appointed to run the election. He subsequently halted the election and initiated a new one, despite then-University Chancellor Paul W. Murrill’s decision that no homecoming queen would be elected due to the controversy surrounding the election.

Schirmer said Murrill was speaking at an out-of-town event that night, so he called the sheriff’s office of the town and said he was LSU’s student body president. The sheriff’s office then connected Schirmer to Murrill.

“I told him, I said, ‘Paul, I don’t give a s–t what you said, we’re going ahead with homecoming,’” Schirmer said. “I said, ‘if you want to somehow stop us with going ahead with this event, good luck.’”

However, Schirmer’s election was formally disregarded several days later. A Reveille article from 1976 stated the homecoming queen finalists met with Murrill and agreed a queen should be crowned from the results of the initial election.

The confusion and controversy surrounding the homecoming election stirred opinions across campus. A scathing letter to the editor by Jo E. Myers in The Reveille castigated SG and the Homecoming Committee for the way the election played out.

“Is this a joke? Do you think that we are that unaware, naive, ignorant?” Myers wrote. “This is a supreme insult to blacks, the student body, and myself. How dare you insult me with your pettiness?”

Another letter to the editor was written by four members of the Homecoming Committee: Kathy Finley, Larry Hoskins, Mary Morales and Patty Rowland. The group said the three-vote system had been in place for at least two years prior in order to discourage black votes.

The committee members said much of the confusion came from their confusion over who the committee answered to. They criticized Schirmer for overstepping his bounds as SG president and said he attended only one committee meeting.

“Who does [Schirmer] think he is?” the group wrote. “SG president is not the highest office in the land as he seems to think. Does he have the right to tear down signs and remove ballot boxes if he wants?”

Schirmer also said Alphe Williams, one of the committee co-chairmen, was black, which is worth noting given the accusations of racism being the primary driver behind the three-vote ballot requirement.

Seemingly as a result of Schirmer’s interference with the election, a petition began to circulate for Schirmer’s recall as SG president. The recall failed, but after hearing from a friend the administration was printing flyers about the petition, he told a group of people at Free Speech Plaza exactly that.

The administration then used those statements to get the University Court to convict him of violating the Student Code of Conduct for “telling a lie with the intent to deceive.” He said a dean tried to expel him, but Murrill allowed him to remain a student and SG president after he agreed not to discuss the matter for one year or to run for re-election.

The Reveille ran a spread featuring student opinions on the potential removal of Schirmer from office. The opinions were mostly split: some said he interfered with matters outside of his control, others said they respected him for standing up to the administration. Some said no only because they found him entertaining.

“No, he’s the most interesting thing that’s gone on around here. I voted for him so I’d have something to read in The Reveille,” said student Doug Stafford.

Schirmer said LSU Greek Life was highly racist at the time, and few members, if any, would have voted for Payton along with their own members.

“When you look at this stuff, just like [former LSU President Troy] Middleton’s letter [against the racial integration of the University], you take a look at this [and] it’s black and white, literally,” Schirmer said. “This was a racist school.”

Schirmer said racism was a big problem on campus at the time. He said black students were spit on, had drinks thrown at them, were not let into bars and had trouble renting apartments.

A 1976 edition of The Reveille recounted an incident where a black woman named Cecilia Moses tried to attend the “all-white” Douglas Avenue Baptist Church, only to be asked to leave. The article also said the pastor of the church confirmed it had a policy of excluding blacks.

The selection process has changed over time, but homecoming court hopefuls currently have to successfully complete an application and interview process to secure their place in LSU homecoming history.

Homecoming court applications for this year were due on Sept. 8. After the Office of the Dean of Students verifies students’ eligibility, candidates’ first round applications are reviewed by at least three LSU faculty and staff judges. The Homecoming Student Committee’s Court Committee selects faculty and staff they feel would be good judges of candidates’ achievements and character.

Judges score candidates in four main categories: contributions to campus life, service, strength of application and potential to be a good ambassador for LSU. Students’ GPAs are also considered and are scored on a five-point scale

Following the week of first round applications, the 34 candidates who are selected to advance then participate in an interview conducted by a completely new set of judges. The students, alumni, faculty and staff who are selected to be judges score the applicants in the four categories used in the first round application review.

Candidates’ highest and lowest scores in each category are dropped in this round, which produces an average score for each candidate based on remaining scores. Once the scores are tallied and processed by the Homecoming Court Chair with Court Advisor, the 14 applicants selected for the homecoming court are announced.

Former SG president alleges racism in questionable 1976 homecoming election procedure

October 10, 2019