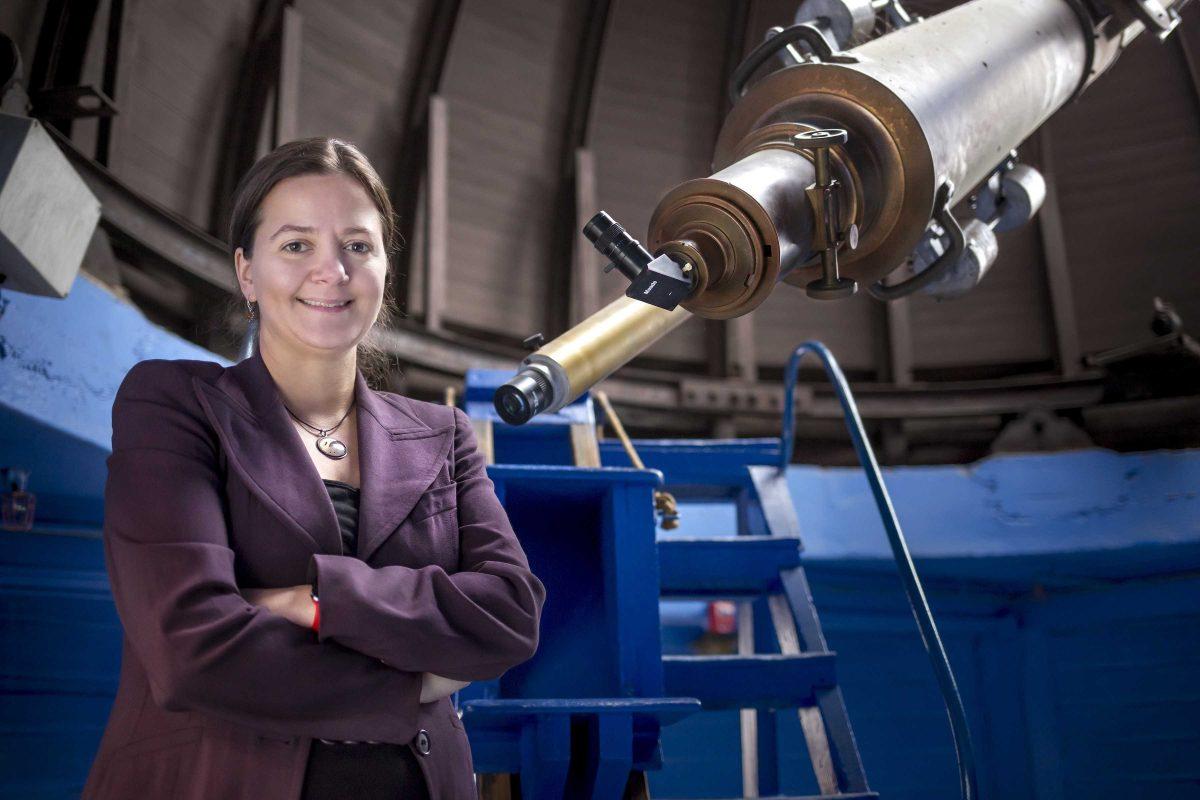

Tabetha Boyajian is an assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics here at LSU. She is also the namesake for Tabby’s Star, a star some 1000 lightyears away that has perplexed astronomers for years.

The star’s fame comes from its seemingly inexplicable and random cycles of brightening and dimming. Astronomers have debated about what might be obstructing its light, and possible ideas have ranged from planet collections to mobile alien megaships.

In 2017 Boyajian worked on a science team in a citizen-science program that involved the general public contributing observations based on data and images from NASA; Tabby’s Star eventually became a focal point. A colleague from Penn State University eventually referred to the celestial body as “Tabby’s Star,” and the title stuck.

According to Boyajian, suspicions of extra-terrestrial causes helped propel the story to stardom.

“Another colleague remarked that we simply couldn’t figure out what’s happening with the star and that it made for an interesting target in the search for extraterrestrial life,” Boyajian said. “That interpretation is how the star got really popular.”

These explanations arose because Tabby’s Star seemingly really does defy conventional explanations. But as posited by Boyajian in a paper in 2017, space dust is currently the predominant theory about Tabby’s Star. Dust seems consistent with the waning brightness, but the explanation is not without holes.

“If space dust is orbiting the star and absorbing its visible light, you expect it to reemit light in the infrared. That’s not what we see,” Boyajian said.

The absence of infrared emissions is still a source of some confusion, but the dust-theory has been reconciled with new data looking at what parts of the visible light spectrum are absorbed. Observations show that whatever is obstructing the light from Tabby’s Star has differential absorptions consistent with space dust. That is, visible light, such as red or blue light, is as a percentage absorbed at rates comparable to the known absorptions measured in space dust around other stars.

Another potential problem is the source of this space dust, according to Boyajian.

“We have to think about the mechanism that produces the dust,” Boyajian said. “When you have a star (like Tabby’s Star) burning hydrogen or helium in their cores, they lack dust. It’s all been blown away.”

In the latest news, other astronomers have hypothesized that the dust comes from an exomoon stripped from its planet by the star. In theory, the exomoon’s orbit was somehow perturbed and eventually burnt up by the star. The resulting debris orbits the star and eventually melts.

While the star cycles between bright and dim, its net apparent brightness has been observed for many years to be arcing towards increasingly faint. Boyajian said the star is now 20% fainter than it was 100 years ago. The exomoon theory sources the obstruction, but it is also apparently consistent with this gradual dimming.

Boyajian is still actively watching the star. She noted there was a detection two years ago of two dimming events that lasted for over eight months. She and her team hope to determine a pattern in the star’s fluctuations.