In the history of the LSU men’s basketball program, there are many names you can point to when talking about the greatest players, but no one comes close to the influence and legacy left by Collis Temple Jr.

When Temple stepped on LSU’s campus for the first time 50 years ago, he became the first Black scholarship athlete in LSU history.

Growing up in Kentwood, Louisiana, Temple lived a segregated, but relatively fortunate childhood. The son of a teacher and a principal, Temple and his family traveled often, which Temple attributes much of his worldliness at a young age to.

“By the time I was 15 years old, I had been to 48 states,” Temple said. “I would be in school learning about the states and capitals, and I could already visualize these things because I’d been there, which gave me an advantage in school.”

His traveling is also how he got his first college looks as a basketball player. One summer while attending a math and science camp at Kansas University, Temple caught the attention of then-Kansas basketball player Jo Jo White. After spending time rebounding for White while he worked out, White invited Temple to Kansas’ basketball camp that Temple attended multiple times while in high school. This put Temple on the radar of many programs in the midwest and introduced him to the recruiting process.

Despite all the traveling, Temple spent his childhood segregated in the heart of Jim Crow in South Louisiana. One experience that opened Temple’s eyes to this was attending a sermon when visiting California with his family.

“I remember being surrounded by people of all different races listening to a white man preach,” Temple said. “This was crazy to me because if you were Black and got caught listening to a white man preach in Kentwood, you would’ve been hung.”

This was the reality that Temple and many Black Americans had to live with at the time, no matter how much money or fortune they may have had. Socially, Temple’s childhood was segregated as well. Growing up, Temple never spent time with white people or made friends with white kids up until his late teenage years.

“My dad never let me hang around the white kids,” Temple said. “He didn’t want them degrading me or calling me a n*****.”

This changed dramatically for Temple, however, right before his senior year of high school. Leading up to the 1969-70 school year, the Fifth Circuit Federal Court ordered for school desegregation, requiring all high schoolers in Kentwood to attend Kentwood High School. A three-sport athlete in high school, Temple recalled the first team meeting when the order was announced, having to sit with the football players from the white high school.

“It was the most traumatic experience of my life to that point,” Temple said. “I had never been around white people before, and they made us sit in between the white kids who were already going to Kentwood High.”

The transition was difficult for Temple at his new school, both in school and in sports. Temple, who was once the quarterback and captain of the football team, was now a third-string tight end in an environment that neither he, nor his classmates from his old school were comfortable in.

Despite Temple’s difficult transition to his new high school, he continued to excel on the basketball court throughout his time at both schools. He would earn all-state honors his senior year as his new team went on to finish state runner-up. This would get the attention of LSU basketball Coach Press Maravich and Louisiana Gov. John McKiethen, who met with Temple’s family and discussed integrating the LSU basketball program. After a productive meeting, and much thought from Temple and his family, he became the first Black scholarship athlete to sign with LSU.

The transition was anything but easy for Temple, both on and off the court. While some of his teammates were supportive of him, others were not as happy about the idea of the team integrating.

“It was about half and half with my teammates,” Temple said. “It was part race and partly the pecking order — There were times where I could be wide open, but I knew they weren’t going to pass me the ball because of who I was.”

Then-Head Coach Press Maravich did not help Temple’s experience much either. Maravich was known by many as a racist, and it was not uncommon for him to make derogatory remarks around the team, Temple said. One year, Maravich was recruiting a star player named Louis Dunbar, who eventually spurned the Tigers to sign with Houston. The recruiting battle between LSU and Houston had been a long, frustrating process for all parties, and it seemed to boil over with Maravich.

“After it had come out that Dunbar was going to Houston, Coach Maravich called me into his office to talk to me,” Temple said. “I remember sitting down and him telling me that he’d never recruit another n***** again.”

In Temple’s third year, however, Dale Brown replaced Maravich as head coach and changed the culture of the team. Brown made the transition much smoother for Temple and provided an environment that was accepting and inclusive, unlike Maravich.

“I heard Maravich say n***** multiple times while he was the coach, and he would make derogatory remarks every now and then, but Dale Brown never did that,” Temple said.

Compared to Maravich’s own words and efforts to keep from recruiting Black players, Brown opened opportunities for Black athletes. Brown recruited players from all backgrounds, in turn bringing more Black players to the program, which did not sit well with a lot of fans early on. Brown recalled getting a letter shortly after getting the job from a fan calling him a “n***** lover.” Brown did not let the racist fans stop him, however, and he built a program that was inclusive and a means for change throughout the SEC.

Brown grew to be one of the most influential figures in the history of LSU for his work both on and off the basketball court. His career and legacy resulted in having the court at the Pete Maravich Assembly Center named after him, a decision that was led in part by Temple.

“Dale has done more for social justice in Louisiana than anyone I know,” Temple said. “I wanted to have the court renamed not necessarily for what he did on the court, but what he did as a humanitarian and for social justice.”

Despite the challenges that came with his time at LSU, Temple was able to enjoy success both on and off the court at LSU. In his senior season Temple averaged 15 points per game and 10.5 rebounds per game on his way to earning All-SEC honors. Off the court, Temple had an equally good year in the classroom, qualifying him for All-SEC Academic honors. Temple would finish his career with 679 career points and 472 rebounds, making him the eighth-leading rebounder in LSU history.

After finishing his basketball career at LSU, Temple had a brief professional hoops career before returning to LSU to get his master’s degree in Business Administration. He’s been involved with the school ever since.

Temple’s involvement with the university continues today in a big way as a member of the LSU Board of Supervisors. It was through this that Temple was able to push for the basketball court being renamed after Coach Dale Brown. Temple also had a role in the selecting of William Tate IV as LSU president back in May, making him the first Black president in the history of the SEC.

“It was the ultimate improvement,” Temple said when talking about what the selection of Tate meant to him.

His legacy on the basketball court lived on at LSU through two of his sons, Collis III and Garrett Temple. Garett, the younger of the two, helped lead the program to the Final Four in 2006 and is still an active NBA player, recently signing with the New Orleans Pelicans.

“I never really stopped being involved,” Temple said, talking about his relationship with LSU. “I still live less than a mile from campus to this day.”

“I just want to be remembered as a change agent.”

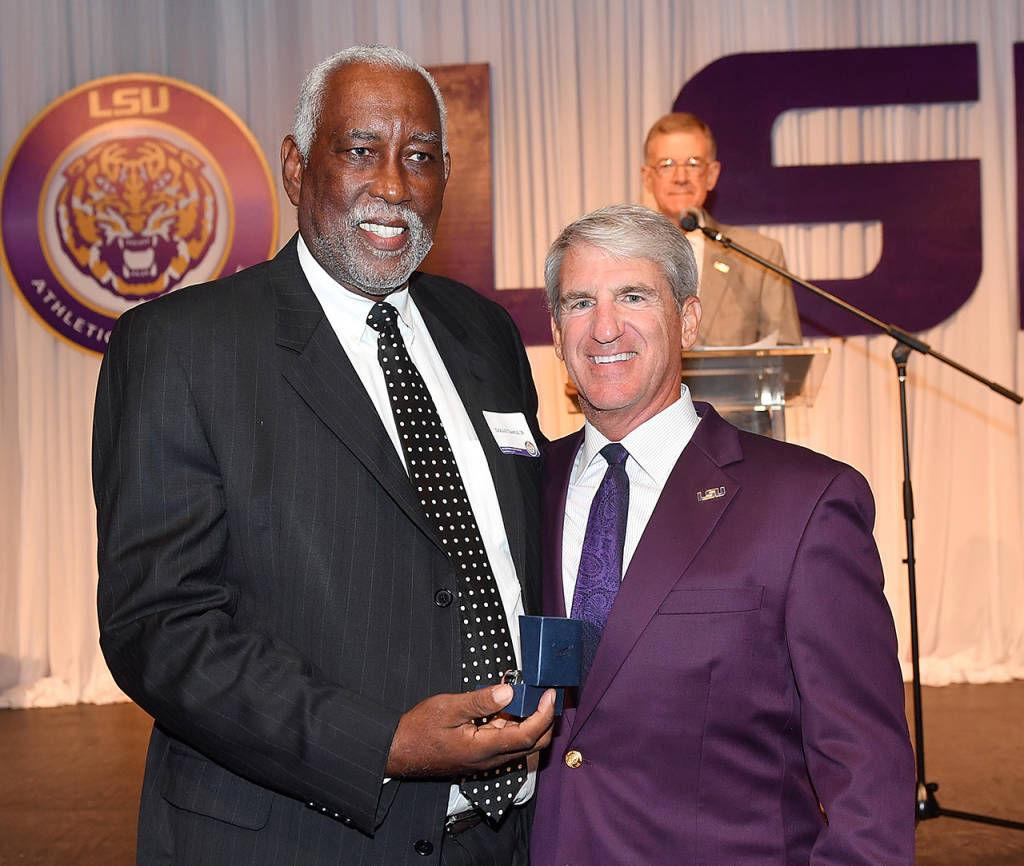

Collis Temple Jr. poses with LSU Athletic Director Joe Alleva at the LSU Athletics Hall of Fame induction ceremony on May 12, 2017.