During the summer box office run of Marvel Studios’ “Black Widow,” AMC 15 at the Mall of Louisiana gave out free comic book prequels to the film. After the showings, there was still a large stack of undisturbed copies, and many of the copies that were given out found their way to the nearest garbage cans.

Despite comic book adaptations enjoying more popularity than ever—with over a dozen new television adaptations premiering on various platforms and at least seven big screen adaptations opening—comic books themselves are not attracting the resounding readership of a blockbuster film’s audience.

For comic creators like Lafayette-native Rob Guillory, seeing comic-derivatives succeeding on such a global stage is bittersweet. On one hand, the characters he grew up reading are getting more attention than ever. On the other, the comic creators don’t serve to benefit when Hollywood adapts their work.

“Before the Marvel movies and all that blew up, the idea that comic people had was, ‘if we could just get our material in front of a larger audience, you know we can just make a Spider-Man movie, [then] that will sell more Spider-Man comics.’ It just hasn’t been true,” Guillory said.

Guillory, who has written and drawn comics for both Marvel and DC, is best known for his creator-owned work at Image Comics, including the recently-concluded “Chew” with writer John Layman and his solo creation, “Farmhand.”

In the nearly two decades since he left the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Guillory has been shocked at the large volume of people that are divorced from comics when “Avengers: Endgame” can gross nearly $3 billion.

“I knew something was wrong about six years ago when I was at a comic con in Shreveport. This couple comes up to me both wearing Avengers t-shirts, and I asked them, ‘what kind of comics do you guys like reading?’ They said ‘oh, we don’t read comics.’ You’re wearing Avengers t-shirts and you’re at a comic con but you don’t read comics,” Guillory said. “This is really bizarre.”

Those who study comics critically also acknowledge the disappointing reality of comic book sales and popularity in a world of successful adaptations.

“Evidence of recent years suggests that people are very happy to go see Captain America in a movie and don’t really have any interest in buying a Captain America comic if they weren’t already reading Captain America,” English professor Brannon Costello said.

With a focus on comics studies in the LSU English Department, Costello curated the Hill Memorial Library’s Bowlus Comic Book Collection, which includes over 7,000 comics from the ‘Silver Age’—the late 1950s and 1960s. Costello wrote a book titled “Neon Visions,” chronicling the career and stylings of cartoonist Howard Chaykin that was published through LSU Press in 2017.

He also teaches multiple courses on the study of comic books as literature, including a 4000-level capstone class for undergraduate English students and a graduate-level class about comic books in the south.

“It can be both useful but also limiting to think about comics as a form of literature. The comics that have gotten the most attention from scholars in comic studies are comics that look like more traditional literature,” Costello said.

Through his courses, Costello said he wants to impart that comic books are more than just superheroes, showing the contributions of nontraditional comics from underground and zine movements.

One of the most significant examples cited by Costello is “Love and Rockets” by Jaime Hernandez. The series, which started in 1980, has continued a single narrative thread about a group of Latino punk rock kids from Southern California.

“He has followed the same cast of characters essentially since he was a teenager up to now, and they sort of age in real-time. So it’s a really involving, really formally sophisticated exploration of these characters,” Costello said.

While Costello does still acknowledge the merit of costumed heroes within his courses, academics studying comic books feel the prevalence of superheroes in the medium hold comic studies under more scrutiny than other branches of literary studies.

As a graduate teaching professor during Spring 2020, English Ph.D. candidate Natalie Shepard taught a course titled “Introduction to Comic Books” that emphasized the breadth of stories that comics were able to tell. She also wanted to dispel misnomers about comics that she experienced as an academic.

“The superhero genre is a necessary part of comic studies and a necessary part of the history of comics, but that public perception that superheroes and comic books are synonymous and exactly the same thing is something I wanted to fight,” Shepard said.

Comic books can be about superheroes, but super-heroics are just one genre in the sea of sequential art.

Superheroes like the Fantastic Four and Batman are discussed in the university’s comic studies course, but are in the minority of the comics discussed.

Some of the literary comics that Shepard and Costello teach in their classes include “March” and “Maus,” the memoirs of late-civil rights activist and U.S. Congressman John Lewis and the son of Holocaust survivors Art Spiegelman, respectively.

“Comics are just another way to tell stories that are no different from film or prose,” Shepard said. She feels some comics have more complexity than some traditional texts taught in schools.

In recent years, Shepard has noticed a shift in how educators view comic books. In the past, she said, educators discredited comics as not real literature.

“Educators are realizing that comics aren’t some lesser form of reading, and that it can improve literacy in kids,” Shepard said. “I think we’re seeing a lot less of that ideology and more of people just realizing that comics can not only help kids be a gateway toward real books, but be valuable in and of themselves as a form of literature.”

Both Shepard and Costello feel that comics can be valuable in developing tools and skills needed to succeed in the 21st century, where visual communication is increasing at a rapid pace.

“One of the things that reading comics critically teaches you to do is to read images,” Costello said. “Not just to receive them, but to think critically about the ways that they’re made, the meanings that they generate or that can be imposed upon them, the ways in which multiple images can be put together in such a way to provoke a certain kind of emotion or communicate a certain idea.”

For both academics and comic professionals, comics–especially publications outside of Marvel and DC–provide for more freedom than any other medium.

“I think it is the most pure storytelling medium,” Guillory said. “You have the best of pure literary fiction sans pictures. You have the best of filmmaking; there’s a reason Hollywood is using comics as source material, because it is essentially a storyboard.”

“Sometimes there are stories you just can’t tell anywhere besides a comic book,” Costello said. “This uniqueness is what’s lost in adaptation to different mediums. When there is a really interesting synergy between a writer and an artist, they’re doing things aesthetically that simply can’t be translated,” Costello said.

Comic professionals and academics both agree that comics are still held back by outdated stigmas and misconceptions about the medium.

“I think there’s this misconception about comics, that they’re really difficult to get into, and you have to get in at No. 1 and read boxes and boxes and boxes of comics in order to understand what’s going on and that’s not necessarily the case,” Shepard said. “Especially now with things like digital platforms, I think it’s easier than most people think to pick up a comic and read.”

Shepard said that she feels it is important to promote comics like the recently adapted “Y: The Last Man” that are relatively short (at less than 10 volumes) that can be finished in a few weekends will help “eliminating the intimidation factor” of comics.

Comics aren’t a monolith, Guillory said. Comics can be deconstructive superhero narratives like Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” or memoirs like Emil Ferris’ “My Favorite Thing is Monsters,” the latter of which received praise from the New York Times.

“I think it’s been stigmatized as childlike for a really long time,” Guillory said.

Academics like Shepard and Costello and cartoonists like Guillory feel it’s time to fight that stigma.

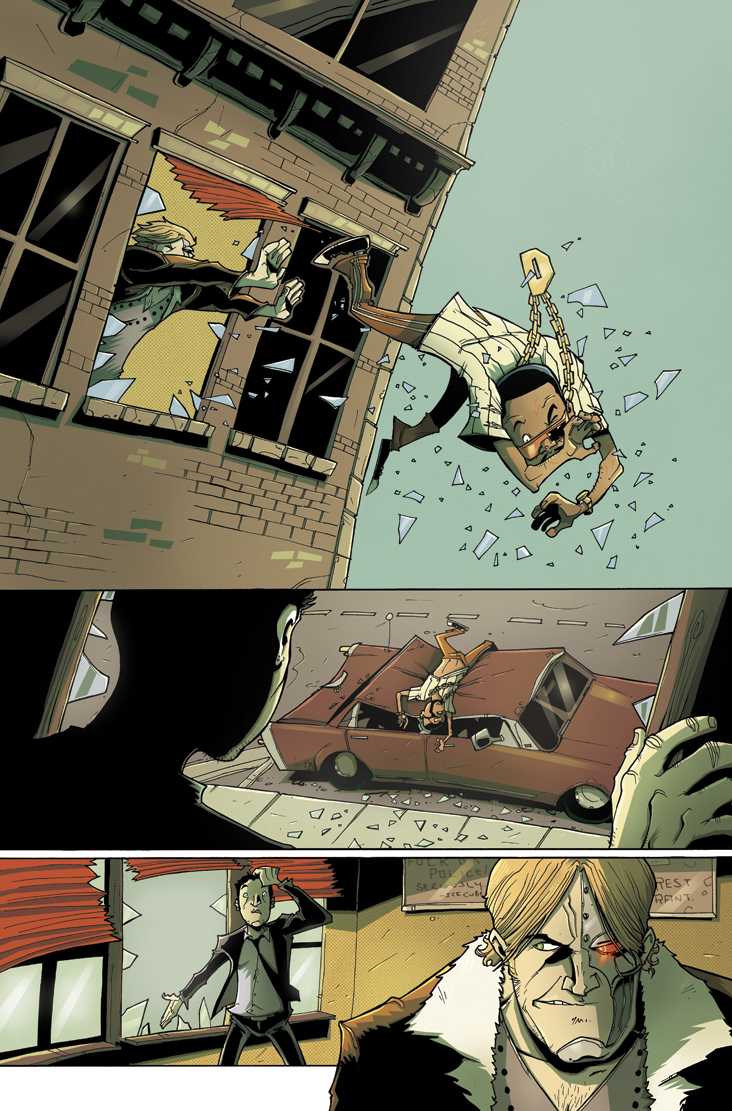

Artwork from "Chew" no. 6 by Rob Guillory published by Image Comics in 2009.