Louisiana’s very own three-toed amphiuma swims in our lakes and ponds, mingling beneath the ducks. Although out of sight, these creatures spend their time eating their favorite food—crawfish. Amphiuma are one of the largest species of salamanders, reaching up to 43 inches.

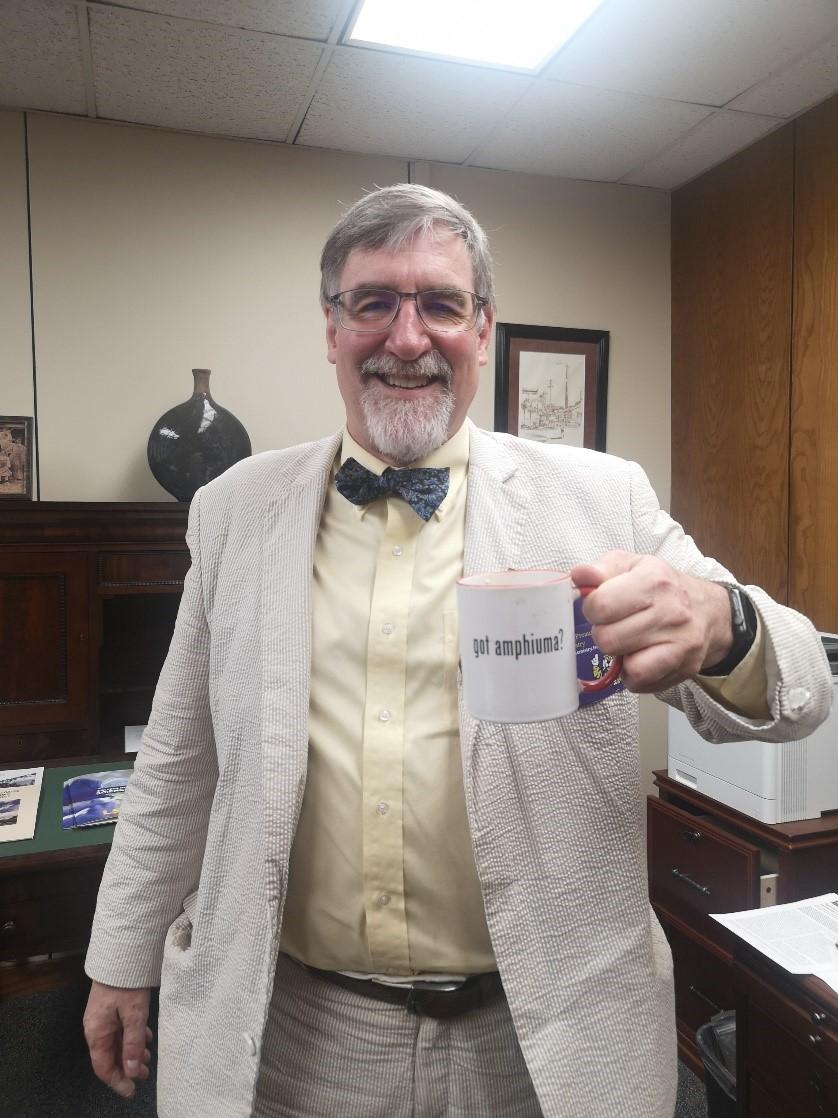

“I’ve seen them along Nicholson Drive because a lot of amphiuma live along there. It’s very easy to see them because the water is shallow, and you can see them walking up to prey to catch crawfish,” said Dr. John Pojman, award-winning chemist and chair of the LSU Chemistry Department.

Amphiuma are one of the only amphibian species thriving in a crisis that is currently affecting their cold-blooded frog and toad friends. Research into their “slime” may hold the key to understanding how amphiuma resist certain skin diseases. This research may help the amphibian population and perhaps humans, too.

The rapid decline of amphibian populations is now categorized as the Earth’s sixth mass extinction. Biologists have seen declines in more than 500 amphibian species and 90 extinctions over the past 50 years, and the problem is growing.

“The amphibian populations are just crashing around the world,” Pojman said. “There were theories—was it pesticides or ozone holes—but no, all of those played some role, but the main thing was this fungus that is spread by pets, by the pet trade.”

The fungus comprises two types of fungal pathogens called Batrachochytrium dendrobatisis (Bd) and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal). These two pathogens cause the lethal skin disease, Chytridiomycosis, which is a cause for the mass regressions in amphibians.

With any fast-spreading disease, finding a cure can seem like a daunting task and sometimes even unattainable. However, with this particular skin disease, the cure may not be so far away; it may even be in LSU’s own backyard.

LSU alumna and scientist Kenzie Pereira said the difficulty in fighting an emerging disease is the gap of knowledge between the known and the unknown, whether in human or wild animal populations.

“If you don’t know what the important factors are that can contribute to the infection of a given pathogen causing disease, or if you don’t know how the disease spreads or who’s going to get it and who’s not going to get it,” Pereira said. “There’s no way that you’re going to be able to control it.”

These three-toed amphiuma are unique among vertebrate classes as they contain two distinct types of glands: mucous and granular. The granular glands are more frequent in the lower body areas, which were found to possibly possess specified functions.

In addition to being a unique part of the Southeastern U.S. aquatic ecosystem, these creatures have a secret, and it’s in their slime.

“We found that the slime killed this fungus that is wiping out amphibians around the world,” Pojman said.

The Bd pathogen has been studied for many amphibian species, but the Bsal pathogen has a lack of research surrounding it.

The fungus infects the host and entrenches and matures within the skin of the animal, manifesting and killing the organism.

In a study that’s the first of its kind, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology in April 2018, scientists studied adult male and female amphiuma and tested against Bd and Bsal.

They discovered that they both inhibited the growth of such fungi. This means that the same skin secretions that protect against Bd may also protect against Bsal.

The antimicrobial secretions from these creatures are particularly interesting because they essentially form a shield with their slime, limiting the potency of the fungal pathogens before they develop into the deathly skin disease.

In the same article on salamander’s skin glands, a sample of 55 amphiuma was tested for the presence of Bd, and although 23 of the amphiuma that were tested, were infected with Bd, none of them showed any symptoms of the skin disease. This suggests that the slime may serve a protective role against skin disease.

The research surrounding the efficacy of skin secretions in the three-toed amphiuma, although limited, is heading in a positive direction to understanding the species’ immune defenses against fungal pathogens, which are linked to the worldwide amphibian decline.

“One of the benefits to studying one of the microbial properties of skin secretions against the fungus of this particular species is because it’s a way to figure out how this species can cope with different pathogens in the environment,” Pereira said.

“So if we find out that these skin secretions have this really potent properties, then maybe these skin secretions are one of the reasons why this particular species doesn’t become infected or die from the disease.”

The emerging studies on salamander slime and the out-of-the-box thinking involved in this type of research are changing the thought processes in how to possibly protect other individuals from this skin disease in the future.

The next step in this process is to conduct further studies to narrow down the reasons for the unique properties of the salamander slime. The more information gathered the more of an understanding can be developed.

“The strange thing is that while amphibian populations are crashing,” Pojman said, “these animals are not only thriving, but they are immune to it.”

Solution to global amphibian decline possibly lies in LSU’s backyard through native salamander research

May 7, 2020

Dr. John Pojman, chair of the LSU chemistry department is holding his favorite coffee mug which reads, “got amphiuma?”. The saying is based on the famous advertising campaign, “got milk?”, by Goodby Silverstein and partners that have circulated the internet since 1993.