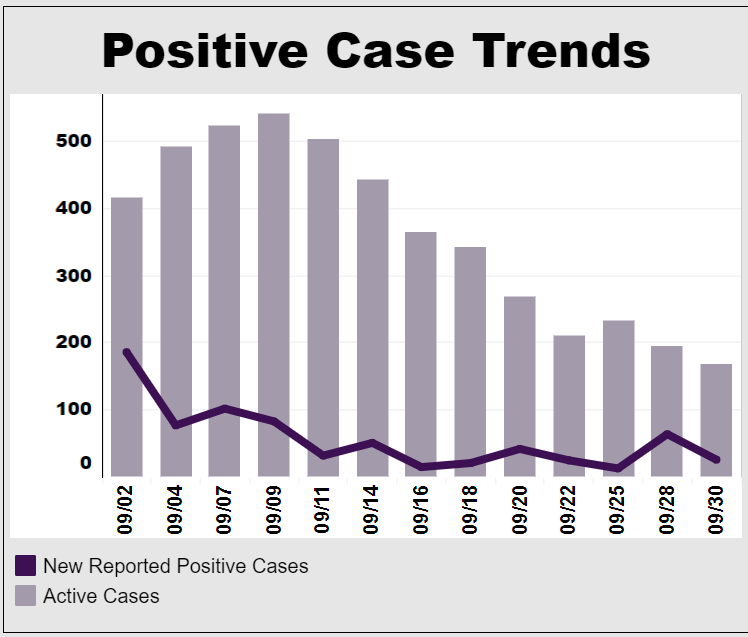

1,015 cases. 46 days. We can’t say we’re surprised.

While institutions across the country grappled with the decision of whether to resume in-person activities in the fall, the University made its intentions clear as early as May 7.

“Things may look a little different,” Interim President Thomas Galligan warned students in a May 7 email, the first to definitively announce the campus reopening, but “it is our intention to have campus open and return to in-person, traditional classes this fall.”

There was never a question that students would return to campus in August; the real question was how long they would be allowed to stay. With each passing day, it becomes clearer that the University’s stance on a remote transition can be summed up in three words: “we don’t blink.”

Even in the face of high-profile failures, including University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s hasty return to remote instruction just days after reopening its doors, LSU trudged forward with the “Roadmap to Fall 2020” as its guide. Now that the initial wave of campus closures has subsided, the University’s campus will almost certainly remain open through this semester. It can’t afford not to.

The University lost $27.73 million in revenue and incurred $5.57 million in COVID-19 expenses after the pandemic hit, according to Executive Vice President for Finance and Administration & CFO Dan Layzell. This comes after the University suffered an $8.9 million loss of state funding this year, a 7.5% reduction from 2019.

It simply didn’t make financial sense for the University to continue its remote operations. Now that football season has started, the primary breadwinner of the $157 million LSU Athletics brings into the University every year, students should be sure they packed their winter clothes.

While a fully remote semester would have been the safest option, and it hasn’t implemented a foolproof reopening plan, University administration is concerned with students’ wellbeing. The administration doesn’t want the number of COVID-19 cases to continue increasing; even from a strictly business standpoint, it must consider this untraditional semester’s effect on the University retention rate.

The University’s goal is to have the safest on-campus experience possible. Where it falls short of that goal is its failure to be fully transparent about the quality of the benchmarks it’s using to measure its progress and the actions it will take should it not meet those benchmarks.

The University has repeatedly stated that students who fail to comply with COVID-19 procedures will be “referred to Student Advocacy and Accountability for violating the Code of Student Conduct.” What specific actions will SAA take to address these violations?

The lack of a mandatory testing system makes the daily symptom checker a primary indicator of the number of suspected or confirmed cases at the University. Why are there no consequences for not completing the checker, especially for those who are on campus every day.? Are there consequences for lying about your symptoms? Are there consequences for returning to campus without receiving approval from the checker?

The University has the resources to perform 5,000 tests a day but has only performed 6,290 total tests as of Sept. 30. However, it likely anticipates that number to increase as students who have taken a COVID-19 test after Aug. 15 receive priority consideration for football tickets.

Students will only make up about 2,500 of the 25,000 fans at each football game; why are they the only ones being incentivised to receive a test? What good does an Aug. 15 test result do a student hoping to attend the Oct. 10 game against Missouri? Even if all 2,500 students at a game are tested, they are being put at risk by the other 22,500 fans who may or may not have been tested.

This week, the University instructed students living in certain “high risk” residence halls to receive mandatory COVID-19 testing at designated times in their rooms. Why is the University refusing to announce the locations of these high-risk areas? Can “student privacy concerns” really be cited when universities like UNC have been reporting the specific case numbers in residence hall clusters since August?

The University listed several factors, including the symptom checker and wastewater testing, it used to identify its high-risk areas, but is there a specific threshold that warrants a high-risk classification? Should these halls expect regular testing until they are no longer deemed a high-risk area?

Clearly, there are a lot of questions the University has left unanswered.

The Reveille will continue to work on finding the answers to these questions, but the University is doing students a disservice by leaving them in the dark on so many areas of its COVID-19 response plan.

Cases have steadily increased since students arrived on campus. While the University made the decision to reopen campus, the blame doesn’t solely lie with the administration. We all share the responsibility of following the COVID-19 protocols and doing our part to stop the spread.

But as the state’s flagship campus, the University carries a higher burden. It must not only take into account student safety but also the safety of faculty, staff, the Baton Rouge community and the state at large, which are all impacted by its decision to reopen campus. Even if the University does everything possible to monitor COVID-19 cases within the LSU community, there is no way it can ever measure the full impact of its reopening on the greater community.

That’s what makes transparency so important. Only when the University provides more specific information regarding its COVID-19 response can the LSU community remove its rose-colored glasses and become more involved in the efforts to make our campus and community safer.

Tiger Stadium shines bright Tuesday, Sept. 15, 2020 at night on N Stadium Road on LSU's campus.