Corporate money flows through Washington, D.C. like a sewer system, soiling even the most idealistic politicians and corrupting them into little more than a career fundraiser catering to special interest groups. Don’t be fooled by deceptive campaign promises to “drain the swamp.”

Members of Congress on both sides of the aisle can spend over four hours a day soliciting donations from wealthy donors in off-site call centers just blocks away from Capitol Hill. That’s twice the number of hours spent on telemarketing instead of doing their actual job.

As former Rep. David Jolly, R-Florida, explained: it comes down to the importance of fundraising in winning reelection. To get re-elected, members of Congress need to raise millions not only for themselves, but also for dues for their respective parties. Former Rep. Steve Israel, D-New York, who was in charge of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, sees the problem as systemic, stemming from the Supreme Court’s decision in the 2010 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case. Since then corporations, individuals and unions have been able to donate an unlimited amount of money to campaigns as a constitutionally protected form of political speech, which was controversially extended to corporations too.

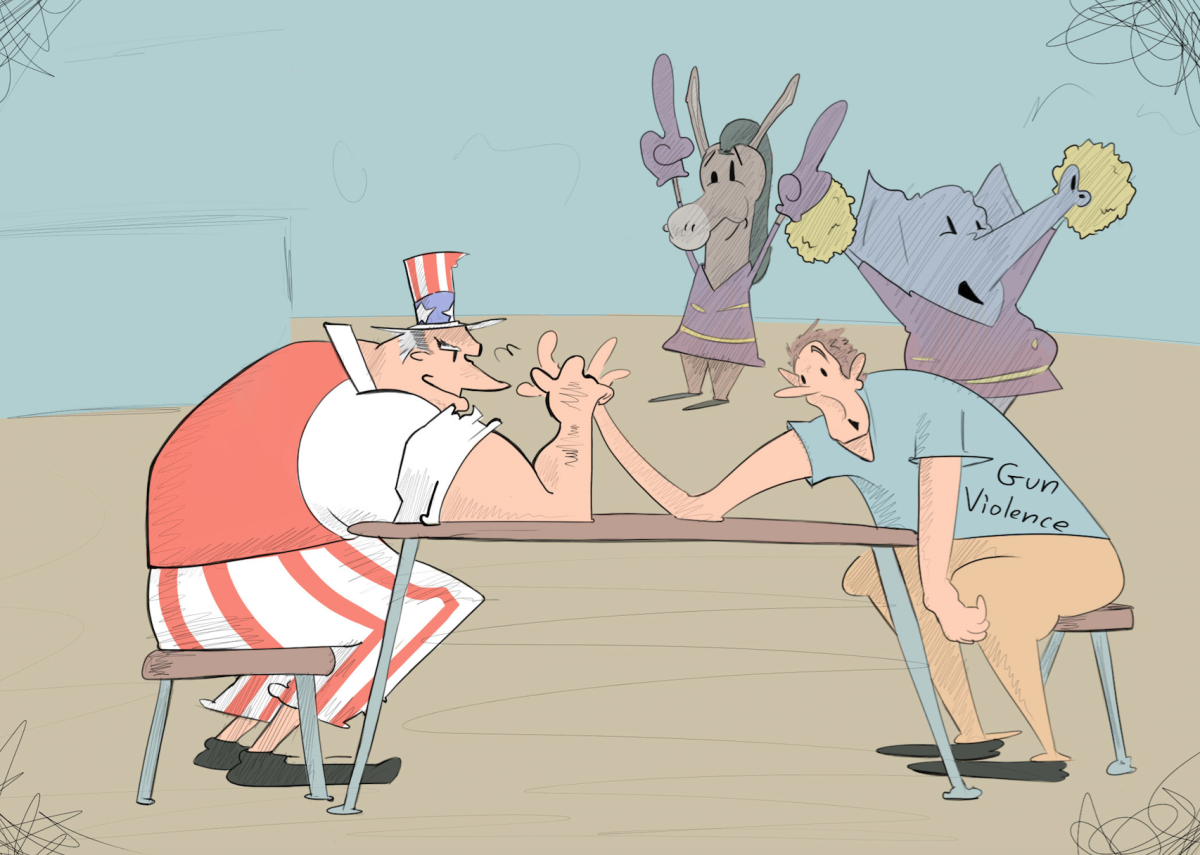

This has put an ever higher amount of pressure on elected officials and political parties to fundraise in what has become an “arms race” to stuff campaign war chests with as much money as possible.

While Republican and Democratic voters don’t agree on much these days, there is a growing consensus that our political system is broken, and that an outsized influence of corporate and wealthy individual donations has rigged this system.

The displacement of blue-collar jobs due to automation and globalization, for example, goes unnoticed when elected officials prioritize special interests over public interests. Corporate profits soar with lower labor costs, and so the stock market rallies and quarterly GDP growth projections increase. Yet, while elected officials are cashing checks from corporate and wealthy individual donors, displaced blue-collar American workers struggle to reenter the workforce with weak social safety nets and without adequate job training available for career transition.

Blue-collar displacement is just one of a long list of government actions in favor of special interests and to the detriment of the average Americans. For Democrats and Republicans alike, the government’s handling of the 2008 financial crisis was the most telling moment of whose side elected officials were on.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the federal government shelled out trillions in taxpayer money to bailout the financial sector, only for banks to turn around and successfully lobby against regulation and issue tens of millions in executive bonuses. Only one small-time investment banker was sentenced with most other convictions resulting in a slap on the wrist to the tune of millions in legal fines — barely noticed in the footnotes of corporate financial disclosures.

The message is clear: white-collar criminals are above the law, welfare only has bipartisan support for large corporations and everybody else has to pay for their hubris.

Thus, in rebuke of an “elitist” establishment out-of-touch with the struggle of ordinary working class Americans, so called “populist” candidates have been winning elections across the country. Every campaign is now “grass roots” and every candidate a “political outsider.”

In retrospect, it’s no surprise how in the 2016 presidential election then-candidate President Donald Trump could tear down the blue wall in the Rust Belt where Democrats had won. Likewise, it is no surprise how in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary, despite the Democratic National Committee’s best efforts, long-shot populist candidate Bernie Sanders could get 43 percent of the popular vote to Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s 55 percent.

But, with the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling providing a virtually ironclad legal defense for unlimited campaign funding by corporations and wealthy elites, all hope seems lost for much needed comprehensive campaign finance reform.

Thus, it is equally unsurprising that the president who ran on “draining the swamp” has also appointed many industry lobbyists to regulatory positions. One example is Trump’s recent nomination of Andrew Wheeler, a former coal lobbyist, to be head of the EPA, which illuminates the corruption in government and the power disparity between corporate lobbyists and American voters.

Regulatory legislation has either been substantially shaped by special interest groups or outright halted.

Unless, of course, there’s a foreign terrorist attack, in which case Congress would draw up and pass legislation within weeks, and in less than two months the president would sign it into law. I’m referring to the USA Patriot Act, and I haven’t otherwise witnessed such a swift legislative process for public interest legislation. It hadn’t happened after the financial crisis of 2008; it hadn’t happened after the BP oil spill; and, it hadn’t happened after the Sandy Hook Elementary school shooting, even after the long list of mass shootings that have happened since.

There aren’t any K-Street lobbyists working on behalf of foreign terrorist organizations, but there sure as hell are for domestic investment banks, oil companies and gun manufacturers.

The callousness is justified after two years of a Trump presidency that didn’t involve a “draining of the swamp,” but a deepening of what has become a cesspool. Special interests are seemingly more represented in Trump’s administration than in any other in modern U.S. presidential history — a much soberer parallel to former president Ulysses S. Grant’s administration. Trump is less so akin to the much more progressive Teddy Roosevelt, but this country needs him to be now more than ever. I wouldn’t hold my breath, however, for changes to a broken political system during this administration or the next.

Patrick Gagen is a 21-year-old mass communication and finance senior from Suwanee, Georgia.