Due to the intense lobbying efforts of religiously affiliated groups, in 1920, Congress ratified the Eighteenth Amendment banning the “manufacture, sale and transportation of intoxicating liquors.” Fervent prohibitionists convinced politicians across the ideological spectrum that banning alcohol would reduce various societal issues, such as poverty and violence. Former President Herbert Hoover dubbed the prohibition of alcohol to be the “noble experiment.”

However, the experiment utterly failed, and Congress passed the Twenty-first Amendment repealing the prohibition of alcohol only 13 years later. By 1933, alcohol consumption, violent crime and prison population had all increased. Furthermore, it deprived the federal government of much needed tax revenue amidst the Great Depression.

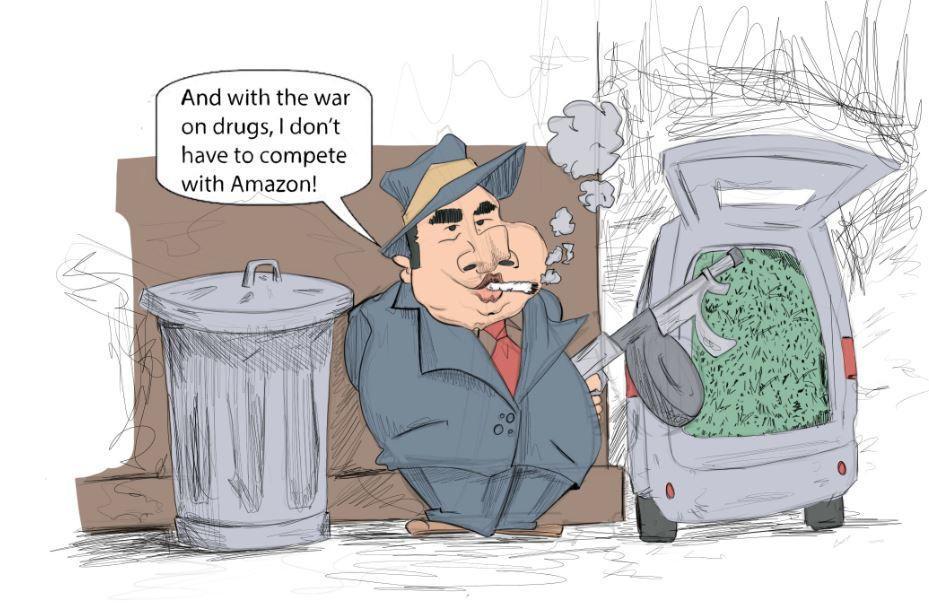

Basic economics offers a simple explanation for why the war on alcohol produced such bad outcomes. The ban curbed the legal supply of alcohol, but market demand remained high. Thus, because demand remained high, a black market supply emerged to meet demand and achieve equilibrium.

This black market supplied illegal alcohol at artificially high prices, which made it a very lucrative business for organized crime. Then-notorious and now romanticized gangsters, such as Al Capone and ‘Lucky’ Luciano, murdered their market competitors and paid off corrupted cops and politicians. They fought violent territorial wars that spiked the rate of homicides, assaults and burglaries.

One might think America had learned its lesson. Morality laws, such as alcohol prohibition, create unintentionally bad outcomes. However, in 1971, former President Richard Nixon declared, “America’s public enemy number one is drug abuse. In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive.” In spite of prior evidence to the contrary, Nixon and his Republican counterparts in Congress believed they could conquer the economic law of supply and demand by curbing the supply of drugs.

Thus, America became ensnared in a domestic quagmire as costly and ceaseless as the foreign war being fought in Vietnam. The only difference is that the war in Vietnam eventually ended, but the War on Drugs continued. Former President Ronald Reagan’s administration implemented a novel approach to the War on Drugs by attempting to prevent both the supply and demand of drugs. Reagan expanded the war on drugs into foreign countries, and with the passage of his 1986 crime bill, implemented the mass incarceration of drug offenders — the effects of which made the U.S. the most highly incarcerated country in the world.

Despite spending over a trillion dollars and incarcerating over half a million Americans, many states and cities are still rife with drug usage and violent crime. Individuals and communities have yet to fully recover from the failed drug policies of the past four decades.

Recently, public policy makers have rolled back the most damaging effect of the “moral” War on Drugs: incarceration. Louisiana, for example, used to have the highest incarceration rate in the country, but because of prison reform led by Gov. John Bel Edwards, small-time drug offenses are slowly being decriminalized and offenders are receiving better treatment.

While morality laws are well-intentioned, they don’t prevent behavior from occurring. In fact, the prohibition of both alcohol and drugs actually increased substance use and violent crime. Whether it’s a war on alcohol, drugs or any other vice, a legal ban will always create an illegal supply. Economics is not suspended for morals; thus, morality laws are poor policies.

Patrick Gagen is a 21-year-old mass communication and finance senior from Suwanee, Georgia.