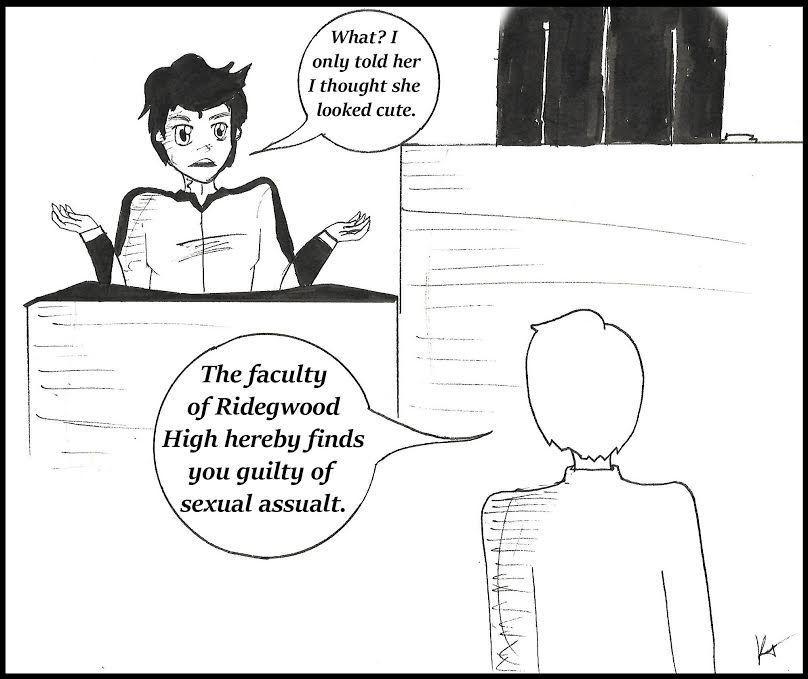

There are a few things the University’s disciplinary system is good at handling: fraternity pranks, inter-club disputes and plagiarism. But one thing it shouldn’t touch before a court has the chance to look at is accusations of sexual assault.

These claims are some of the most serious charges a person can face. When somebody is charged as a rapist, their life changes forever. People will shun them, hide their children from them and refuse to give them jobs.

All of those things are good if the person actually committed the crime. However, if the accused did not sexually assault the victim, the accused’s name will be dragged through the mud for something they didn’t do.

To be clear, lawmakers and university administrators should take all reasonable means to ensure victims of sexual assault are taken seriously and the crimes are prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. However, let’s not pretend every person who reports a sexual assault is telling the truth.

The national flash point for this was Rolling Stone’s University of Virginia rape story, whose poster child and main source, known only as “Jackie,” was widely discredited by every outlet from Reason to the Columbia School of Journalism.

“Jackie” will now have to testify for a defamation suit brought by a university administrator against the magazine, according to The New York Times.

“Jackie” didn’t report her assault, but if she had, the University of Virginia might have screwed her or her alleged attacker over. Both public and private universities are proving themselves inept at adequately handling sexual assault claims.

Take the case of a male student at the University of Texas at Austin, who had consensual sex with a female non-student. A team of investigators with the university’s Title IX bureaucracy still recommended he be expelled without having the chance to ask witnesses questions about the encounter, because the woman’s father filed a police report.

This is exactly the problem. The right to an attorney and the right to cross-examine witnesses is a fundamental component of due process that the school is denying him. If the school ends up expelling him, however, the student will have to go to court to start his education again.

Luckily, the LSU Code of Student Conduct allows students to call witnesses to testify. However, it doesn’t allow the student a lawyer to properly structure their case.

There is no easy solution to this matter. Sexual assault cases are messy beyond belief and almost impossible to prove definitively one way or the other. I do know one thing though: universities should not halt a student’s education before a court rules on the matter.

Not following this rule hurts both victims and the accused. If a university rules against someone and expels them, but a court overturns the decision for lack of due process, the victim is put on an emotional roller coaster that will only exacerbate his or her feelings of powerlessness.

And let’s be clear again: few people are qualified to appropriately handle sexual assault cases. Both police and university coordinators need to know how to be compassionate to the victim, while still upholding due process for the accused.

If the students need to stay away from each other, then the University should separate them. If one of the students is in danger, then the police need to be called. Universities should not prosecute violent crimes. Let the courts handle it.

Jack Richards is a mass communication senior from New Orleans, Louisiana.

OPINION: Universities should defer to the courts on sexual assault cases

By @jayellrichy

Jack Richards

April 5, 2016

More to Discover