Cleveland Avenue in New Orleans, nowadays the heart of Mid City, featured a block of Louisiana’s most polished and accomplished athletes in the late 1960s.

As all 1950-60s industrializing city-streets and neighborhoods were at the time, that block was small, barren, yet prospering.

Bob Pettit, a Baton Rouge High School alumnus, had just purchased a lot there to build his new home in the late 1960s. Across the way was former New Orleans Saints Pro Bowl cornerback Dave Whitsell. Next door to Whitsell was one of LSU’s finest former running backs and Pro Football Hall of Fame member, Jimmy Taylor.

Across the street from Taylor was Pete Maravich.

“We all lived within a block of each other,” Pettit said.

Fame neighbored Pettit after his storied basketball career just as it surrounded him on a day LSU basketball dedicated solely to him.

Pettit — joined by his 10 grandchildren, hundreds of friends, family members and former teammates — uncloaked a nearly 30-foot statue of himself on Saturday beside Pete Maravich’s Assembly Center.

The statue featured a moment of Pettit’s before scoring one of his 1,916 points collected as a Tiger — a silky-smooth, perfectly-formed jump-shot rendered in shiny bronze.

As humble and absorptive as he could be, Pettit stood in awe.

“I never dreamed in my wildest dreams that something could happen like that,” Pettit said.

Pettit was finally satisfied — an emotion never fully realized throughout his three seasons at LSU and 11 in the NBA.

“Number one, I liked it very much,” Pettit said. “I didn’t know I had that many muscles and that much hair, but I thought it was a great job.”

Pettit said he will be forever grateful for the new memorial to his legacy.

From the ground up, like the statue, his basketball career began unassuming. The pedestal of Pettit’s sculpture is blanketed in grey marble with his name etched in gold on a plain granite background.

As a sophomore hooper in high school, he was rejected for not being good skilled enough to make the team. His long, lanky, 6-foot-2 frame was attached to a set of woefully uncoordinated, veiny hands which wasn’t enough to benefit then-Baton Rouge High School coach Kenner Day in 1947.

But as he always has, Pettit didn’t accept rejection as conclusion.

He worked on his game and grew from 6 feet 2 inches as a sophomore to 6-foot-5, or 6-foot-6, his senior year, which he jokingly said, “helped.”

Pettit led Baton Rouge High to a State Championship victory in 1950 against St. Aloysius, which he said was “one of his greatest moments” in a storied career, including his days as a world-famous Tiger and NBA legend.

He knew of his special skill-set. He knew he had the gift to be great. But during his tenure at LSU, he had to study.

“Business,” Pettit said. “College of Commerce. I graduated in four years. How about that? That’s something to be proud of.”

To Pettit, it was, but his basketball career was the real reason the 83-year-old remained smiling on Saturday.

“Being from down here, you never realize where you’re going,” Pettit said. “I had ambition as a sophomore in high school, when I got cut from the basketball team, to win a letter. That’s all I wanted, just to win a letter. And here I am, with a statue. I’m very flattered. Did I ever dream it? No, never.”

Pettit, a 6-foot-10 forward at LSU from 1951-54, said his best attribute as a player was rebounding. He gathered 1,039 rebounds during his three seasons, and remains as LSU’s fourth-best rebounder in the program’s history.

But he could score, too. Pettit nearly mastered all phases of the game: defense, rebounding, scoring, work ethic, passion, pride and determination.

“I think what I did best was rebound,” Pettit said of his NBA career. “To toot my own horn, I think I’m the third leading rebounder in rebounds per game. Number one would be [Wilt] Chamberlain, or [Bill] Russell. Number two would be Bill Russell or Chamberlain.”

Like Russell’s 11 Championships and Chamberlain’s 100 points in a single game, Pettit was a record breaker.

He was only one of two Tigers to tally 60 points in a game for LSU. The other was Pete Maravich.

LSU retired Pettit’s jersey in 1954 — the same year he was selected as the second-overall pick to the Milwaukee Hawks in the 1954 NBA Draft.

Pettit received an $11,000 contract with the Hawks, the then-all-time highest salary for a rookie.

“I was very aware of my abilities,” Pettit said. “I was very aware of my limitations. I did everything I could. In 1956, I was voted MVP of the league, led the league in scoring, and lead the league in rebounding. That was a pretty good year, I’d say. But I came home and asked myself, ‘What can I do to get better?’”

Upon arriving in Baton Rouge during the offseason, Pettit would focus on improving one aspect of his game. One summer, it was shooting free throws, he said. Another was jump-shots.

Pettit, still a monster in height, needed to be able to “push, shove, claw and scratch” to become a better rebounder.

In the 1950s, there was only one person to reach out to for muscle-building in Baton Rouge. That was Alvin Roy, LSU football’s most influential strength and conditioning coach of all-time.

Roy trained Taylor and Heisman Trophy winning running back Billy Cannon during their tenures as Tigers. After Roy’s brief stint with the Army, Pettit — who said he was then “thin as a rail” — stepped to his door, requesting the muscles he’s now so appreciative of in his statue.

“I needed to be stronger,” Pettit said. “The pushing and shoving under that backboard, I’ll need to be stronger. So I went to see Alvin Roy right here on Oklahoma Street. I said, ‘Alvin, I need to get stronger, can you help me?’ He said, ‘Man, I’m the man. I can help you, and I’ll never make you to where your muscles will hurt or hinder you.’”

The owner of the Hawks at the time believed too much weight-lifting was counterproductive — “muscle bounding” as Pettit called it. After training with Roy, Pettit said he put on 30 or more pounds of muscle, which he said, “made a huge difference.”

“I was always striving to get better,” Pettit said. “I think that was an advantage. I was never happy. I was never satisfied, because I always looked for ways to get better.”

Pettit, a Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame member, was a one-time NBA Champion, reached 11 All-Star games, scored more than 20,000 points in the sport’s most competitive professional league and was a two-time league MVP.

Pettit, as he was introduced on Tuesday as “a legend,” was just that.

His influence as a Baton Rouge-born athlete continues to be colossal more than 60 years after his graduation, and Shaquille O’Neal — arguably LSU’s most popular alumnus, who has a neighboring statue of his own beside Pettit’s — couldn’t agree more.

“He said, ‘Mr. Pettit,’ in a very soft voice,” Pettit said. “‘Mr. Pettit. Do you know that somebody told me in the history of the NBA there was only three great players from one team? North Carolina. They were wrong. Because we had you, me and Pete Maravich.’ I said, ‘That’s exactly right.’”

You can reach Christian Boutwell on Twitter: @CBoutwell_TDR

LSU basketball legend Bob Pettit immortalized with statue

By Christian Boutwell

February 28, 2016

Emily Brauner

LSU basketball legend Bob Pettit is honored with a statue unveiled Saturday, Feb. 27, 2016 in front of the PMAC.

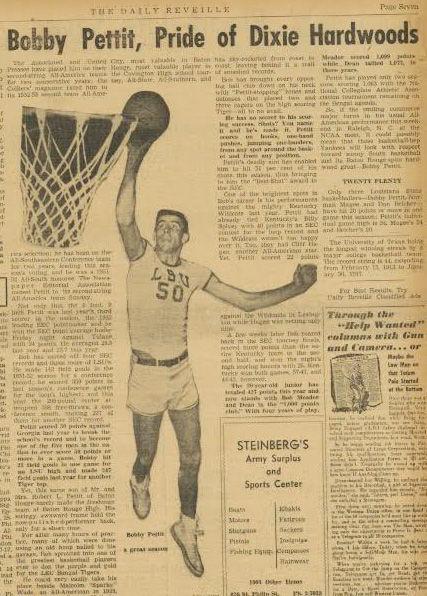

The Daily Reveille Vol. 57, No. 71 on Tuesday, March 10, 1953, featuring LSU basketball legend Bob Pettit

More to Discover