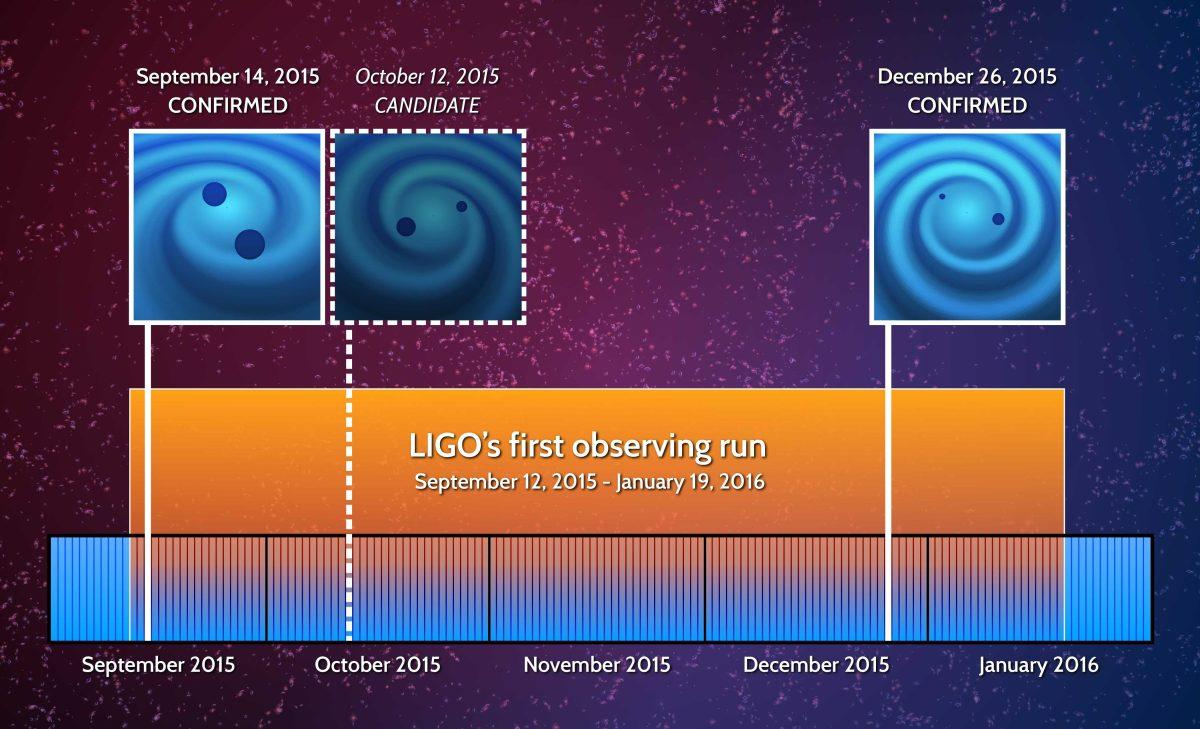

The Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatories in Livingston and Hanford, Washington have discovered gravitational waves for the second time.

The discovery was made Dec. 26 when both detectors identified gravitational waves following the merger of two black holes approximately 1.4 billion years ago, according to a press release from the LIGO Scientific Collaboration. The merger resulted in a single, spinning black hole 21 times the mass of the sun.

This second merger is less massive than the initial observation announced on February 11. The lesser mass allowed scientists to observe the waves for approximately one second, said University professor and LIGO Scientific Collaboration spokesperson Gabriela González.

University assistant professor of physics and LIGO contributor Thomas Corbitt said this second discovery is an important step in affirming the validity of the group’s initial findings.

“This gives us a lot more confidence that what we saw was not some kind of fluke,” Corbitt said.

Corbitt said the second observation is a positive step toward understanding more about the universe’s scientific unknowns and further confirming Einstein’s general theory of relativity. As more gravitational wave observations are made, LIGO scientists can better understand how many otherwise unobservable systems exist in the universe, he said.

With the LIGO detectors optimized to reach 1.5 to two times more of the universe’s volume this fall, Corbitt said scientists expect to see double the number of gravitational wave events observed in the initial data run. The increased sensitivity may also make it possible for scientists to detect more varied events, such as neutron stars or supernovas, he said.

In addition to increasing the number of events observed, the increased sensitivity can help LIGO scientists better determine the location of these astronomical events. By determining the source of these gravitational waves, Corbitt said the LIGO team hopes to observe the gravitational waves’ corresponding electromagnetic events.

The localization will be further improved when LIGO’s European partner, the Virgo Collaboration, joins the two LIGO detectors in collecting gravitational wave data later this fall, he said.

For Corbitt, who has worked on stages of the LIGO project for 15 years, this second detection marks the beginning of a new phase in the project.

“To me, the big thing that this signifies is that we are transitioning into not being just a gravitational wave project, but we’re transitioning into being astronomers and astrophysics,” Corbitt said.

On Wednesday, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration confirmed the detection of a second gravitational wave event. On Feb. 11, the group made history by confirming Einstein's theory of general relativity with their initial Sep. 14 detection.