There were no classes Thursday morning.

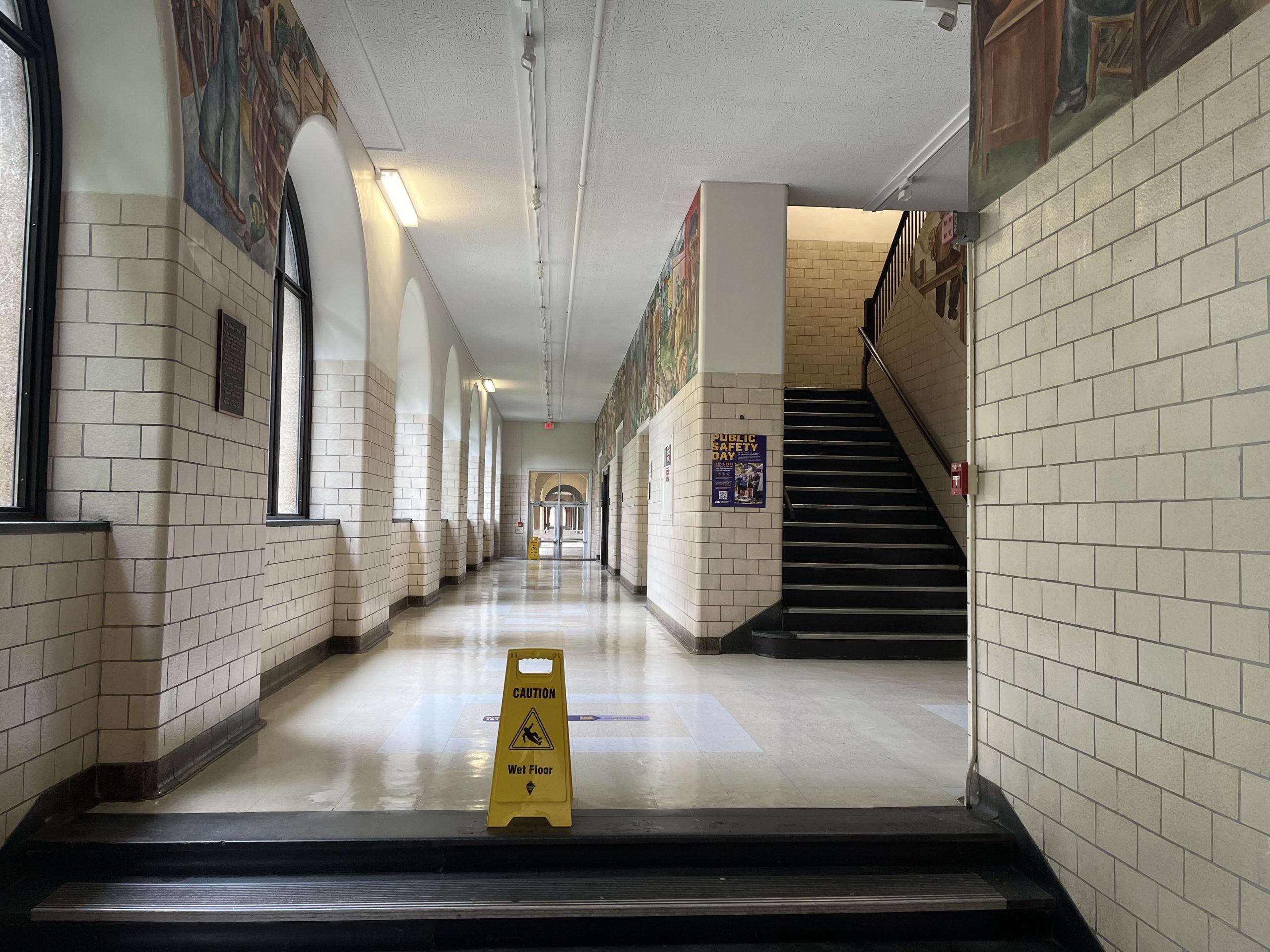

LSU’s corridors and quads were populated only by muddy puddles and debris from the canopies of the resident stately oaks.

A few young souls cloaked in oversized hoodies and baggy sweatpants made their ways to the university’s dining halls. But just a few; the rest were either sleeping in or had evacuated.

They weren’t wading through standing water in rubber boots, clutching ponchos against heavy wind or bracing umbrellas to keep dry. Their eyes were instead glued to their phone screens as slippers flopped against the pavement. Some were still hungover, with the smell of liquor on their breath from partying the night before. The weather was pleasantly cool albeit humid.

A short 48 hours before, experts and officials had forecasted Baton Rouge directly in the crosshairs of a mighty Category 2 hurricane, candidly named Francine.

How we got here

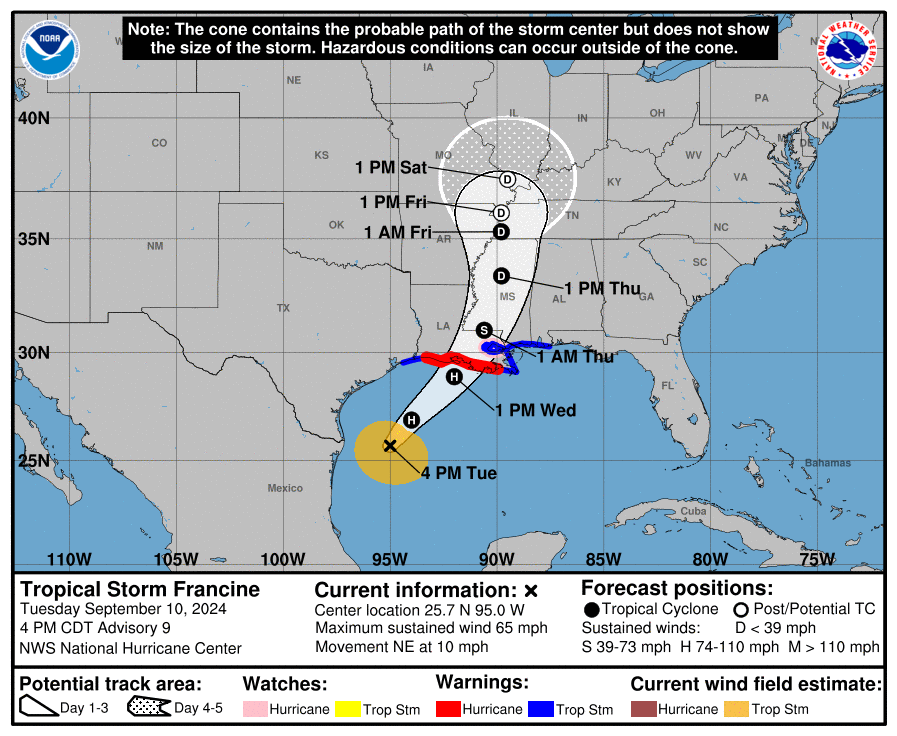

Francine, on Monday just a newly named tropical storm, was predicted by the National Hurricane Center in Miami to land on Louisiana’s west coast near the Lake Charles-Lafayette region. Subsequent forecasts increasingly shifted Francine’s landing eastward.

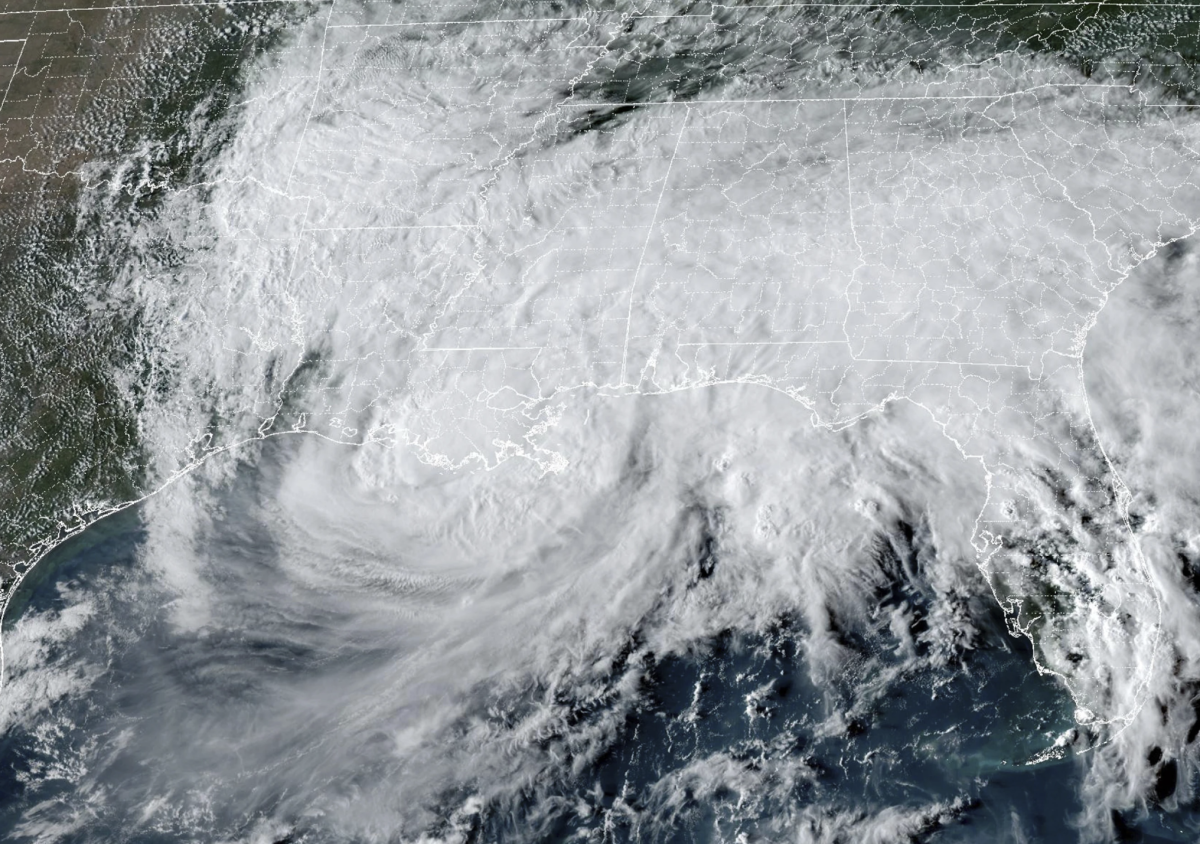

By the time Hurricane Francine made landfall in Louisiana Wednesday evening, it was at Morgan City. The hurricane crawled north and lashed the Crescent City with 8 inches of rainfall, winds that reached 80 miles per hour and moderate flooding.

Francine’s status was downgraded the further north it climbed. It was a tropical depression by the time it reached central Mississippi.

Over 400,000 Louisiana residents were left without power in the hurricane’s aftermath, most of them concentrated in the greater New Orleans area, River Parishes and Northshore.

Gov. Jeff Landry said at a Thursday morning press conference he wasn’t aware of any fatalities from the storm. President Joe Biden had declared a state of emergency for Louisiana at the Louisiana governor’s request.

“East Baton Rouge Parish was largely spared the greatest impacts of this storm,” said Mayor-President of Baton Rouge Sharon Weston Broome at a Thursday morning press conference. “And for that, we are extremely grateful.”

Her sentiment was shared by many of LSU’s residents.

Over 10,000 were without power in Baton Rouge the morning after Francine.

Classes and offices at LSU would resume as normal on Friday. The university closed campus and moved to virtual learning Wednesday and Thursday anticipating the storm.

This was done in an effort to prevent makeup days in the future.

Remote classes were supposedly held Wednesday but the university canceled them for Thursday.

The university announced a shelter-in-place order for residents from Wednesday morning to Thursday afternoon. The order was lifted earlier than originally planned on Thursday morning.

The dorm-bound hurricane experience

Mathematics freshman Samuel Patten expected worse from the storm. In the end it was just a matter of waiting it out so he could go back outside.

“The dorms kept power, air conditioning was still on, lights were still on,” he said. “Everything was all right. It wasn’t as nearly as bad as it could’ve been.”

When students realized the storm was of little worry, he said, many took to partying.

“I honestly couldn’t hear the storm, the rain or wind or anything,” Patten said. No louder than his neighbors, in any case.

“I thought more would happen,” said kinesiology freshman Khylie Black. She said it was the first time she, a California native, experienced a hurricane.

She’d expected, before the hurricane, felled trees with branches littering the pathways and pools of standing water.

She said half of her hall fled campus to take shelter at home.

Victoria Ludwikowski, a marketing freshman and native New Yorker, said it wasn’t her first hurricane. Compared to Hurricane Sandy, she said Francine was anticlimactic – not that it’s a bad thing.

She spent most of the storm watching television.

When much of her building got bored, residents scurried to the common spaces and stayed up late playing cards.

She was joined by business freshman Brynn Yaple, a native of Mandeville who remembers being out of grade school for two weeks because of Hurricane Ida.

Yaple and Ludwikowski said they’d both weathered worse storms that were completely unnamed. Just the aftermath of Ida, Yaple said, was worse than Francine.

Ludwikowski said the campus was eerily quiet the morning after. Save for the dining halls and occasional groundskeeper, there were hardly any signs of life, she said.

“It was so boring,” she said. “We just had to get out of there.”

They agreed that it seemed like the storm was forecasted to be worse than it was.

“They said it was going to be this big storm,” said communications freshman Tania Herndon. “But what I saw was just regular rain. It was pretty chill for the most part.”

The power went out “for like two seconds,” Herndon added, who evacuated campus to a nearby Baton Rouge neighborhood. Hailing from Washington, D.C., she said it was her first hurricane.

“It wasn’t even like a hurricane, I think,” said Jayne Carter, a psychology freshman from Washington who said Francine was also her first hurricane.

Carter was glad to see a lack of flooding, let alone lack of puddles around campus upon returning Thursday midmorning.

Herndon said the university’s communication was lacking regarding campus’ closing. She was disappointed, she said, that at one point the university had announced its intention to stay open while simultaneously telling students and residents to stock three days worth of food and water.

She believes some of the messages sent out by the university were inconsistent and untimely. She compared LSU’s announcements to Southern’s which had made plans to cancel classes about a day before LSU did.

“There wasn’t much they could really do,” Herndon said. “But there could’ve been better protocol and communication about closing. Everything was so last minute.”

Carter said everything fell into place as it should’ve been.

“It’s cool,” she said. “As long as we got our free day, I don’t really care that much.”