Editor’s note: This article is among many featured in the Daily Reveille’s memorial issue commemorating the 50th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. For all of the Daily Reveille’s coverage, visit www.lsureveille.com/jfk

Jesse Walker was a young LSU professor looking at samples in his lab. For him, it was a normal day marred by bad news.

But for Raymond Strother, an Associated Press reporter in Baton Rouge and LSU graduate student, it was the day that dimmed his hopes for America. Strother looked up to President John F. Kennedy as a leader who represented his young generation.

Today marks the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination, one of the most tragic incidents in the nation’s history.

The generation of college students today never cheered on the handsome, young president. Millennials weren’t alive to feel the pang of the bullet that shot through Kennedy’s head and pierced America’s heart. But the stories about JFK, his “Camelot” era in the White House and the day when everything changed have filtered down through students’ parents, professors, coaches and bosses.

LSU lacks a definitive account of how campus reacted to hearing the news of the president’s death on Nov. 22, 1963. Archives come up empty for records of statements from the Board of Supervisors and the Office of Public Relations, according to Assistant University Archivist Barry Cowan. But those who were in Louisiana remember the sense of mourning that transcended the nation.

“It was like life stopped at that point,” Strother said.

Kennedy was visiting Dallas and riding in a motorcade downtown, his wife by his side, when he was shot in front of hundreds. Lyndon B. Johnson, his vice president, was immediately sworn in as his successor. A famous photo captured the freshly widowed Jacqueline Kennedy, still wearing her iconic pink Chanel suit, standing next to Johnson as he was sworn in to the presidency.

Police captured Lee Harvey Oswald, the alleged shooter, at the Texas Theatre. Oswald had also killed Dallas Police Officer J.D. Tippit shortly after killing Kennedy.

On Nov. 24, police were transferring Oswald to the county jail when Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby shot and killed him. Without a trial to convict Oswald, the slew of unanswered questions grew and ignited a storm of conspiracies.

The Warren Commission was formed to investigate Kennedy’s assassination. Its hotly contested 1964 report named Oswald as Kennedy’s lone assassin. The report claimed Oswald acted alone and killed the president with a rifle from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository.

Fifty years later, the image of JFK has morphed from a struggling first-term president to a glittering example of leadership.

But the American public has stayed much the same, according to Strother.

“The 50th anniversary comes at a critical point in history because we can see history repeating itself,” Strother said. He referenced the vitriol and controversy surrounding President Barack Obama.

SADNESS AND CELEBRATIONSWalker and Strother had opposite experiences in Baton Rouge on the day Kennedy was killed.

Walker, a professor in the University’s Department of Geography and Anthropology , was looking at samples from Alaska with a Swedish researcher in his lab. Around 1 p.m., someone came into the lab and announced the news. Walker turned on the radio, where it was confirmed.

The news was a shock, but he went back to work soon afterward.

“I don’t recall anything about the mood on campus,” said Walker, now a 92-year-old, highest ranking Boyd Professor who still does research for the University. “We worked that afternoon — we continued doing what we were doing.”

But it wasn’t work as usual for Strother. As a Kennedy fan and now famous Democratic political consultant, Strother heard the news of his president’s death in a brutal way when he arrived at an interview.

“Did you hear the great news?” someone asked him. “They killed the bastard.”

He felt a blow to his whole body. He remembered people in Baton Rouge celebrating the death of the man who they hated and he loved.

“I simply gave up on America for a while,” he said.

Strother didn’t go to classes. He doesn’t remember writing a front-page story in the next publication of The Daily Reveille. He doesn’t know why he didn’t attend LSU’s memorial service.

What Strother does remember is retreating to a friend’s apartment for the next three days. They watched a small black-and-white television. Glass after glass of scotch fueled them through it.

The Daily Reveille published a special JFK memorial issue on Nov. 26, 1963. Black wreaths adorned the top of the newspaper.

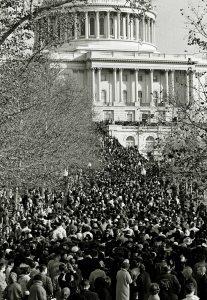

The news editor, Charles McBride, covered the funeral from Washington, D.C. He sent in a first-person narrative but never returned from the nation’s capital, where he moved, Strother said.

“I am not a flag-waver, not a super-patriot, but I felt — just as almost every other American felt at that moment — very proud that the flag draping the mahogany casket was mine,” McBride wrote in the Nov. 26 edition.

ONE STATE OVER

Louisiana played its own role in the aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination. Oswald was born in New Orleans and lived there in 1963. Judith Baker, who claims to have been Oswald’s lover, told an audience last month at Loyola University that Oswald loved the city and that people should be suspicious of the events surrounding Kennedy’s death.

In 1967, a New Orleans man named Clay Shaw was arrested for a connection to Kennedy’s assassination. Shaw was a homosexual businessman. The New Orleans District Attorney’s office booked him with a conspiracy charge to kill the president.

The jury quickly acquitted Shaw at his 1969 trial, but the event dragged the JFK saga into Louisiana as well.

Alecia Long, LSU history professor, said Kennedy’s push for civil rights actually helped Shaw years later. Shaw filed a civil rights lawsuit against the man who prosecuted him — Orleans Parish District Attorney Jim Garrison. Kennedy’s civil rights movement is often known for its racial base, but it also paved the way for gay rights, Long said.

Long doesn’t agree with conspiracy theories. She believes Oswald acted alone. Everything she teaches about Kennedy and the assassination is grounded in fact, she said.

One of the most common misconceptions about Kennedy is that he was always a beloved president, Long said. Instead, he was a struggling first-term president who barely won the election.

“I would not over-romanticize Kennedy even though he’s a romantic figure,” she said.

The 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination is a time when Long wants to remember the president’s contributions to the country and to the civil rights movement.

“We can keep it as a placeholder for great American tragedy, and it certainly is that, but I don’t think that’s how Kennedy would want us to look at it,” she said.

A COUNTRY THAT HASN’T CHANGED, BUT ALSO HASN’T FORGOTTENThe American public’s distaste and disrespect toward Obama today is similar to the attitudes directed at Kennedy 50 years ago, Strother said.

“Rather than a rebirth of hope or change, nothing has happened,” he said.

Had the assassination occurred in today’s society, Strother doesn’t necessarily think the grief and heavyheartedness would have been as intense.

“Today, we’ve had so much violence, so many bad things — you could probably shrug it off better,” he said. “Then, there was a feeling of invincibility.”

That feeling burst on November 22, 1963. The difference in America has lingered ever since, as evidenced by the bevy of books, documentaries, ceremonies, news stories and presentations about Kennedy.

The country still remembers.

“In some ways, none of us ever returned to the same place we were before the assassination,” Strother said. “Some memories pierce the soul, and it never completely scabs over.”