Every Thursday afternoon, students in dairy science professor Chuck Boeneke’s class don hairnets and stir pots to make a variety of foods — and they all begin with milk. Their most recent creation: cottage cheese.

Boeneke said students in his dairy foods technology class —ANSC 4020 — learn about dairy processing procedures that they apply in their lab. They cover topics such as sanitation, pasteurizing, the role of fats and milk solids and how to make low fat versions of products. Students use both computer and long hand calculations to formulate recipes.

In the lab portion of the class, students make products such as cheese, yogurt, buttermilk, sour cream and ice cream using milk from cows at the LSU AgCenter’s dairy farm. Later this semester, the students will make a 1,000-gallon batch of cheddar cheese to be sold in the LSU Dairy Store, Boeneke said.

The class gives students an opportunity to turn what they learn about in class into something tangible. Boeneke said it is a unique experience to taste foods you made, knowing exactly how it got to that stage from the microscopic level.

“I don’t guess they realize how much stuff goes into making the products and whenever they really start to see, it’s like, ‘Wow, I didn’t realize there was that much stuff that was involved just in processing milk,’” Boeneke said.

The class, which has 17 students, is open to all majors. Boeneke said learning how food is made and where it comes from is important for everyone because “you never know where you’ll use it.”

Boeneke said today’s food industry does significant amounts of research and development, especially related to flavor chemistry — making new flavors that taste just right so they are sellable — and adjusting fat content, homogenizations and cultures for better nutrition, texture and taste. That makes it important for anyone in the industry, whether they make or market products, to know what has to be changed to respond to consumer demands, he said.

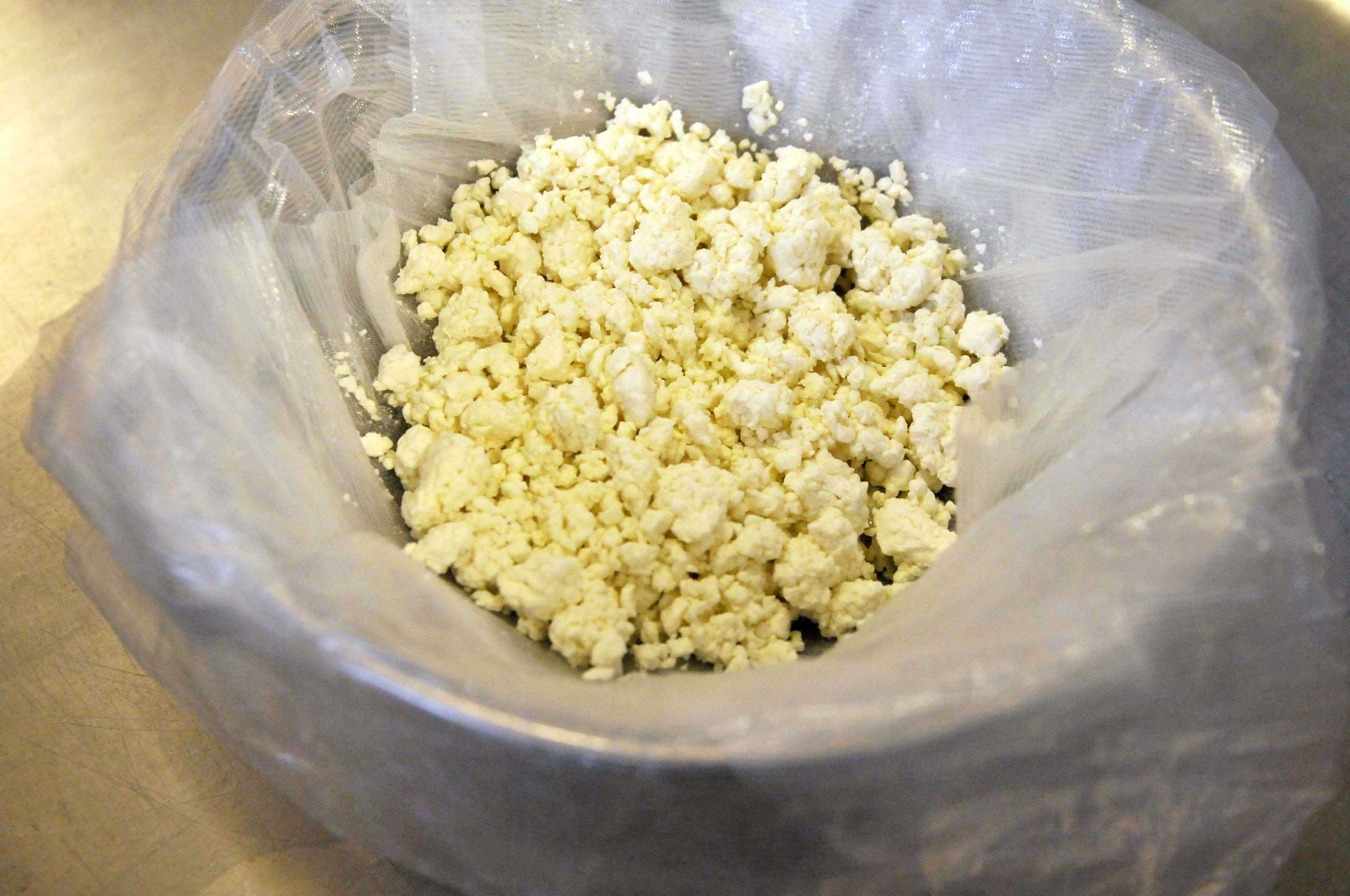

Dairy science Ph.D. student Keely O’Brien, who teaches the lab portion of the class, said the process of making cottage cheese began at 8 a.m. on Thursday by adding bacterial culture and rennet — cultured milk extracted from unweaned calves’ stomachs — to milk. The bacteria produces acid that combines with enzymes in the rennet to curdle milk into cheese.

By class time at 1:30 p.m., the mixture had formed curds. The students cut them into pieces and cooked them over low, slow heat to release whey that must be drained off.

O’Brien said people should appreciate fermentation, which is part of cheese-making, because it is the oldest method of food preservation. Basic fermenting skills have translated through generations, but processing methods have changed and science has progressed, she said.

“Our ancestors didn’t know why it was happening … but the students learn about that,” O’Brien said.

Mark Rule, animal science senior, said he likes learning the science behind common dairy products — and some that are less common, such as kefir, a fermented drink made with milk and grains of yeast and bacteria. It is important to know how foods are made so they can be made cheaper, using natural ingredients and in home and industrial settings, he said.

The best part of the class?

“We get to eat,” said animal science senior Mandy Montreuil.

Being able to whip up some yogurt at home when a craving strikes is special, Montreuil said, because she and other students know not only how to successfully follow a recipe, but how the bacteria in that recipe can either “kill you or provide awesome food.”

Class teaches science behind making dairy products

November 3, 2013

LSU animal science senior Katie Coleman (left) and animal science senior Mandy Montreuil (right) examine the process of making cottage cheese Thursday, Oct. 31, 2013, at the Dairy Science Building.