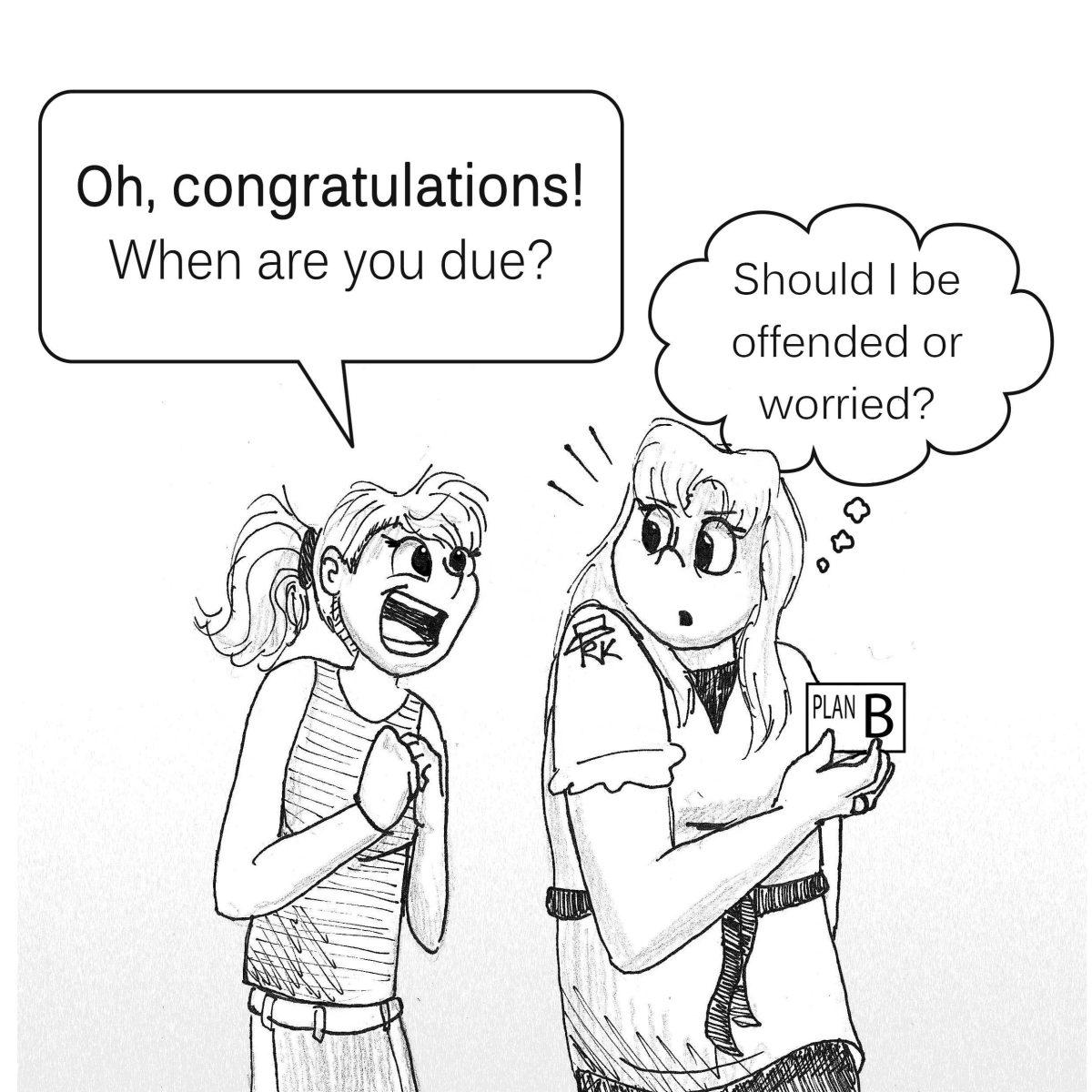

News broke Nov. 25 that Plan B contraceptive pills should really be plan C or D. Researchers found that the drug, commonly referred to as the morning-after pill, is less effective in women who weigh 165 pounds and almost ineffective for women weighing 175 pounds or more.

This means that the LSU freshman 15 poses even more of a threat to students than before.

With a product holding so much power over a woman’s life, you would think the manufacturers would want to inform the public of its limits. But I’m sure that would have cut profits too much, so why bother?

The findings about Plan B’s weight restrictions were accidental – they were discovered while conducting other tests on contraceptive options.

So, to be clear, that means that Teva Pharmaceuticals, the company that made Plan B, allowed its product to be sold before sufficiently testing it.

Teva refused to comment on its talks with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to any news publications.

There was rumor of retracting the drug until changes can be made to the labels indicating the weight restrictions, but retraction could mean uproar from a few college campuses adamant on keeping the pill handy.

A Pennsylvania college actually disperses Plan B through a vending machine, making it readily available for students who can’t make a trip to the store.

Although there is no data saying exactly how many college students use Plan B, it’s undeniable that the drug is prominent on college campuses. This slip-up has impacted women across the country that have taken the pill and still wound up pregnant.

More than one third of American adults were obese in 2009-10, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The average weight of women ages 20 and older is 166.2 pounds, which is above the limit of the Plan B findings.

These facts could lead to some complications; specifically, some complications that let out a cry about nine months later.

This leads me to be curious about what other products companies are selling before they conduct necessary tests. With something so weighty, you would think that the manufacturers would want to be certain of a success rate.

But it seems like companies focus more on their potential profit than the health risks of their product.

Studies on other basic drugs like Advil or Nyquil take years to conduct with various focus groups. Yet so many forms of birth control go on the shelf for women after minimal assessments. Only later, when health problems arise, are studies conducted that show malfunctions in the contraception.

Yaz, advertised as a new generation of birth control pill that would prevent pregnancy and help women lose weight, faced a potential recall shortly after its marketing peak when studies showed its chemical makeup had unhealthy side effects.

While this product is still on shelves, as many as 11,300 women filed lawsuits against Bayer because of Yaz.

If lawsuits weren’t already in the cards for Teva Pharmaceuticals, then I’m sure some will be dealt out in the near future.

Just because there is a demand for birth control does not mean a rushed product is the answer. There is no point where profit and speed should outdo the importance of a products health performance.

Wrongs will be righted, and the Plan B packaging will be altered to address the weight specificities. Yet the principal remains that, once again, women’s health products aren’t getting the attention they deserve.

Annette Sommers is an 18-year-old mass communication sophomore from Dublin, Calif.

Opinion: Plan B, morning-after contraceptive pills ineffective

December 2, 2013

Plan B