The word “microaggression” isn’t a thing yet, but it will be soon.

While sitting in one of my classes, I started talking to a group of people about our latest assignment.

We didn’t know each other, so they asked me what my name was and I politely replied and asked for theirs.

The conversation reached a halt at their realization that I have a Hispanic name.

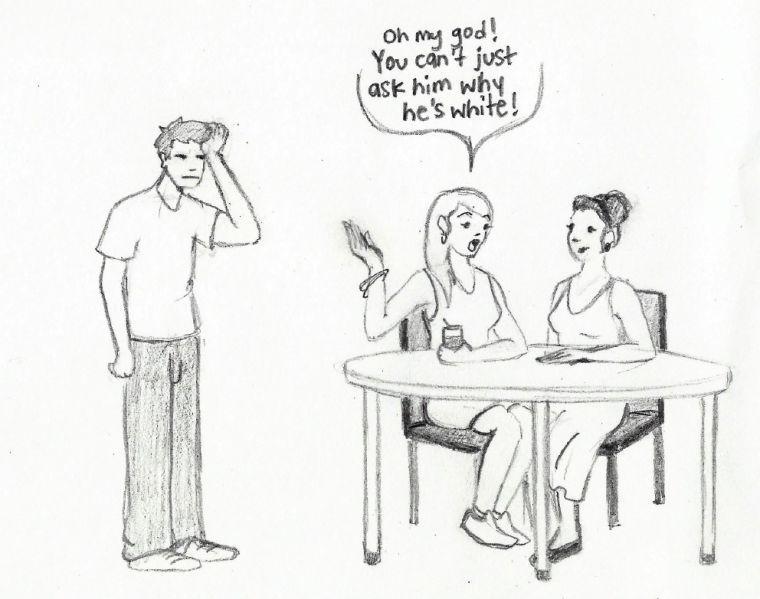

“Jose? Oh my God, you don’t look Hispanic at all!” or “Your English is so good. How did you do it?” are some of the comments I’m used to hearing in situations like this.

I moved to America almost five years ago, so you’d think I would be used to these statements of awe over my mastery of the English language or about the “non-Hispanic-like” color of my skin.

Truth is, I’m not.

The group was in no way being patronizing or racist toward me, but in a way, I did feel insulted because I don’t consider the fact that I don’t have a foreign- sounding accent or that I am a white-skinned Hispanic person to be a huge accomplishment.

I’m just not how preschool teachers portrayed Latinos in their word-teaching flashcards, and American brains can’t handle that.

This interaction is one of many examples I have of what social media now calls microaggressions.

A term first used only in academic settings by racial theorists and sociologists in the 1970s, the term has slowly become a phenomenon in the digital world after two Columbia University students founded The Microaggressions Project.

On the project’s website, people can post snippets of day-to-day instances where they felt insulted, belittled or unappreciated.

It’s like the Whisper app, but with legitimate reasons to complain about life.

Since the foundation of the project, universities across the U.S. have created their own microaggression pages on Facebook and other social media as an outlet for college students to shed light on the daily, subtle abuse they live with, and I believe the University’s student body would benefit from a page like that.

One of the things I like about the website is that its goal isn’t to criticize the ignorance of American society, because the vast majority of the experiences posted were not intentional incidents.

The goal of the website is to show how commentary, embedded in our minds by the society we are raised in, can have an abusive effect on our daily lives. Since everyone is used to brushing off this type of commentary — myself included — we ignore the fact that it is happening and, in consequence, we do nothing to change things.

When I moved to America and had my first experiences with microaggressions, my parents told me to get used to it because that’s just how society is — something they continue to tell me to this day whenever I complain about it — but I am glad these students from Columbia took initiative and are attempting to change the world, one post at a time.

Our society is damaged, and even with a contribution as small as a post on a website, we can change the way we view each other’s differences.

Last year, everyone was obsessed with LSU Confessions. Maybe now someone can start LSU Microaggressions, and it’ll become the new Facebook thing.That way, we can actually do some good when we’re not paying attention in class.

Jose Bastidas is a 20-year-old mass communication junior from The Woodlands, Texas.

Opinion: ‘Microaggressions’ are proof of a flawed society

March 26, 2014

More to Discover