Editor’s Note: This is the second column in a three-part series discussing racism in America.

Baton Rouge native Torrence Hatch, better known as local rapper Lil Boosie, was released Wednesday from the Louisiana State Penitentiary after serving time for drug charges. For years, we have heard the phrase “Free Boosie” as supporters have claimed his charges to be unjust.

I’d agree there is little justice in the war on drugs. The war on drugs has quickly turned into a war on marginalized communities.

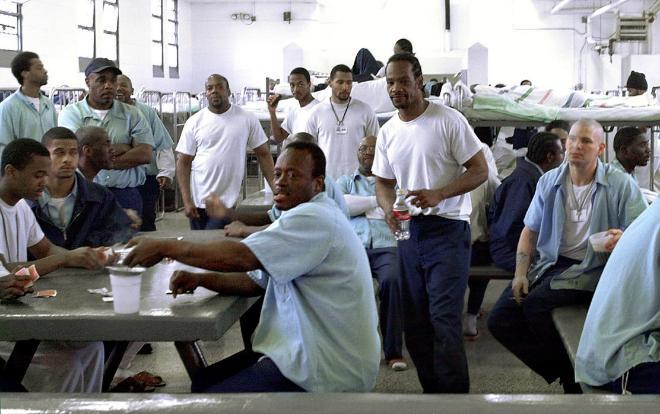

In August 2013, a Washington Post article reported the prison population in America has quadrupled since 1980, with the largest factor being longer sentences for drug offenders. The majority of those serving for drug offenses are racial minorities.

It’s possible the racial divide of the Americans serving for drug offenses is proportional to the racial divide of Americans who use drugs, but it’s unlikely when we look at the history of drug use in America.

In the 1980s, there was massive hysteria surrounding the use of cocaine. It was followed by disproportionate punishment between those who used crack-cocaine and those who used the purer cocaine.

Cocaine in powder form was used mostly by the upper class who could afford it, while smokeable crack-cocaine was found mostly in lower class, minority communities.

Bryan McCann, assistant professor in the Department of Communication Studies, had much to say about this, as he studies the racial divide of the criminal justice system.

“Crack had a very black face,” McCann said. “But there is a fine line between identifying the war on drugs as racist and claiming that it is an explicit conspiracy by powerful white men attempting to screw over black people.”

Conspiracy or not, the racial divide is evident in the recent movement for legalization of marijuana. The movement’s face is white. The arguments for medicinal purposes and safe recreation are voiced by white activists.

But the arrests and incarceration are against black and Hispanic people.

Laws such as prohibition of drugs and alcohol allow law enforcement to be selective. We know there are just as many white students on LSU’s campus using drugs, but we will see more black students getting possession charges.

Maurice Williams, general studies senior, said it’s no secret in the black community that there are laws that will put African-Americans in jail.

“You can’t just say that you happen to catch this group of people doing it,” Williams said. “You have to be looking for those people.”

And the consequences are real. Felons can’t vote, making it harder for those targeted marginalized communities to be heard. And the incarceration rates perpetuate the stigma surrounding black males as criminals.

Two weeks have passed since LSU student Leila Wolfe reported to police that she was the victim of an attempted abduction near Patrick F. Taylor Hall. While this crime is scandalous from the University’s perspective, nationally it is just another case of an imaginary black suspect.

In 1989, Charles Stuart caused a racially inflamed manhunt for the black male who he claimed had fatally shot his pregnant wife during a violent carjacking. His brother-in-law later confessed to police that Stuart was responsible for the murder.

In 1994, Susan Smith claimed a black man had carjacked her and kidnapped her children. It was later found that she had allowed her car to roll into a lake, drowning the children.

And just before the 2008 presidential elections, a campaign volunteer for Republican John McCain carved the letter “B” into her face and reported to police that she had been the victim of a politically charged assault by a black man.

Wolfe wasn’t the first, and she certainly won’t be the last to claim a vicious attack from a dangerous, scary black male. These allegations have perpetuated a stereotype that will be difficult to overcome.

Williams commented on this facet of racism, pointing out that Wolfe didn’t make a conscious decision to blame half of LSU’s campus, but her allegations hold more consequence for the black male population than they did for her.

This consequence is one that Williams’s parents foresaw and was consistent during his upbringing.

“People feel threatened by assertive black boys, so we’re taught not to be assertive because it could be misinterpreted as a threat,” Williams said.

There are parents who feel it’s necessary to raise their children to be passive because they fit a physical description commonly associated with crime, and it is more common than you may think. Those children can grow up to see their history and culture as a burden that makes them a target rather than something to be celebrated.

In an America with selective enforcement, drug laws are useless. They only serve to further discriminate against minorities and perpetuate the idea that some Americans are born criminals.

Jana King is a 19-year-old communication studies sophomore from Ponchatoula, La.

Opinion: Stereotypes make war on drugs harmful for minorities

By Jana King

March 6, 2014