Yesterday, October 28, would have been the day that Jonas Salk turned 100 years old. Salk, though now most famous as the subject of countless daytime PBS specials and pub trivia questions, was originally recognized for developing the polio vaccine that eventually eradicated the deadly disease from the Western world.

These days, it’s hard for us to realize the enormity of Salk’s contribution to humanity, both because we’ve largely forgotten how bad the polio epidemic was and because we have nothing to compare it to.

Now we freak out if we hear that one Ebola-ridden traveler has made it into the country, because we fear the kind of outbreak that’s been happening in West Africa could happen here. But before Salk’s and other vaccines became commonplace, there was a polio outbreak of about the same size in a major American city every year.

This year, about 5,000 people have died of the Ebola virus infection across West Africa. In the summer of 1916, more than 6,000 died of polio. In 1949, just three years before Salk finished his work on the vaccine, almost 3,000 died of polio, and thousands more were sickened or handicapped.

If you want to imagine the kind of impact Salk would have had today, consider this — if West Africa keeps seeing the same numbers of Ebola victims every year for about the next 50 years, and then someone comes along with a prevention measure that all but eliminates the disease, that person would be about on Salk’s level.

All that, and Salk refused to patent or make any kind of profit on his discovery.

But apart from being a main contributor to eliminating one dreadful disease from the planet (though polio has made a disturbing resurgence in Asia and East Africa in the past few years), Salk provided a model for preventing other dangerous viral infections and a thoughtful figure unafraid to question the medical status quo.

Most vaccines work by introducing a dead or deactivated sample of an infectious agent to a patient’s body, essentially allowing the body to practice its immune response on a harmless dummy. When Salk was getting his medical agent, this was common practice, but it was believed this process wouldn’t work for viral infections like polio.

Salk was unsatisfied with his teachers’ explanation, and his ensuing work using a “dead” virus resulted in a vaccine that, 10 years to the day after the death of polio’s most famous sufferer, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, proved to be safe and effective.

Salk’s selflessness and bravery saved the lives of thousands, so even though we’re a day late, take a day to remember a man who recent history largely has forgotten.

Gordon Brillon is a 21-year-old mass communication senior from Lincoln, Rhode Island. You can reach him on Twitter @tdr_gbrillon.

Opinion: Vaccine pioneer Salk shouldn’t be forgotten by history

October 28, 2014

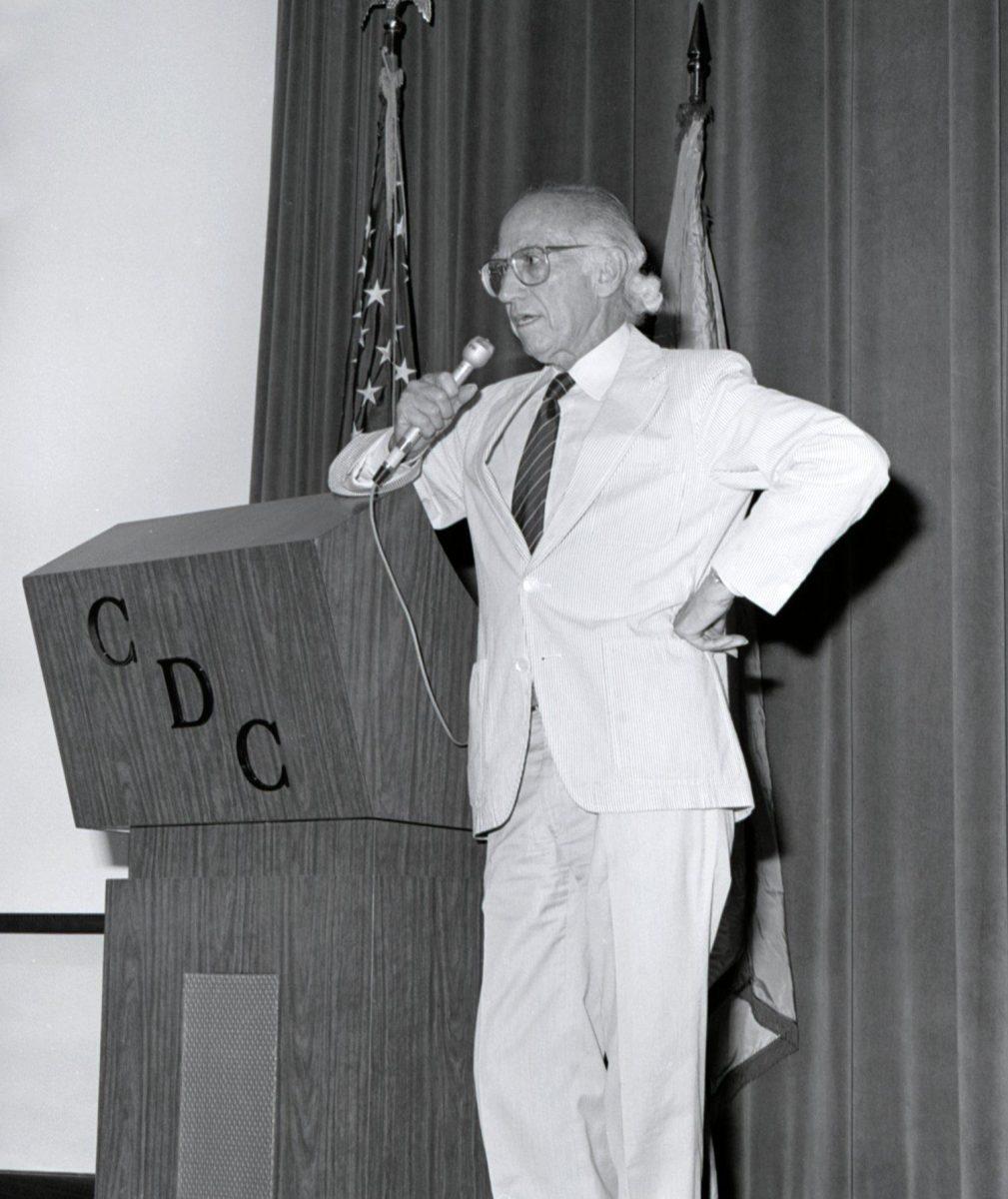

Jonas Salk, 1988

More to Discover