Art tells a story. May it be the story of a person, a group of people or a specific location, art recounts someone’s thoughts or emotions.

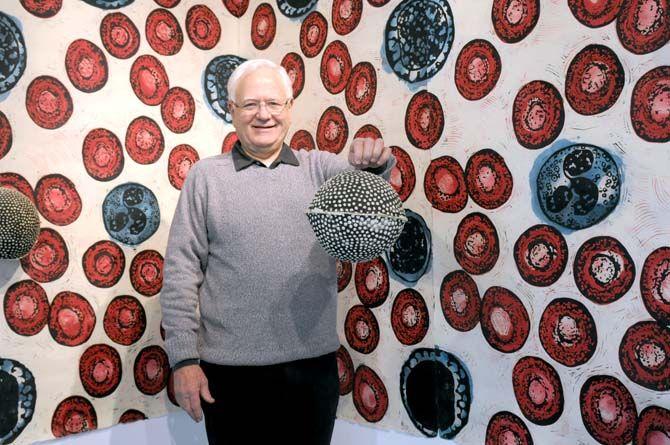

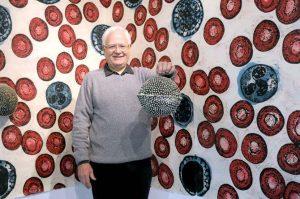

For HIV psychiatrist Eric Avery, art is an opportunity to tell the story of his experiences and his patients in his new Glassell Gallery exhibit “HIV and AIDS: Witness, Healer, Survivor.”

Avery began making art at a young age and found himself specifically interested in printmaking art. He decided to pursue a career as an artist at the University of Arizona. Unsure of what to do after graduation, Avery’s print teacher suggested he follow another one of his passions by going to medical school to become a doctor.

After being accepted to the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB) with an art degree, Avery went on to receive his M.D. in psychiatry. He moved to New York to practice psychology, still making art in his spare time. Despite living a life he’d always wanted, Avery found himself unsatisfied.

In the late ’70s, Avery volunteered with humanitarian aid organization World Vision to assist with Vietnamese refugees who were leaving Vietnam and moving to Indonesia. He worked on a ship for years with the Vietnamese refugees until World Vision asked him to travel to Somalia, where there was a drought and famine.

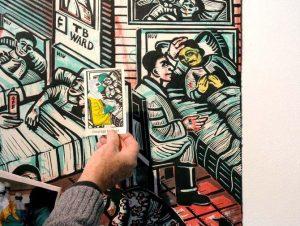

To combat the depression and harshness of the area, Avery began creating wood carvings, depicting what he saw during his travels.

“This was the first time I had truly made something that connected my life and what I’d seen around me,” Avery said.

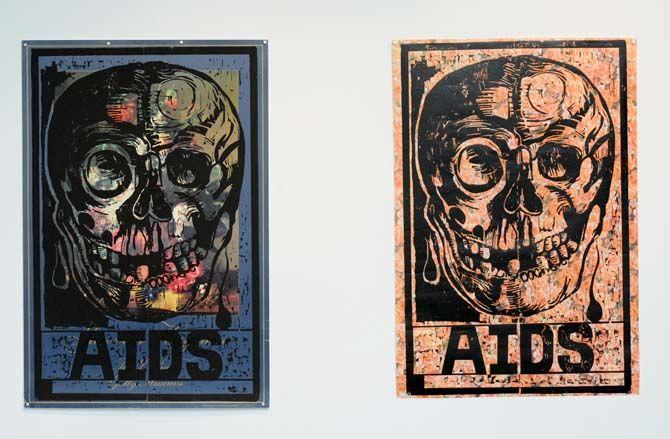

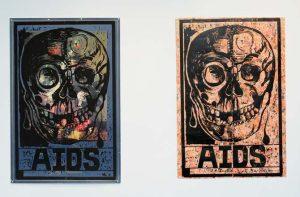

He returned to the United States a changed man. After seeing the struggles of living in a third-world country, Avery began creating darker art focusing on death and epidemics.

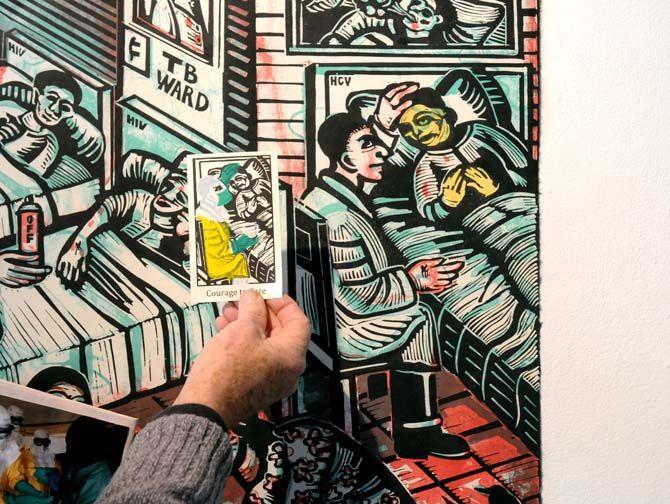

During his time in Texas, Avery’s friends began to die from AIDS. He returned to UTMB as the head psychiatrist of the HIV clinic. For 20 years, he continued to practice art and treat HIV patients.

Since his retirement from professional medicine, Avery has gathered a few of his works for an exhibit, which will be displayed at the Glassell Gallery.

“This exhibit is a chance for me to practice medicine in the aesthetic dimension,” Avery said. “Now that I’m fully in the art world, it’s time to develop a clinical practice within it.”

As a homosexual man, Avery said he empathized with many of the patients he encountered during his years at UTMB. He understands that HIV can change the way a person views the world around them and tries to encompass that in his artwork.

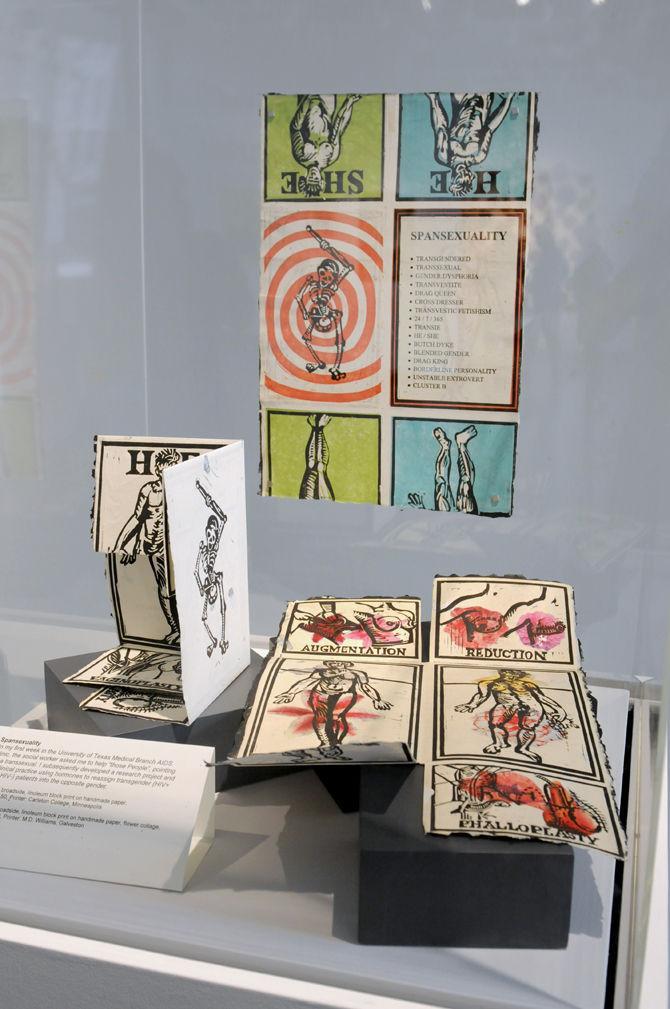

Topics like Avery’s first blood test and the process the HIV virus takes to infect a cell can be seen through his work. He has created wooden replicas of HIV cells with condoms inside as an installation piece. On one wall, Avery uses toilet paper to show the steps of using male and female condoms.

Along with screenprints and paintings, Avery created a small book about being tested for and noticing signs of depression. He said he hopes it can become a useful tool in clinics across America and not a “simple throw away brochure.”

While Avery wants patrons to appreciate the art for its beauty, he said what he wants more is for every person who enters the gallery to understand the gravity of safe sex and HIV’s affect on the world.

Avery said he believes through this gallery, more people will join the combined effort to finding a cure for HIV and AIDS.

“Doctors have told me before they would rather have HIV than have diabetes,” Avery said. “Nobody wants HIV, but by working together, we’re slowly finding ways to take it down.”

The exhibit’s name stems from Avery’s experiences in the medical field. He has witnessed countless deaths during his time practicing medicine. Avery has helped heal many, including himself, through his psychiatry and art. Most importantly, he has survived seeing more than what he believes any person should have to.

“The way I survived was by making art of what I’ve seen,” Avery said. “It has helped me sublimate and continue to live and grow.”

HIV psychologist creates art exhibit based on years in the field

October 27, 2014

Dr. Eric Avery’s exhibit HIV/AIDS: Witness, Healer, Survivor will be at LSU’s Glassel Gallery October 28 – December 7, 2014.