LSU’s Faculty Senate and Faculty Council have been violating Louisiana’s open meetings law since its implementation in 1973.

The Senate and Council are representative bodies for LSU faculty members. They’re also public bodies since they’re part of a public university, which makes them subject to the state’s open meetings law.

Since the establishment of the Faculty Senate in 1973, the same year the open meetings law was passed, Senate leadership has failed to properly record votes.

A deep dive in the Senate archives by The Reveille reveals that at no point in the Senate’s nearly 50-year history has the body properly recorded votes.

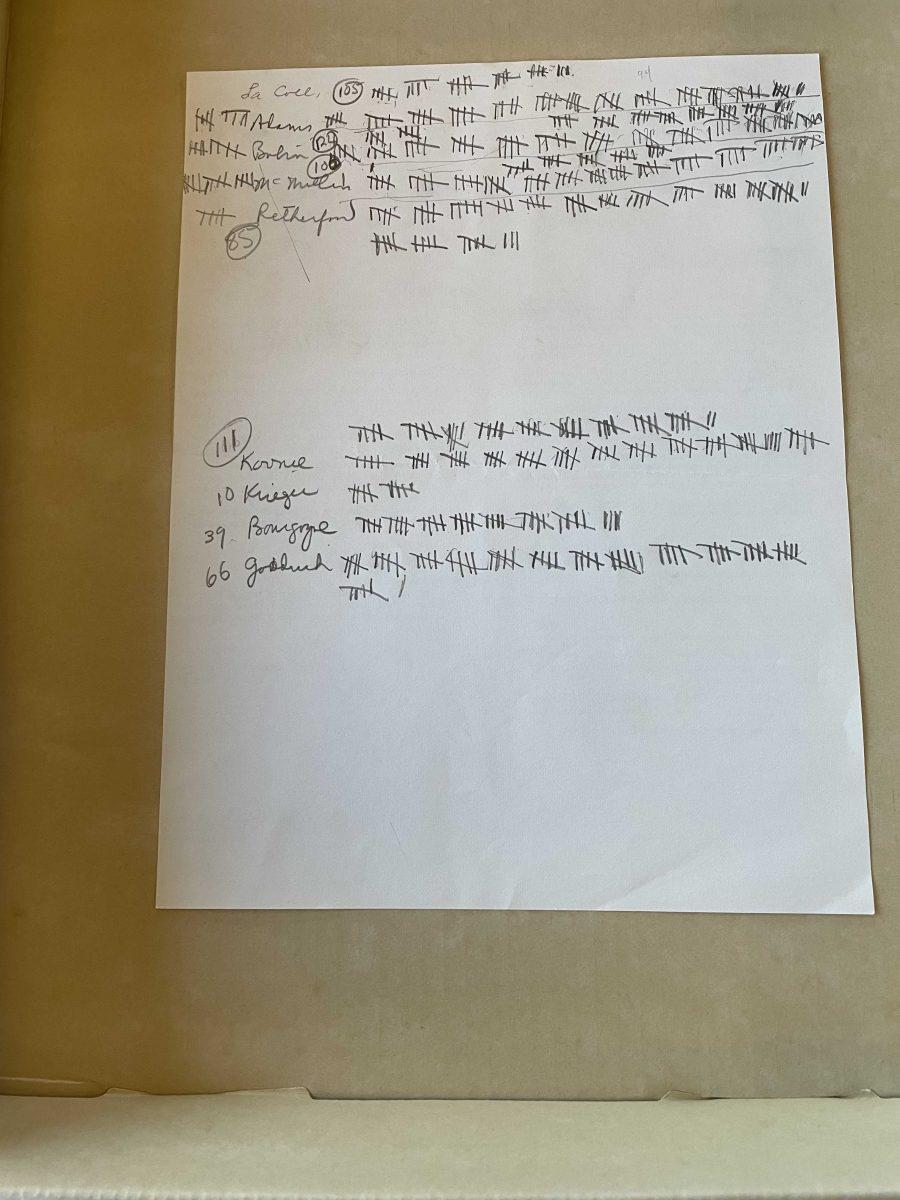

The closest thing to a recorded vote in either Faculty Senate or Faculty Council archives was a tally of votes from an April 1985 Faculty Council election. The tally does not include names, however, still ruling it out of compliance with open meetings law.

As reported at the February 2022 Faculty Senate meeting, it was discovered that the body does not know when they last passed a constitution. Constitutions aren’t required under open meetings law, but the lack of guidelines is posing a problem as elections approach.

The Faculty Council has been violating the law as well, but the council has never met consistently, especially compared to the senate. It’s unclear when the Council was established, but it certainly predates the open meetings law.

The Council is also much larger than the senate, as it contains all faculty members with rank of instructor or higher at LSU, which is over 1,000 people.

This leads Scott Sternberg, an attorney with expertise in open meetings law, to think that both bodies operated out of ignorance.

“They probably didn’t realize they’re reading a public body at the time,” Sternberg said. “LSU has been around longer than the open meetings law.”

The discovery comes a few months after the Faculty Senate’s illegal executive session, when the body booted members of the public out of a public meeting, including a Reveille reporter, without following proper protocol.

Daniel Tirone, a senator and political science professor, said he is understanding of violations that happened earlier in the body’s history, but is disappointed that the body has not made more of an effort to comply in more recent history.

“I have been told that around 2015 or 2016 it was determined that the Faculty Senate qualified as a public body under open meetings laws,” Tirone said. “I’m therefore more understanding of the open meetings laws violations that occurred during this period. What is more difficult to reconcile is why we did not comprehensively update the operations of the Senate and other related entities that qualify as public bodies following the determination that open meetings laws applied.”

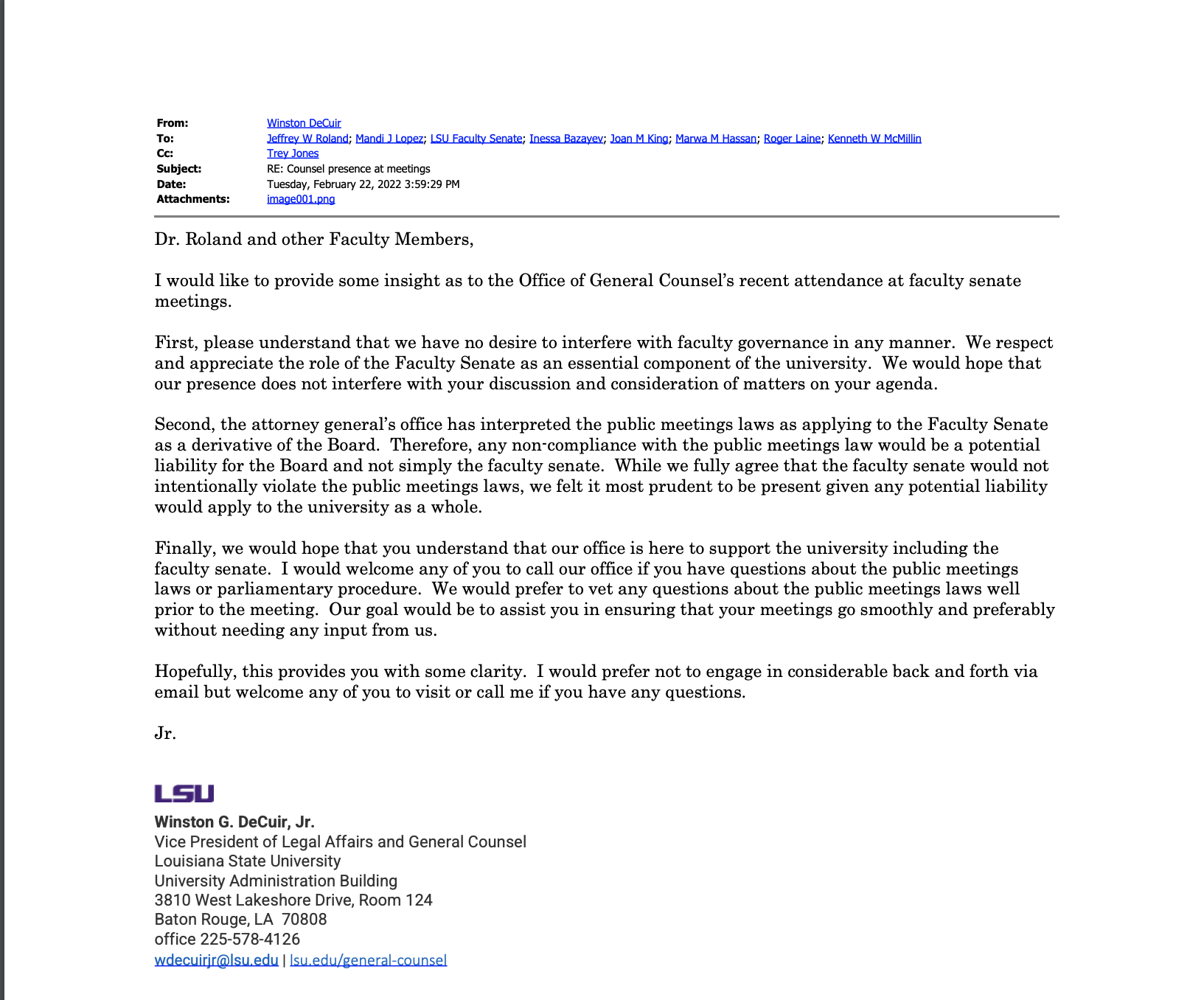

The extent to which LSU General Counsel has been guiding the Faculty Senate is unclear. The Reveille requested documentation of all communication between members of the General Counsel’s office and members of the Faculty Senate Executive Committee in which Faculty Senate business was discussed.

Out of the over 700 pages of email threads, only a small handful of pages include direct responses from either General Counsel Winston DeCuir or Deputy General Counsel Trey Jones.

One email, from DeCuir, discusses the reasons for a representative from the General Counsel’s office regularly attending Faculty Senate meetings.

“The attorney general’s office has interpreted the public meetings laws as applying to the Faculty Senate as a derivative of the Board. Therefore, any non-compliance with the public meetings law would be a potential liability for the Board and not simply the faculty senate,” DeCuir wrote in an email to FSEC members. “While we fully agree that the Faculty Senate would not intentionally violate the public meetings laws, we felt it most prudent to be present given any potential liability would apply to the university as a whole.”

Outside of this one email, the only other responses come to very specific questions about what open meetings law allows, such as whether zoom meetings were permissible or whether the FSEC is required to vote on the Faculty Senate agenda.

Despite DeCuir’s message that the Faculty Senate’s compliance, or lack thereof, with the law was a liability for the university as a whole, there is no evidence in the records that the office provided advice on how to correct the body’s multiple Open Meetings Law problems.

Faculty Senate President Mandi Lopez said in an interview that she has consulted with a variety of sources, including open meetings law experts, representatives from Attorney General Jeff Landry’s office and former Faculty Senate leaders, but did not provide any names.

“I’m not working with anyone specific. I looked at any source of information that I can find, including reading it myself,” Lopez said.

The Faculty Senate is making steps to untangle their Open Meetings Law problem.

The Faculty Senate is currently planning a May meeting of the Faculty Council, at which Lopez said they intend to ratify the Faculty Senate constitution approved by the Senate in 2020.

Lopez acknowledged that the outcome is uncertain, as the Faculty Council has struggled with meeting the quorum required to conduct business. Lopez said she is doing “everything [she] can” to ensure the May meeting complies with open meetings law.

How the body acts in the interim remains to be seen. The Senate is slated to hold an election of officers in April, but has held internal debate as to which constitution will be used.

At the February Faculty Senate meeting, President Mandi Lopez announced that it was possible that the most recently passed legal constitution was the original 1973 version. At the Faculty Senate Executive Committee meeting Wednesday, Lopez announced that after conferring with various legal experts, it was determined that the 2005 constitution would be used.

Records relating to the passage of the 1973 constitution could not be found in Faculty Senate archives, which raises a problem even if it was passed. The same problem exists for the 2005 constitution, which has the additional problem of it being passed by mail vote.

Lopez said at the meeting that the experts advised her to use the 2005 constitution, despite the issues, as the deadline for raising open meetings law complaints was passed long ago. The law provides for complaints up to 60 days after the violation occurred.

Sternberg said he “didn’t envy” the situation, which he dubbed a “cluster,” leaving off the expletive usually accompanying the term.

“There’s what’s legal and there’s what’s practical, and in this case, you know, it sounds to me like they probably should just do a new constitution vote on in a meeting and be done with it,” Sternberg said.

The Senate has also been making steps toward compliant record-keeping. The minutes from the Jan. 25 meeting, which is the most recent meeting with publicly available minutes, include more inclusive records of votes taken, although not full compliance. One vote includes the names of those who voted against a motion, but not those who voted for it.

On Thursday, the body will undergo open meetings law training provided by the Louisiana Attorney General’s office. The training is part of an agreement the university came to in response to a complaint made with the AG’s office regarding the November violation of open meetings law.

While the training seems to be a step in the right direction for the body, it is unlikely that it will include advice to the level that is needed to bring the Faculty Senate back into compliance with open meetings law.