Four LSU students developed an AI tool last fall that could enable hospitals to automate cancer staging.

“Our project was to develop a large language model that can take cancer pathology reports, specifically breast cancer, and give them to LLMs that both tell the staging of the cancer and help patients to better understand the reports themselves,” said junior Yueh Wang.

Wang is one of four computer science majors, including senior Kyle McCleary, junior Aditya Srivastava and sophomore Jamar Whitfield, who developed the tool last fall in an honors course at the university.

The project’s sponsor was professor Lucio Miele, chair for the Department of Genetics at LSU Health New Orleans’ School of Medicine. Miele’s work has been featured in biomedical journals, and he serves on multiple grant review panels and foreign research funding agencies.

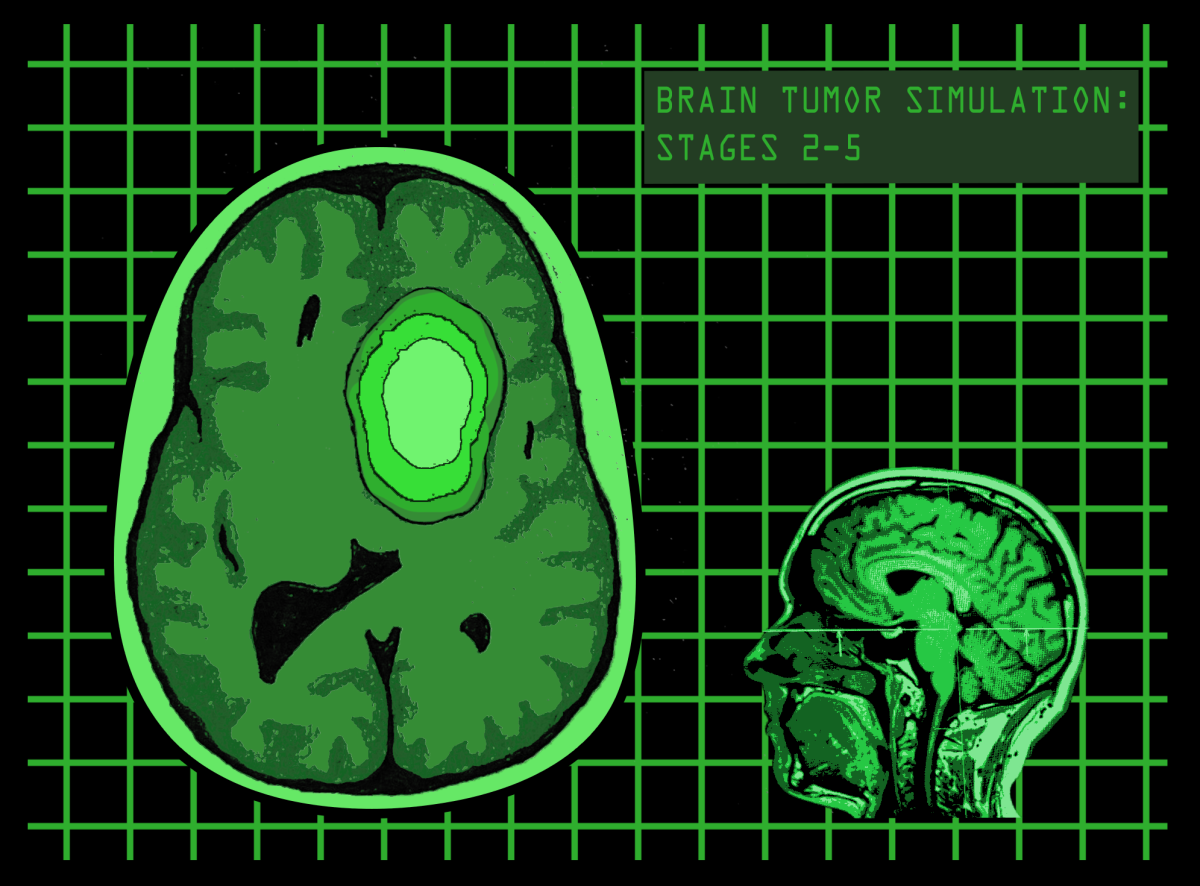

Staging is the process by which doctors determine a cancer’s severity by determining its size and spread. There are a handful of staging protocols. The most common is the TNM system, which looks at the size of the tumor, the condition of nearby lymph nodes and the degree a cancer has metastasized, or spread through the body.

The five stages of cancer, zero through four, provide a general description of specific staging protocols like TNM.

The LSU students’ staging tool used optical character recognition to scan doctors’ notes then determine stage with the TNM system based on the information.

Staging can be a long and time-consuming process for medical professionals because it involves collecting and synthesizing many documents.

“They collect thousands of reports. They have a very large number of files they have to go over, like pathology reports. Our involvement in it will improve their efficiency and save time,” Wang said.

After the staging process, medical staff can export the information to JSON, CSB or Excel files to make them more compatible with their own systems.

Baseline tests during last semester reached 90% to 92% effectiveness. Among measures to ensure accuracy is a multi-pass process that assesses each stage and cross-references its findings to ensure accuracy. Cross-referencing uses what’s called the swiss cheese model, which involves compounding accuracy, bringing error down near zero.

“We’re going to thoroughly verify the accuracy of the pipeline is at least 98% to 99%,” McCleary said.

In cases where there is an uncertainty or unknown, the tool is trained to report inconclusiveness to avoid confident falsehood, what computer scientists call hallucinations.

All personal info is redacted prior to usage by the tool, so no sensitive info is used or at risk.

“Security in medicine is more important than almost any other industry, so being able to properly ensure we can deploy this stuff at scale without putting anything in danger is very important,” McCleary said.

The group also developed a framework and web app for deploying LLMs and other AI tools, named QueryLake. The model has a similar interface to ChatGPT but implements new features on top of existing language models.

QueryLake can be used to search uploaded documents from textbooks to pathology reports. Responses to queries have relevance scores for sourcing and show where the information was found for verification purposes.

Like the staging tool, QueryLake prioritizes security.

“We’ve been developing a very generalized framework that can be used for all types of stuff,” McCleary said. “I’ve built it with a database that’s properly secured. If they host documents on it, they’re all encrypted.”

More specialized pipelines, like the staging tool, can use permission locks to block access to protect patient information.

Unique to the QueryLake model is the option to make collections of documents, something McCleary compared to playlists. This would allow users to switch between collections with ease.

These collections could be shared, which offers countless applications, including use by instructors.

McClearly said he sees QueryLake as the perfect tool for instructors who want to push productivity as much as possible, especially technical courses like programming.

Common to the rise of AI is the anxiety that more able computers will mean less work for people, but McCleary sees it differently. For him, the two aren’t mutually exclusive.

“Pessimists will say we’re automating jobs away, but I think every meaningful job can save time not doing the menial stuff,” McCleary said. “We get to recycle our own time by using it on something more valuable.”