A survey conducted by a group of LSU capstone students this spring revealed rates of drug use were much higher among the LSU student body than previously thought.

The capstone group also discovered access to the life-saving opioid overdose drug, Narcan, lacking on LSU’s campus.

The survey—created for a political communications class by seniors Gabby Jensen, Ryley Young, Rachel Wong, Cameron Lavespere and Austin Bordelon—found 70% of respondents knew another student who used Adderall or Vyvanse without a prescription, with 57% of those respondents saying they knew someone who used the drugs frequently or very frequently.

Sixty two percent of respondents knew another student who used cocaine, with 46% of those respondents saying they knew someone who used it frequently or very frequently.

READ MORE: Most Title IX cases reported to LSU go nowhere

And 86% of respondents knew another student who used marijuana, with 75% of those respondents saying they knew another student who used it frequently or very frequently.

The capstone group found students wanted access to Narcan, but couldn’t find it on campus: 82% of survey respondents were interested in being trained to administer Narcan, but 96% of students had never seen it anywhere on campus.

The survey reached nearly 1,000 students from all grade levels and most of LSU’s colleges.

Three of the capstone researchers, seniors Jensen, Young and Wong, spoke with the Reveille about their group’s survey—and the university’s reaction.

How it started

Young said the capstone project was born from the group’s personal experiences.

“I think we hear a lot about the fentanyl crisis, we see drug use in our, you know, interpersonal relationships and lives,” Young said. “And it felt like a place that maybe we could recognize LSU had the potential to do more, and then also should probably be doing more.”

The group began by diving into the data.

In correspondence with the East Baton Rouge District Attorney’s Office, they learned the state of Louisiana had much higher overdose death rates than the national average.

In 2023, the national overdose death rate was just above 30 per 100,000 people, according to data from the D.A., Louisiana’s fatal OD rate in 2023 was just under 50 per 100,000, and East Baton Rouge Parish saw OD deaths at about 65 per 100,000.

In a hard-hit parish, in a state with increased rates, in a country experiencing an opioid epidemic—the capstone students wondered how LSU’s drug policy stacked up against other universities.

“The more we looked into it,” Jensen said, “the more we realized that LSU really was lacking.”

In their research, they found other schools dealt with the problem by providing information on and access to Narcan. But in LSU’s online presence, the only mention of the life-saving treatment came from a short release by the LSU Police Department and the university code, prohibiting drug use on campus, Wong explained.

READ MORE: Street Squad presents caffeine management tips

Narcan is available on LSU’s campus from three main sources: the Student Health Center, the LSU Police Department and in the university’s dorms.

Typically, resident advisers on LSU’s campus are trained on how to use Narcan in the event of an emergency. But when the capstone students visited dorms, they found some R.A.’s weren’t familiar with the drug; others had been trained, but didn’t know where to find their dorm’s supply of Narcan.

“It shows there’s a lack of information around what the action plan would even be,” Jensen said.

LSU has an action plan for fires, Jensen reasoned, and an action plan for when someone has a heart attack, where to find an automated external defibrillator, or AED. But LSU’s action plan for overdoses just wasn’t there.

“This was not something that the university is necessarily prepared for,” Jensen said.

Why were other schools putting so much effort into increasing Narcan accessibility, when data showed that Louisiana, and Baton Rouge specifically, had much higher overdose rates?

“One could argue that it’s out of care for their students” that other colleges are making Narcan more accessible, Jensen said, then paused to clarify: ”Not that LSU doesn’t care, but that maybe they need to take more steps.”

The group couldn’t make sense of the high drug use but limited access to Narcan they saw in the LSU community.

“We knew it was affecting our campus,” Wong said, knitting her brow, “and we wanted to take that to the next level and try to fix it.”

Making the survey

LSU’s Institutional Review Board is the organizing authority on campus that makes sure research involving human subjects complies with federal requirements. Anyone who wants to conduct a study that involves people is required to get approval from the IRB before starting.

Wong had already taken a certification course through the IRB for past projects. She recertified, then helped the capstone group submit its survey to the IRB for approval.

The student group worked with the IRB to address areas of improvement in the survey. Then, in late February, the capstone group got its go-ahead with a letter from the IRB approving the study.

The student researchers said they tried to construct their survey to encourage responses that were as truthful as possible.

“People might be nervous to admit to using drugs, even if we’re saying it’s an anonymous survey,” Jensen added.

So the capstone researchers formed questions they thought would compel more candid answers. Their survey asked respondents if they knew other students who used drugs rather than if they themselves used, hoping it would quell fear of potential legal repercussions.

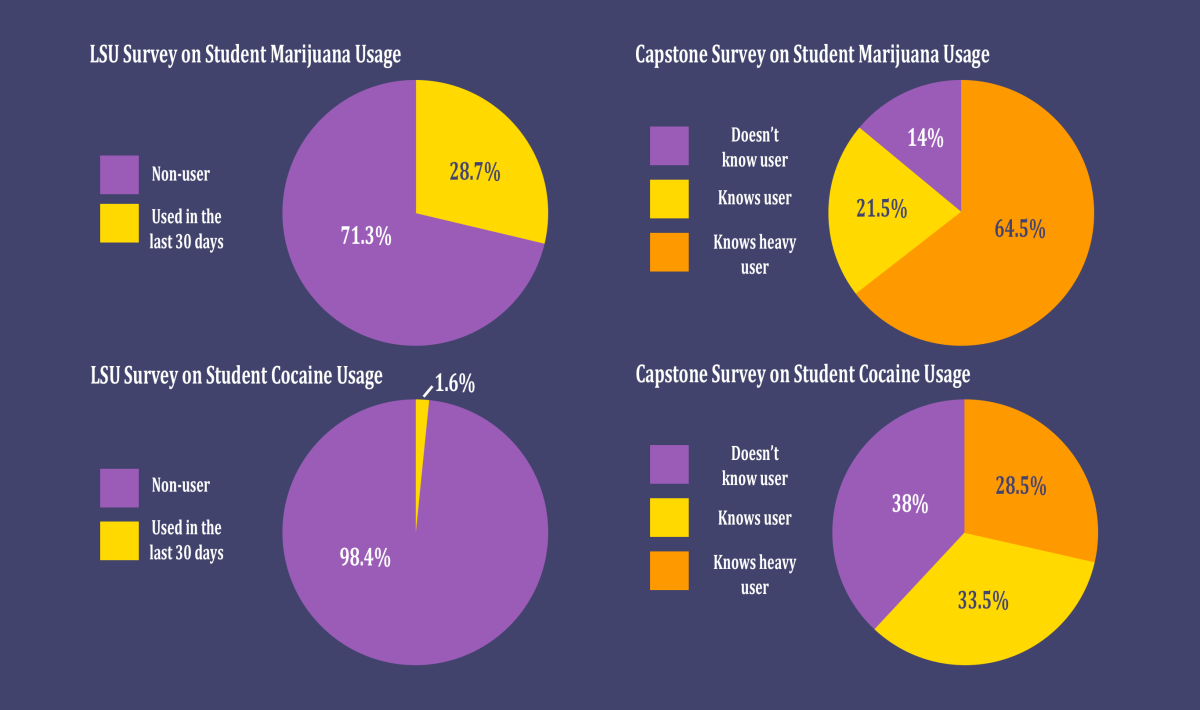

In a 2023 survey conducted by LSU administration, 28.7% of students said they had used marijuana in the last 30 days, and only 1.6% said they had used cocaine in the last 30 days. But the capstone group participants said they believe the questions in that survey may have discouraged students from answering candidly by asking them directly if they used drugs.

“I think that if you ask 100 college students if there’s a drug problem on this campus, you’re probably gonna get answers that side a little bit more with what our board says, rather than theirs,” Young said.

The capstone group also tried to position their survey to be as representative as possible, Jensen said: The survey’s respondents are spread evenly across academic year and college.

“And it wasn’t by convenience,” Wong said. “We had to email professors. We had to reach out to Greek chapters to try to visit. And we made efforts to make sure that it was a representative population.”

READ MORE: LSU legend Seimone Augustus to join women’s basketball as an assistant coach

The students corresponded with Manship School Dean Kim Bissell to get contacts for every student in LSU’s college of mass communication.

They also coordinated with LSU’s Student Health Center, from learning about Narcan access on campus to consulting the center’s drug use task force on how to construct their study.

“The Health Center praised our survey, they encouraged us to go out and collect information, and then they also greenlit our questions before we asked them,” Young said.

Then, when the students presented their findings back to Health Center representatives, they heard positive feedback.

“They did an amazing job,” the Director of Wellness and Health Promotion Michael Eberhard said in an email to the capstone group and officials from the Health Center.

In another salutary email, Assistant Vice President for Student Health & Wellbeing Dan Bureau called the survey a “need.”

Jensen said representatives from the Health Center told the capstone group they had a feeling there was a problem on campus, but without concrete data, it was hard to begin addressing that problem.

The student researchers hoped their survey could be that concrete data.

Making a difference

As the group learned more about the prevalence of drug use and the lack of Narcan access on campus, Young said he began to think of their project as a tool for, hopefully, shifting the LSU perspective.

“Narcan isn’t simply an emergency response that a police officer should give or a nurse in the Student Health Center,” Young said. “It can be a preventative one that you can easily equip students with if you have the ability to.”

Young and his team partnered with the Student Health Center to hand out free Narcan on LSU’s Free Speech Alley on two occasions this spring. They were able to get funding through a pre-existing grant from the LSU Board of Supervisors.

The free Narcan didn’t last long. On both occasions, the capstone researchers found students were eager to take advantage of the access, and within a few short hours all their Narcan had been given away.

To Jensen, Young and Wong, their survey felt like proof of what they already knew: that more LSU students were using drugs than it seemed. That more LSU students wanted access to Narcan.

Through their school project, the capstone students had become accidental experts—and intensely passionate about the emergence of student drug use.

“Our mission at the end of the day was just to help these students,” Wong said.

In the media and LSU’s response

The capstone researchers first shared their findings with news outlets in early April. WBRZ reporter Nicole Marino wrote an article explaining the survey and the students’ mission to increase Narcan access on campus. Marino is also an LSU journalism student and reporter for the student-run TigerTV.

In the following days, WBRZ received emails from LSU’s Vice President of Marketing and Communications, Todd Woodward. One email arrived with the headline: “Poor Journalism.”

Woodward wrote that LSU did not have a drug problem, adding that there was no correlation between the non-opioid drugs included in the survey questions and Narcan, the opioid overdose drug.

Upon learning of the emails, the capstone students pointed to the fact that many people don’t intend to ingest the opioids lacing other drugs.

“All data points to the fact that most overdose deaths are happening because of accidental overdose, because people do not know that it’s in their drugs,” Jensen said.

In his emails to WBRZ, Woodward wrote that the story bordered on defamation and that the student survey was “faulty data.”

“I’ll check in with our lawyers next,” he concluded.

Shortly after, WBRZ published another article detailing the interaction.

The student researchers’ professor, Bob Mann, voiced his support in response.

“They [the capstone group] love this place and they are concerned about the well-being of students in a way that I’m afraid some administrators aren’t,” WBRZ quoted Mann, “so I’m really proud of them for speaking truth to power.”

Young told the Reveille he was shocked by Woodward’s emails, especially because the university had made no efforts to reach out to the capstone group to learn more about how the survey was conducted.

“You can say that there’s not a problem,” Young said intently. “But no one’s watching to see what’s going on.”

The Reveille interviewed Woodward over the phone in the weeks following his email exchange with WBRZ. His attitude toward the survey had shifted markedly, though he still took exception to both the student research and WBRZ article.

Woodward said he thought Marino’s story ought to have included LSU’s own drug-use figures for comparison against the new data.

READ MORE: LSU baseball’s season ends with staggering 4-3 extra-inning loss to North Carolina

He also took issue with the survey’s methodology, saying he thought it may have skewed the results. Instead of asking respondents if they used a particular drug, the new survey asked respondents if they knew another student who did. Woodward argued that just because 1,000 respondents know, for example, someone who smokes cigarettes, doesn’t mean that there are 1,000 people in a sample that light up. There could be overlap, he said.

But above all, Woodward said that LSU’s policy decisions weren’t up to him.

“I’m the marketing guy,” he said.

“Regardless of the source,” he had mentioned earlier, “it’s my job to protect the brand of LSU, to say, I think you’re looking at bad data,” he said, referencing the disparity between LSU’s own conclusions and the student survey’s findings.

On a somewhat conciliatory note, he said that if the student researchers wanted to see change on campus—an awareness campaign on the dangers of illicit drugs, or a conversation about increased access to Narcan—then he thought the LSU administration would be open to that.

Woodward also conceded that, despite his misgivings with most of the student data, he agreed the capstone researchers had proven LSU students want greater access to Narcan.

A meeting with LSU’s higher-ups

In the final weeks of LSU’s Spring 2024 semester, members of the capstone project met with LSU’s Vice President of Health Affairs Courtney Phillips and Vice President of Student Affairs Brandon Common. Hot on the heels of the WBRZ-Woodward kerfuffle, the student researchers discussed their hopes for how the university could change its Narcan policy.

“I think it was a pretty productive meeting,” Jensen said.

The student researchers explained to the two VP’s how their capstone assignment had evolved into a passion project—and their dismay when they learned that another student journalist, Marino, had received backlash for her reporting.

Despite the university’s initial response, Jensen said that in the meeting with Phillips and Common, she felt the two VP’s were receptive to the survey and willing to do something about improving Narcan access on LSU’s campus.

For next steps, Jensen said the capstone students had suggested stocking Narcan next to campus AED’s, or at the very least having one dose, in a high-visibility area, in each building.

For her part, Jensen said she’d be checking in to make sure that LSU moves forward on improving their policy. Jensen also said two of her fellow group mates, Cameron Lavespere and Rachel Wong would be at LSU’s law school next year and that they’d also be continuing talks with the administration.

“We’re going to make sure that this is happening,” Jensen said.

Oliver Butcher, Madison Maronge and Connor Reinwald contributed reporting to this article.