Stars still shone in the sky and the sun remained deep behind the horizon as hundreds of students gathered Monday morning to honor the memory of September 11th.

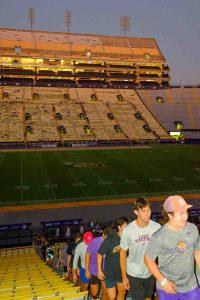

The air was cold. Crickets called. The city slept. Meanwhile students shook sleep from their limbs, filing into Tiger Stadium, readying themselves for the 9/11 memorial stair climb. The event, created by the LSU Corps of Cadets as a way to honor the tragic anniversary, has become a tradition since its inception last year.

“It’s important for us to do things like this—” said civil engineering senior Samuel Daigle, who serves as Logistics Officer for the Corps of Cadets. His voice cracked and rasped, a side effect of the yelling frequently involved in another of his leadership positions as Deputy Director of Operations for the LSU Air Force ROTC.

“To have this day, this moment, means a lot,” Daigle said, contemplating the rows of bleachers encircling the stadium.

In anticipation of the climb, many talked excitedly, tied and retied their tennis shoes, fidgeted with shirt-sleeves and skirt-lengths. A few looked skyward. Others grew silent in contemplation.

*

Few dates give us pause as 9/11 does. Few days compel the same quality and degree of reflection.

On the attacks’ one year anniversary, Reveille columnist Jason Martin spoke volumes with a short phrase at the end of one, terse graph.

“A sense of fear still lingers—” he wrote, “—like a bad dream that’s long past.”

On that day 21 years ago, Martin wondered how our dedication to the memory of 9/11 would change over time.

“Today The Reveille and other newspapers around the country will have special pages dedicated to remembering this date. But what about next year? Will the headlines be similar on Sept. 11, 2021, to what they are today?”

Opposite Martin’s 2002 column, a collection of quotes detailed students’ memories from the day the New York skyline folded in.

“I was in my media writing class and the professor came in and told us about the attacks,” said Chloe Wiley, who was then a sophomore studying mass communication, “I thought he was giving us another practice topic to write as an exercise.”

Of course, it wasn’t an exercise.

“I was confused and scared,” Wiley said, “I had the urge to go home and be with my family.”

Then-sophomore Patrick Trito was at work gathering materials from a warehouse when he heard the news on the radio.

“I can still remember all the faces, the shock and sadness and anger that everyone was feeling,” Trito said. “I remember the videos of the building being struck by the plane and it falling.”

Today, time has tempered the anger and fear. What was a raw cut now lies on the skin as a welt, a reminder of the old pain, still tender to the touch but perhaps healed.

Twenty-two years have passed since the attacks on the World Trade Center, Pentagon and the wreckage of Flight 93 opened a wound on U.S. soil, leaving thousands dead, thousands more bereft and the nation scarred.

Twenty-two years later, we continue to remember, but today, most LSU students are too young to have memories of their own. For them, 9/11 exists as a collection of others’ stories: those told by parents, friends and family; videos of black smoke pouring from the twin towers; photos of people falling from top floors and firefighters sifting through the deep, twisted rubble of the collapse.

*

At Monday’s stair climb, Commandant of the Corps of Cadets Lee Kostellic wore a buzz cut and a gray shirt. One of the few in attendance old enough to remember 9/11, he thought of his responsibility to pass on his knowledge.

It’s a “passing of the torch,” he said.

At the climb, students traced zig zags in the night up and down the bleachers above the visiting bench, then back to the beginning and again and again for eight laps.

Shirts drenched with sweat, hair stuck to foreheads in strands, heavy breathes punctuated the silence and the morning persisted in darkness.

But as the climbers warmed so, too, did their voices. Soon the empty stadium filled with calls, teasing, shouts, the patter of footfalls on the decline and thumping of soles on the incline.

“What y’all doing falling behind?” a student beamed, pumping her arms. “There’s a passing lane. Get there.”

A few who’d stopped to catch their breath in the cool air smiled back, jerking up to fall in line.

From the far side, a cadet began to sing.

“Tell me why.”

The crowd sang back, “Ain’t nothin’ but a heartache.”

“Tell me why.”

“Ain’t nothin’ but a mistake.”

Then, between the stadium and the sky, the sun began to rise.

The fast lapped the slow. The thoughtful stopped to check on the struggling. A few bounded. Many plodded.

Five, six, seven, eight—in passing, climbers exchanged which lap they were on.

“Y’all on eight?” asked Kostellic, sweating.

“No, nine.”

“Y’all doing extra? After my own heart. Cause mine’s gonna blow up.”

Then he turned to the crowd.

“Let’s go! Go quick!” he shouted, “They did.”

In small groups, over the course of 20 odd minutes, the climbers finished, popping bottles of water and gathering to sweat and pant in the rows above the north box. When everyone was done, the crowd packed tightly together for a photo. Arms swung around shoulders. Grins spread across faces. The sun shone brightly on their bodies, and few shadows cast in the glow.

More than twenty years after Sept. 11, 2001, the day of great anger, fear, confusion and loss has become a day of memorial. Those who gather, gather to remember the dead but also to embrace the living. To embrace life.

Between shutter clicks, the cadets in the front filled their lungs and began, again, to sing.

“First to fight for the right, / And to build the nation’s might,” they swayed, “Proud of all we have done, / Fighting ‘til the battle’s won, / And the Army goes rolling along.”