On Monday, LSU’s fall semester began. Classrooms whirred. Students walked. Professors talked. Then on Tuesday, it suddenly stopped.

Shortly after 7 a.m., downed Entergy transmission lines on East Parker Boulevard caused a campus-wide power outage, said Tammy Millican, LSU’s executive director of facility and property oversight.

Streetlights died. Intersections became four-way stops. The few cars humming around campus lurched and zoomed as drivers waved to each other, making hand signals from behind their windshields. While they rushed, however, the university stood still.

Just before 8 a.m., LSU students, faculty and staff received an alert indicating that the outage would close campus until 10:30 a.m. Shortly thereafter, another message arrived: “LSU will close for the day.”

In the absence of power, cicadas replaced the din of A.C. compressors. Gangs of squirrels staggered through the empty quad, apparently dazed by the heat. One climbed up and down the same column over and over searching for something but not finding it. Another lay in the shade on his belly with all four legs stretched wide. No one was there to bother him or force him up a tree.

Unknowing students wandered aimlessly or rushed from building to building—searching for an open door, someplace to eat, a sign of life—but found most doors locked and most food-spots closed.

Just after 10:30 a.m., wildlife ecology senior Josh Riddlebarger strode loosely toward the library’s south doors and gave them a tug. The glass rattled, but the bolt remained latched. A handwritten sign declared the spot, “Closed until 8/23/23”.

“Can you believe this?” he smiled, looking around, “I’m not quite sure how I feel, to be honest.”

Part of him relished the day’s unexpected turn; part of him did not. “My class was scheduled for 7:30,” said Riddlebarger, sitting down. “The professor went over some stuff and then he was like, ‘Oh, alright, guess you guys can head home.’”

A wisp of black hair slicked across his forehead in the heat. Sweat pooled beneath his eyes.

Cocking his head toward the empty campus, Riddlebarger said he was going home, “where I have A.C.” he laughed, then raised his hands in a gesture of futility.

Not far away, music therapy sophomore Mario Knox found the Student Union similarly shut, with the exception of a note.

“I just woke up from a nap,” he said, bleary-eyed. Another student tried the Union door and frowned.

“Closed?” she called out.

“Yeah,” said Knox, “Sucks, right?”

A few minutes passed as half a dozen people walked up the steps in succession, each learning suddenly that the Union was closed—many having seen their peers’ failure to enter yet compelled by the need to see for themselves. Down the street, Barnes and Noble was also locked for the day, and many students pulled unsuccessfully on its doors, but The 459 Commons and The 5 Dining Hall opened from 11:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m., serving boxed lunches, followed by dinner at 4 p.m.

Just before 10:30 a.m., however, power returned to campus. Streetlights resumed. Traffic picked up. Students remerged.

The familiar droning of little-known, underground machines and rattling mechanisms rose from grates in the sidewalks. Fluorescent lights buzzed. Loud clicks sounded from behind metal doors on the backsides of buildings, and in the parking lot between the Howe-Russell Geoscience Complex and Nicholson Hall, A.C. compressors fired with the enthusiasm and volume of small jet engines.

Amid record breaking temperatures and a heat-induced state of emergency, the outage left some 4,500 Baton Rouge residents without power, according to figures from Entergy.

LSU’s Tuesday disruption, however, is only the most recent in a series of frequent power outages, which have drawn heat from the residents and city of Baton Rouge.

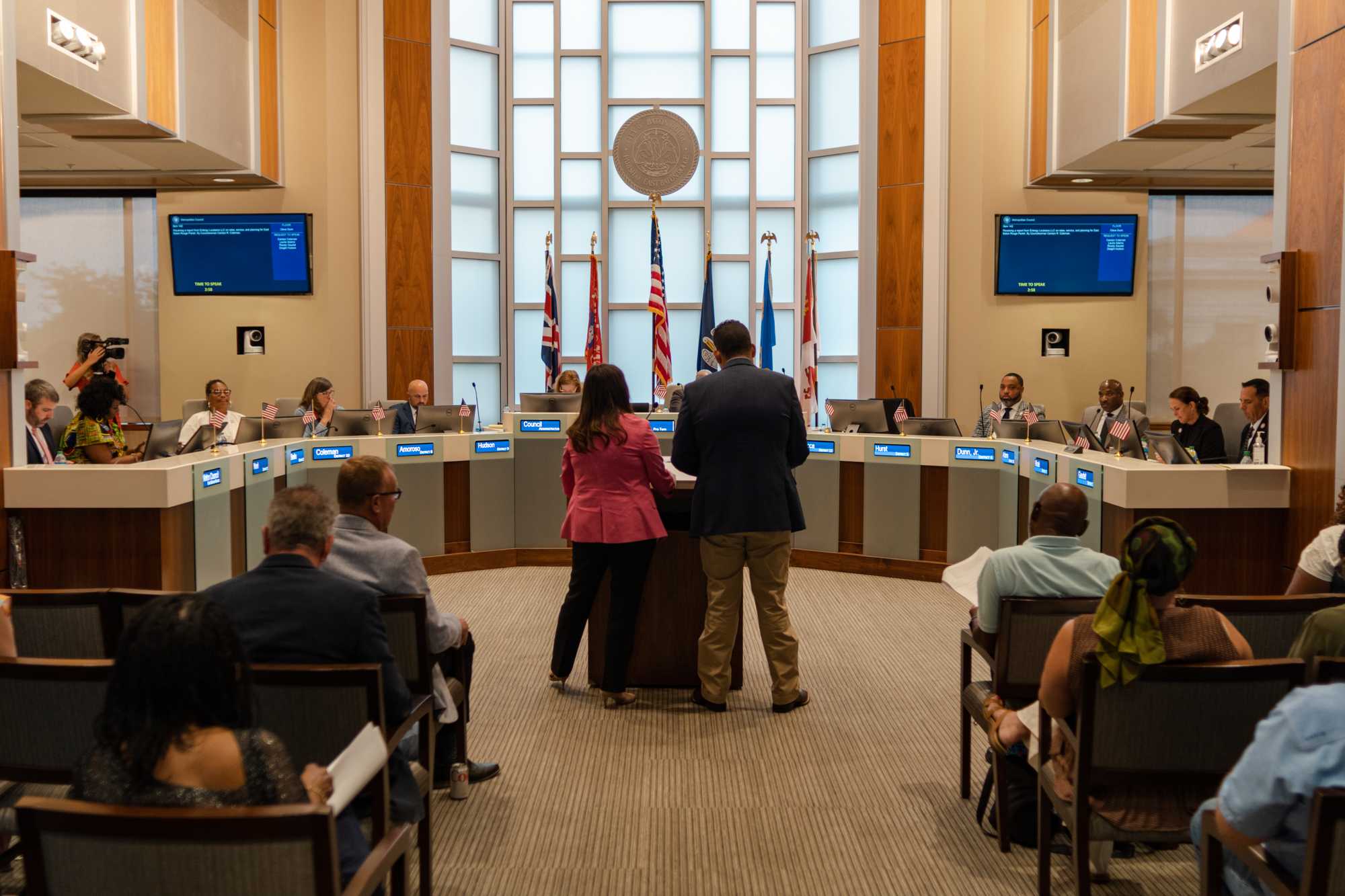

At Wednesday’s Metropolitan Council meeting, constituents and council members gathered to express their disappointment to Entergy representatives Michelle Bourg, vice president of customer service, and Traye Granger, senior manager of distribution operations.

“In the last six months, we’ve probably had 12 electrical stoppages,” said Baton Rouge resident David DiVincenti. “I don’t know what the problem is … but it’s never been this bad.”

The tenor of the room was one of exasperation. Stories of downed poles and faulty transformers were many. Resolutions were few.

Bourg and Granger offered explanations—the heat, the equipment, the challenges of managing a system so large—but their explanations largely fell short for both residents and elected officials.

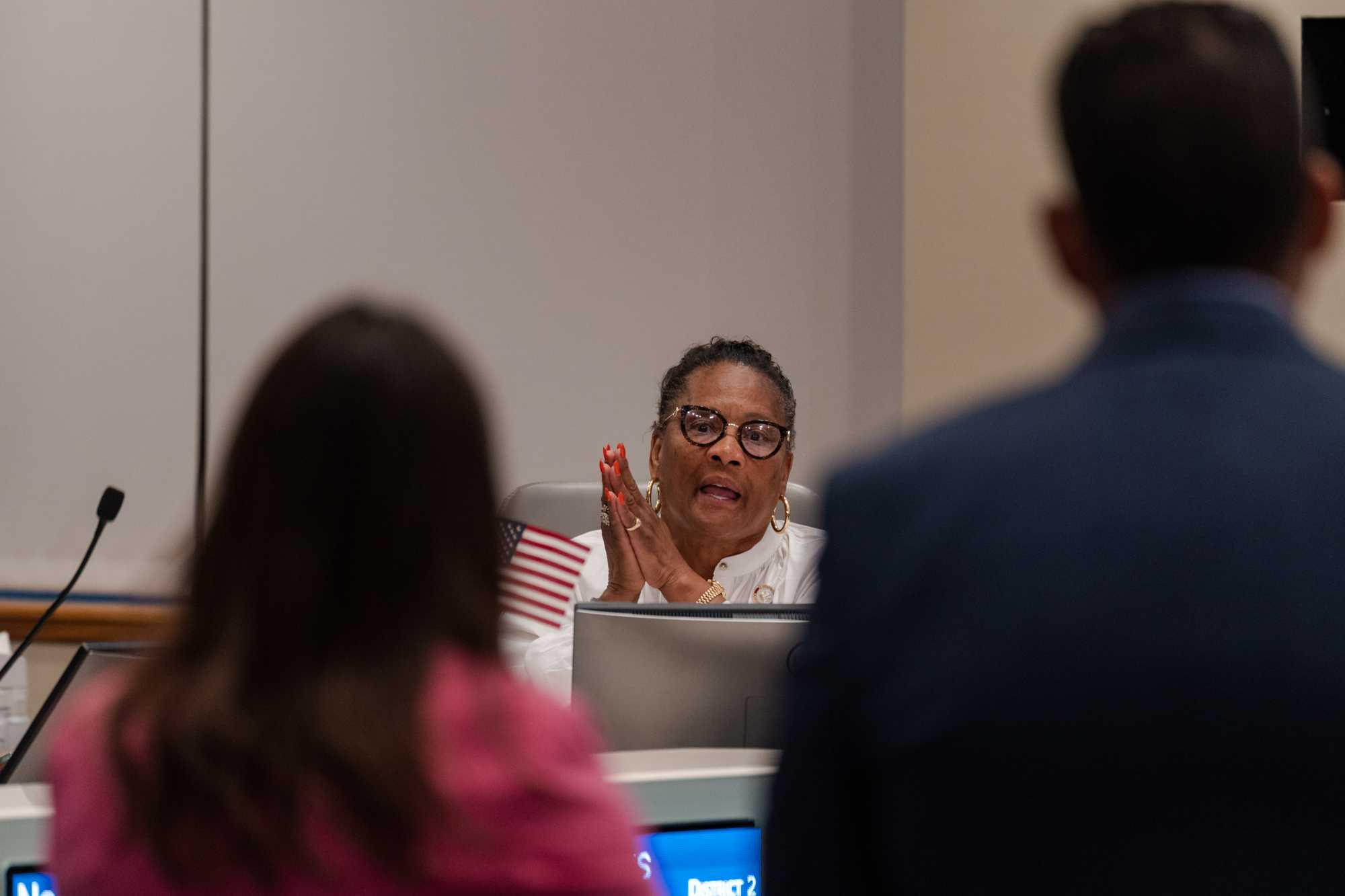

“I just want to know why every time you look around the electricity is off, but the bills are still coming?” asked councilmember Carolyn Coleman, who ran over her allotted time in a heated push for answers that did not arrive.

Come heat and come outage, LSU’s fall semester lurches forward. With a bump and a grind, new days will come, but days like these beg the question: What will be next?

Claire Sullivan and Matthew Perschall contributed reporting to this article.