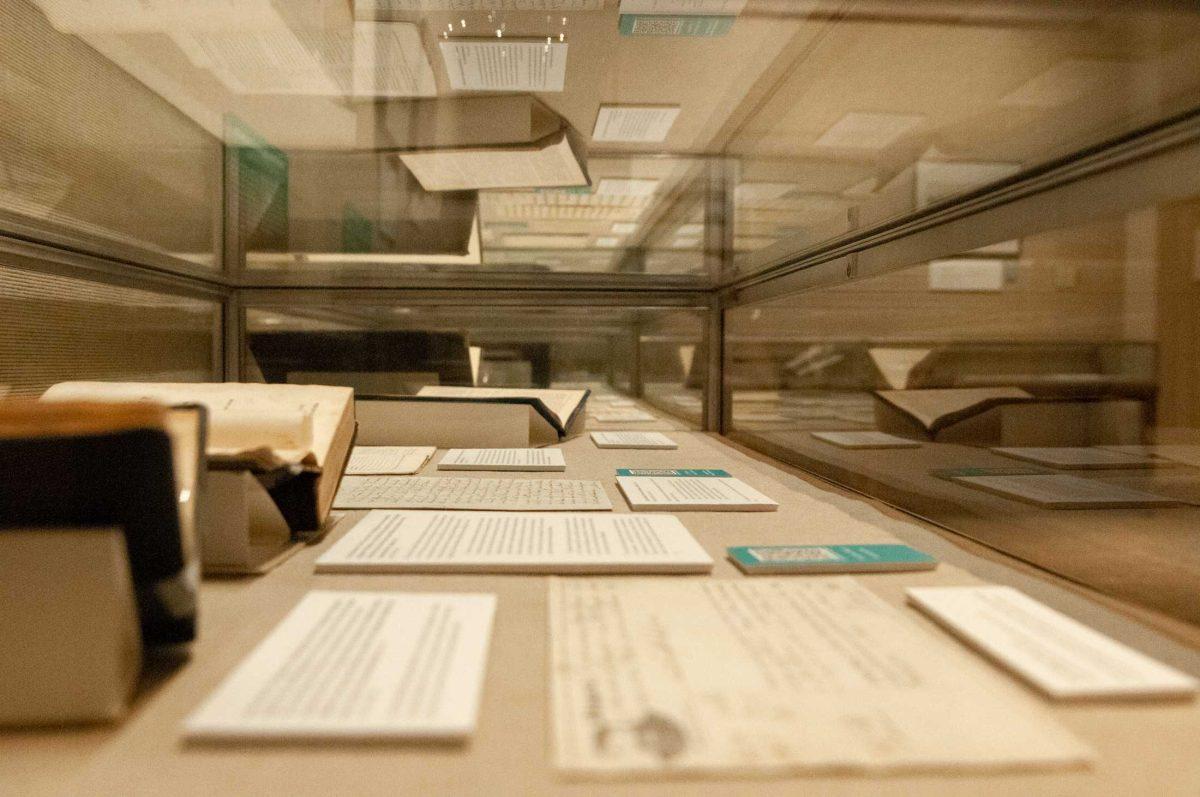

Some of the casualties of Louisiana’s sinking coast could include the shelters of its history and culture — libraries, museums and galleries.

But with the help of LSU researchers, information repositories in Louisiana and around the country may be able to better prepare for mounting risks from climate change.

With support of a roughly $473,000 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services in Washington, D.C., an interdisciplinary team at LSU is developing a risk assessment scale that will help institutions understand their vulnerability to different climate risks like storm winds, flooding and extreme heat.

The team will analyze a group of 92,000 cultural heritage institutions across the country, including art galleries, zoos, children’s museums and more.

This will be done using geographic systems analysis, which means “instead of looking at physical maps, you’re overlaying data on top of maps so that you can see how things interact,” explained Edward Benoit III, one of the researchers and an associate professor in the LSU School of Library and Information Science.

The research will be made publicly available, which means that even if an institution isn’t on the list, it can look to a neighbor for risks, said Benoit, who is the coordinator of LSU’s cultural heritage resource management program.

This project combines expertise from information science, geography, climatology and more—an interdisciplinary approach in which its researchers take pride. It will also involve 25 undergraduate and graduate students from across fields.

“The world of today asks for scientists to answer some of the most difficult questions the human race has ever been faced with,” said Jill Trepanier, one of the researchers and an associate professor in the LSU Department of Geography & Anthropology. “The only way to do this is with teams of people from different backgrounds answering questions with different approaches and ideas.”

Trepanier, who is an extreme weather expert, said Louisiana is especially impacted by threats like land subsidence, rising seas and hurricanes. Areas along the coast and the Mississippi River are particularly vulnerable, she said.

Louisiana has lost about one-quarter of its wetlands since the 1930s, a landmass equal to the size of Delaware, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. This puts cultural heritage institutions in coastal parishes at heightened risk.

And the state has already dealt with major archival losses from extreme storms. About 1.5 million books and manuscripts at Tulane University were submerged in floodwater when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, according to the university’s library.

“[Louisiana’s] culture and the resources to support that culture are being threatened by these major events, so we want to identify the areas that are most ‘at risk’ and help them understand if resources actually need to be moved,” Trepanier said.

Moisture was the most commonly cited source of damage for cultural heritage collections, according to 2014 data from the Heritage Health Information Survey.

Humidity is an often-overlooked risk to archives, according to Jennifer Vanos, a collaborator on the climate risk research and an associate professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability. Even low humidity can have detrimental effects on repositories over long periods of time, she said.

“This is especially relevant for locations with already high humidity that lack proper air conditioning, or in the face of long-term power outages wherein the archives could get ruined without proper air conditioning,” Vanos said.

For Louisiana institutions, these challenges are familiar. Being able to quantify the climate risks they face, though, will help them come up with plans and fight for the funding to see them through, Benoit and Trepanier said.

“Many times, people are unable to clearly articulate the risks…we want to help provide them with the explanation so they can advocate for themselves with more back-up,” Trepanier said.

Institutions along Louisiana’s coast have disappeared in recent years, but this research could help, Benoit said.

“These cultural heritage institutions hold our history, and there’s a much more important societal potential loss there,” Benoit said. “Once things are damaged and destroyed, they don’t come back.”