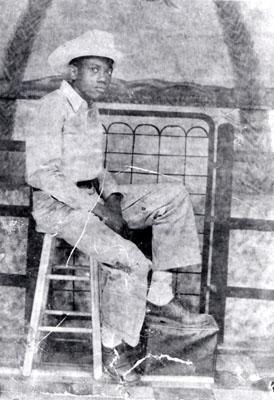

As a black man persevering in the sweltering racial oppression of deep south, 1960s Louisiana, Wharlest Jackson was moving up in the world by most measures.

A veteran of the Korean War, he was the father of five children, loved a caring wife and he’d just been promoted to chemical mixer, a position never held by a black man at the Armstrong Tire and Rubber Company in Natchez.

His wife, Exerlena, begged Wharlest not to take the job, though the accompanying raise of 17 cents per hour would allow her to quit work and focus on family matters.

Exerlena had heard the stories of black men killed, beaten and maimed by angry white people and even law enforcement in Natchez and Vidalia, La., just across the river. Years earlier, they nursed their friend, and Wharlest’s co-worker, back to health after he was nearly killed by a bomb likely planted by the Klu Klux Klan, who terrorized the black community constantly at the time.

As racial reforms began spreading across the nation in the 1960s, Natchez, Vidalia and nearby Ferriday, La., remained unyielding bastions of oppression.

Exerlena feared the price would never be worth any pay raise.

But, Wharlest took the job and only days later as he was driving home from work, the weight of his hand fell on his old truck’s turn signal.

Seven blocks away, the windows rattled in the house where Exerlena was resting and she immediately knew.

She would later tell the Concordia Sentinel newspaper, upon hearing the explosion she shouted: “Oh, Lord, that’s Jackson. That’s Jackson!”

A bomb placed under the driver side of Jackson’s truck mangled the vehicle and Wharlest’s body. He was killed instantly.

The murder drew the nation’s attention and notice of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, who have jurisdiction when an explosive is used in a crime.

The FBI probed, but the case grew cold. The spotlight dimmed and eventually faded. Outrage simmered into acceptance.

The years passed, Jackson was remembered, but nobody was ever brought to trial in his murder.

Such were the times in the deep South.

The question of justice remains unanswered, and for many years unasked. But now, new efforts championed by both local journalists and federal agents aim to put closure to this racially motivated murder and many like it.

It’s a question all too common in Louisiana with six racially motivated cases now being reexamined through the FBI’s Cold Case Initiative.

Federal investigators launched the initiative following the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007. Named after a young black teenager from Chicago killed while visiting family in Mississippi in 1955.

Since then, the FBI has reopened 111 cases totalling 124 victims. All but two of these victims are black. At least two dozen of these murders occurred in Louisiana and Mississippi mostly during the ‘60s.

Prosecutors have closed 79 cases thus far, with one federal prosecution. Three of these cases come from Louisiana and are closed because contemporary federal investigators find the “subjects” of the previous FBI investigation have passed away or there is insufficient evidence to continue.

“We do care, but I have to stress there are limitations we face,” said Heith Janke, supervisory special agent for the FBI. “People continue to die, but until they are all dead, there’s a chance.”

Time is an unrelenting obstacle in these investigations, causing investigators to nix 47 percent of their cold case inquiries because all the original suspects are deceased.

Even when people are still living, Janke said, it is extremely difficult to obtain any information that can withstand judicial scrutiny.

Now the FBI is racing against the passing days to complete or close about 30 remaining investigations, Janke said.

Though there isn’t a bounty of hope for solving these aging murders, there has been some progress in the Ferriday area, championed primarily through the Concordia Sentinel editor Stanley Nelson.

Nelson, whose coverage made him a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in local reporting, isn’t the first person one would expect to out-investigate the FBI. He’s as soft-spoken, polite and unassuming as the small, weekly newspaper he runs in Ferriday.

While he may lack the resources of federal investigators, he makes up for it with tenacity and has devoted the past four years to shedding light on the murder of another Concordia parish-area black man.

“I don’t know if I have anything more [than the FBI],” Nelson said. “But what I do have is a huge desire to try, to give up whatever it takes, to go down any road to get. It’s a matter of how important it is to you.”

Frank Morris played a special role in 1960s Ferriday as a successful business owner and black man. He owned a small shoe shop, where for a quarter of a century, he ran an honest trade repairing and selling shoes.

His success would unfortunately lead to his downfall.

In 1964, as Morris was sleeping in his shop, he heard a ruckus outside. When he approached the door, a man with a shotgun prevented him leaving, while another poured liquid across the front of his shop. They set his shop ablaze and retreated into the night.

The shop exploded into a fireball, sending debris into the street and setting Morris on fire. He was able to make it out, but not before the fire had taken its toll.

Once at the hospital, witnesses say every inch of his body was charred aside from the bottoms of his feet. He persisted in agony for nearly a week before he died. He never told his trusted friends or police who he saw in front of his shop that night.

Federal investigators again probed, but, like Jackson’s case, ultimately failed to find Morris’ assassins.

Nelson often tells people he thinks he would have liked Morris, and the motivation for years of digging on a 47-year-old murder is simply empathy.

“One thing is just the general human question of how can a human do this to another,” Nelson said. “Frank Morris was a good, hardworking man, he contributed to his community, he was honest, he worked very hard for what he had and probably had to work a lot harder to get what he had because he was black.”

With the help of investigative reports from the FBI’s initial investigations, Nelson has pieced together a narrative and in the process uncovered much about Ferriday’s dark past.

Like many southern towns in the south, Ferriday was an unwelcoming place for blacks in the ‘60s. There was nowhere to turn for the black population as even law enforcement was brimming with evil.

Nelson is also working to shed light on other cases from the area while continuing his normal duties as the paper’s editor.

Much of Nelson’s work on the Morris murder has illuminated the racial oppressiveness of law enforcement with no character personifying this better than Concordia Parish Sheriff’s Deputy Frank DeLaughter.

Legend of DeLaughter’s merciless brutality and racial hatred grew as tall as the 6 foot, 4 inch deputy and in the black community, paralyzing fear of “Big Frank” carried infinitely more weight than his 250 pound frame.

Nelson’s investigations have linked DeLaughter to Morris’ murder and shed light on how criminals intimidated the city of Ferriday from positions of authority.

“What really surprised me a lot is this criminal element that was in control was really quite powerful and intimidating to [the people of Ferriday],” Nelson said.

Nelson’s investigations have also led him to Author Leonard Spencer, a Rayville man in his 70s, who admits being in the Klan in the 1970s, but told the Sentinel he had never heard of Frank Morris. Spencer has been implicated in the murder by family and ex-family members who say Spencer has, on multiple occasions, confessed to the crime.

In January 2011, for the first time in 47 years, a suspect was named in the Morris murder and it was on the front page of the Concordia Sentinel.

Now, and not necessarily tied to Nelson’s investigations, a Concordia Parish Grand Jury has been summoned to probe into the murder.

“If nothing else this will at least provide a historical record of all we could do,” Nelson said. “It records fact, of who he was, what a terrible thing happened to him and what theories are out there for how the murder occurred.”