When Cajun Dance instructor Roland Doucet started out as a radio DJ in the mid-80s, it seemed like Cajun music was a dying art.

One day in 1988, he was approached by record producer Floyd Soileau, whose prediction for the genre’s future was bleak.

“He told me early in my career that this music was dying, it was just a matter of time,” Doucet said. “He told me he hadn’t signed any new people in 15 years.”

But Soileau’s prediction turned out to be wrong.

Recent years have ushered in a proliferation of contemporary Cajun artists — including Hunter Hayes, Kevin Naquin, Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys and Wayne Toups — who have helped introduce a new generation to swamp pop and zydeco. And there are plenty of local establishments where the young and old alike gather on Saturday nights to kick up la poussiere at a fais do-do.

A Vinton native, Doucet was first introduced to Cajun music and culture by his parents.

“My father played fiddle for 45 years,” he said. “My mom went to the dances and of course couldn’t dance with my dad because he was playing. So as me and my brothers reached her height — with me, I was 13 — she taught us how to dance so she’d have a ready-made dance partner.”

But Doucet didn’t always know he wanted to be a dancer. When he was 13 years old, he aspired to be a musician like his dad, and he asked his father what instrument he ought to play.

“He said to me, ‘Why do you think you ought to play an instrument?’” Doucet said. “And I said, ‘Well, everyone in the family seems to play music, so I figured I need to learn.’ And he said, ‘Son, if you’ve got rhythm in your feet, don’t develop it in your hands. Would you rather hold that cold instrument on the bandstand or that warm woman on the floor? And I said, ‘I think I just made up my mind.’”

In the end, the dance lessons from his mother paid off.

Doucet is now entering his 29th year as a Cajun dance instructor for LSU Leisure classes, where he teaches his students how to waltz, two-step and jitterbug.

He started teaching the leisure classes because of his passion for dance and his desire to feed the Cajun music scene in the Baton Rouge area. He described the relationship between Cajun musicians and Cajun dancers as symbiotic; without one, the other can’t stay alive.

“I felt like I could contribute [by teaching dance] since people would stay dancing here locally,” he said. “Because that way, the bands would keep playing. We have more people that’s recording now than we ever did … There’s no doubt it’s on an upswing.”

Political science senior John Nickel signed up for Doucet’s beginner dance class as a way to get in touch with his Cajun heritage.

“I’ve been around Cajun culture all my life. Growing up in Crowley, I went to Rice Festival and the Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival every year and always listened to the music,” Nickel said. “Always thought it was the dorkiest thing growing up. But as I got older, I saw how the culture of Louisiana is so different, and how much everyday life — like going to get crawfish or going to listen to Cajun music — that’s not necessarily what everybody did growing up.”

Nickel said his appreciation for Louisiana culture deepened after taking a cross-country road trips with a close friend. Driving across the South was like an epiphany for Nickel, who said the experience taught him just how remarkable and distinctive Cajun culture is.

“There’s so many different ways to explore it,” he said, with a rare level of genuine enthusiasm and earnestness. “It’s not like you have to learn about your heritage by taking a course; you can go to the Shrimp and Petroleum Festival or go to Mardi Gras and chase chickens … You’re drinking, you’re having a good time, but you’re learning.”

Another way University students are getting in touch with their Cajun heritage is through learning the language of their ancestors — Cajun French.

Amanda LaFleur, who lobbied LSU to teach a course in Louisiana French as an undergrad in the late 1970s, currently teaches Cajun French at the University.

LaFleur serves on the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) Executive Council and aims to instill a sense of appreciation for Cajun French in each of her students.

In their second year, LaFleur’s students have to interview someone in their community and collect a story, recipe or a personal narrative in Cajun French.

“What I always find interesting … has to be the sense of satisfaction I see when the students have done their projects,” LaFleur said. “I think it’s those human connections that they make that mean the most.”

For some, the human connection is in the form of family.

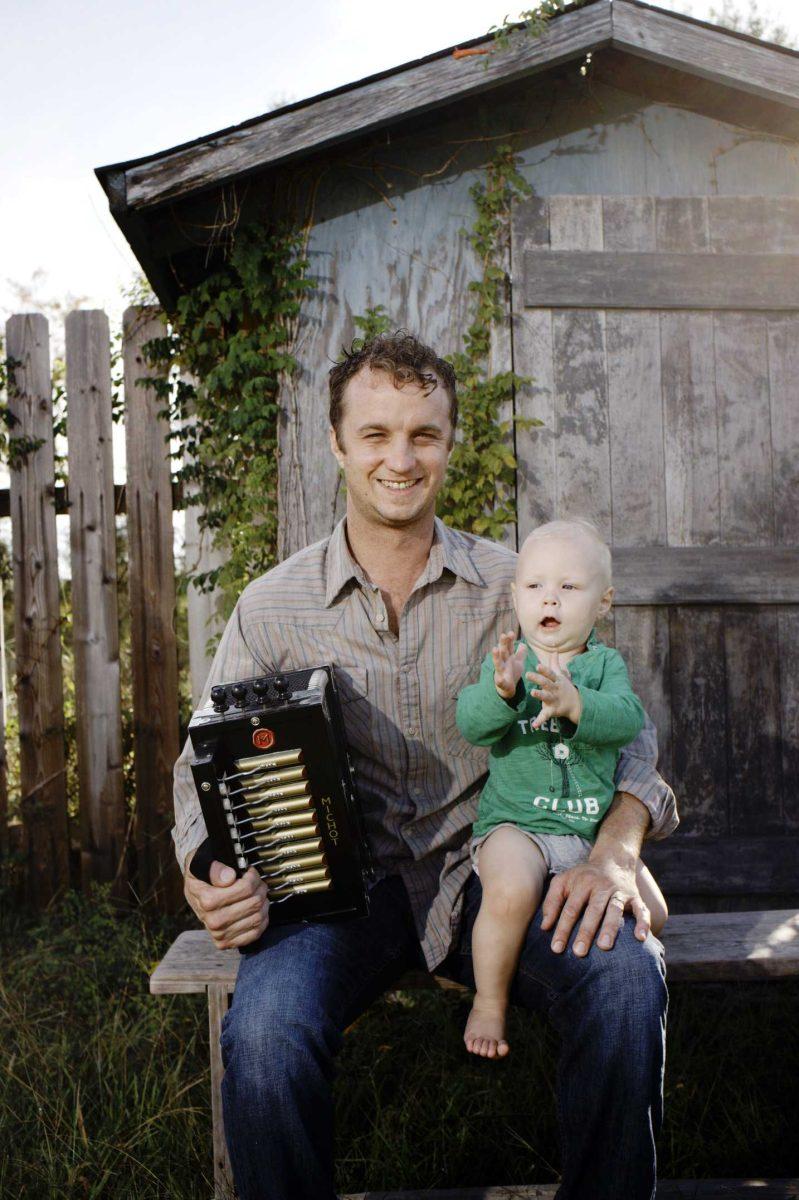

Louis Michot, the founder of the Grammy-nominated Lost Bayou Ramblers, grew up surrounded by Cajun culture and music — his father and uncles played traditional Cajun music as Les Frères Michot.

“I was raised in a Cajun French band,” he said. “When I was real young, starting when I was maybe five years old, we’d go to a lot of their gigs, and I joined the band at 16. I didn’t even play the stand up bass when I started playing; they basically threw me on stage. I was a guitar player, and they needed a bass player. So I learned.”

But it wasn’t until he grew older that he was inspired to learn Cajun French and get in touch with his heritage, he said.

“When I finished high school, I traveled to Ireland with my best friend. I loved Irish music, and I was really just fascinated with Ireland,” he said. “When I was there, I could see what I’d just left and how much I actually had back home. I could see much more clearly how important and how beautiful Louisiana was. I got back and realized I wanted to learn French, and I wanted to learn the fiddle.”

So Michot traveled north to study French at Université Sainte-Anne in Nova Scotia, Canada. Learning on the fiddle he had inherited from his grandfather, he taught himself how to play while hitchhiking through Canada for three months.

“I just played on the streets, and I learned how to speak French,” he said. “The language holds so much of the history — there’s much more depth when you can understand the culture in its own language. And so learning French and then learning Cajun French on top of that was just like putting it all together.”

For Michot, “putting it all together” meant starting a Cajun band of his own with his brother in 1999.

The Lost Bayou Ramblers — who have toured across the U.S., Europe, and Canada — began as a traditional Cajun band for a decade and have grown stylistically since then, incorporating rock and other musical influences to create their own distinct sound.

Michot said his goal is not only to preserve traditional Cajun culture but also to add to Cajun culture by making new music inspired by the songs he grew up playing.

“My culture inspires me … I guess I feel like I’ve been handed the music; it’s just something that came to me as a blessing. And I want to give back to that,” he said. “We’ve really been inspired to write original tunes for our new generation … [Cajun culture] is definitely something that I something that I want to keep relevant, that I want to make more relevant for younger generations.”

Like Doucet, LaFleur and Nickel, Michot said Cajun culture is alive and well

today.

“Sooner or later, people realize how important these things are,” he said. “I think it starts with people realizing that it’s a part of them … Cajun culture keeps relevant because it keeps reinventing itself; it seems like it’s always about to die, but it keeps staying alive. I think that the young generation is a big part of the resurgence of Cajun culture, and I think with every generation, there’s going to be a lot of people that realize that it’s theirs, they own it, and it’s up to them to continue it.”