During last week’s closely watched presidential debate, President Barack Obama criticized Mitt Romney’s tax plan, saying his proposals would disproportionally benefit the wealthy, unfairly burden the middle class and significantly increase the deficit.

And after taking a closer look at the math behind Romney’s plan, it appears that Obama was right.

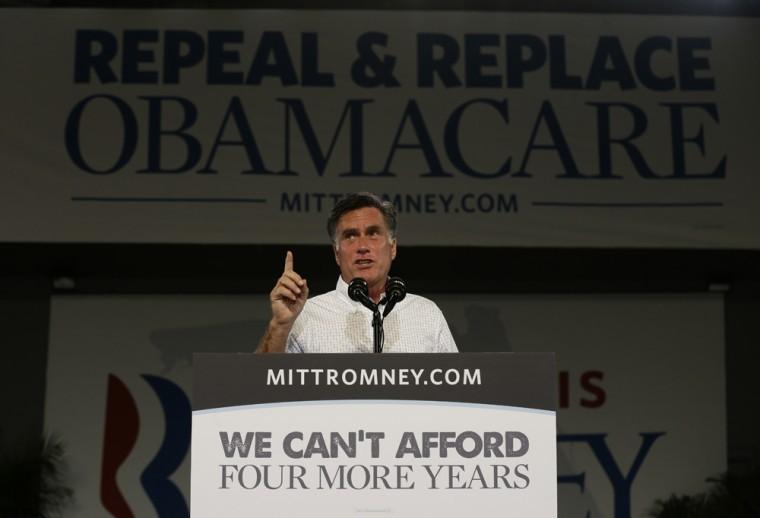

However, Romney vehemently denied the President’s claims, declaring “virtually everything he said about my tax plan is inaccurate.”

The GOP contender insisted he would not raise taxes on middle-income Americans and that he would not increase the deficit.

So what exactly would Romney’s plan mean for taxpayers?

First off, it should be noted that President Obama has no adequate plan to deal with our nation’s debt crisis — but Romney’s tax plan is far worse.

Romney would begin by permanently extending the Bush tax cuts scheduled to expire in 2013. Next, he has proposed eliminating the estate and alternative minimum taxes and imposing an across-the-board 20 percent reduction for all income tax rates.

As Obama and most economists have pointed out, these eliminations and reductions alone would add $5 trillion to the deficit over 10 years.

But Romney has claimed he would be able to offset these reductions through a process known as “broadening the base” — cutting back tax loopholes, deductions and exemptions.

In fact, this “base-broadening” argument is the foundation for Romney’s entire tax plan.

Romney contests that these reductions in tax breaks, in combination with moderately faster economic growth brought about by lower tax rates, will make the individual income tax changes revenue-neutral.

The Republican nominee has taken a lot of heat for not disclosing which loopholes he would eliminate, but he said earlier this week that he would put a $17,000 cap on annual deductions, such as mortgage interest and charitable contributions.

Unfortunately for Romney, however, even if he eliminated every loophole and deduction, it wouldn’t be able to make up for the cost of his massive tax cuts.

According to Brookings Institution economist William Gale, who co-authored a study of Romney’s tax plan for the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, “Romney’s plan doesn’t come close to paying for the $5 trillion.”

As a result of Romney’s plan falling short, the Tax Policy Center concluded that $86 billion of the shared national tax burden would be shifted onto the middle class in 2015 alone. Otherwise, that amount would just be added to the federal deficit.

President Obama perfectly described Romney’s tax plan in last week’s debate: “The fact is, if you are lowering the rates the way you describe, Governor, it is not possible to come up with enough deductions or loopholes.”

Obama added, “It is math. It is arithmetic.”

Because Romney’s tax plan is based on the incorrect premise that he can actually pay for the gargantuan, across-the-board cuts in individual tax rates, there are two possible outcomes.

Either he will further increase the deficit, which he has flat-out refused to do, or he will just have to shift the burden to the middle class.

In a better world, Romney’s plan would be considered nonsense and laughed out of the debate.