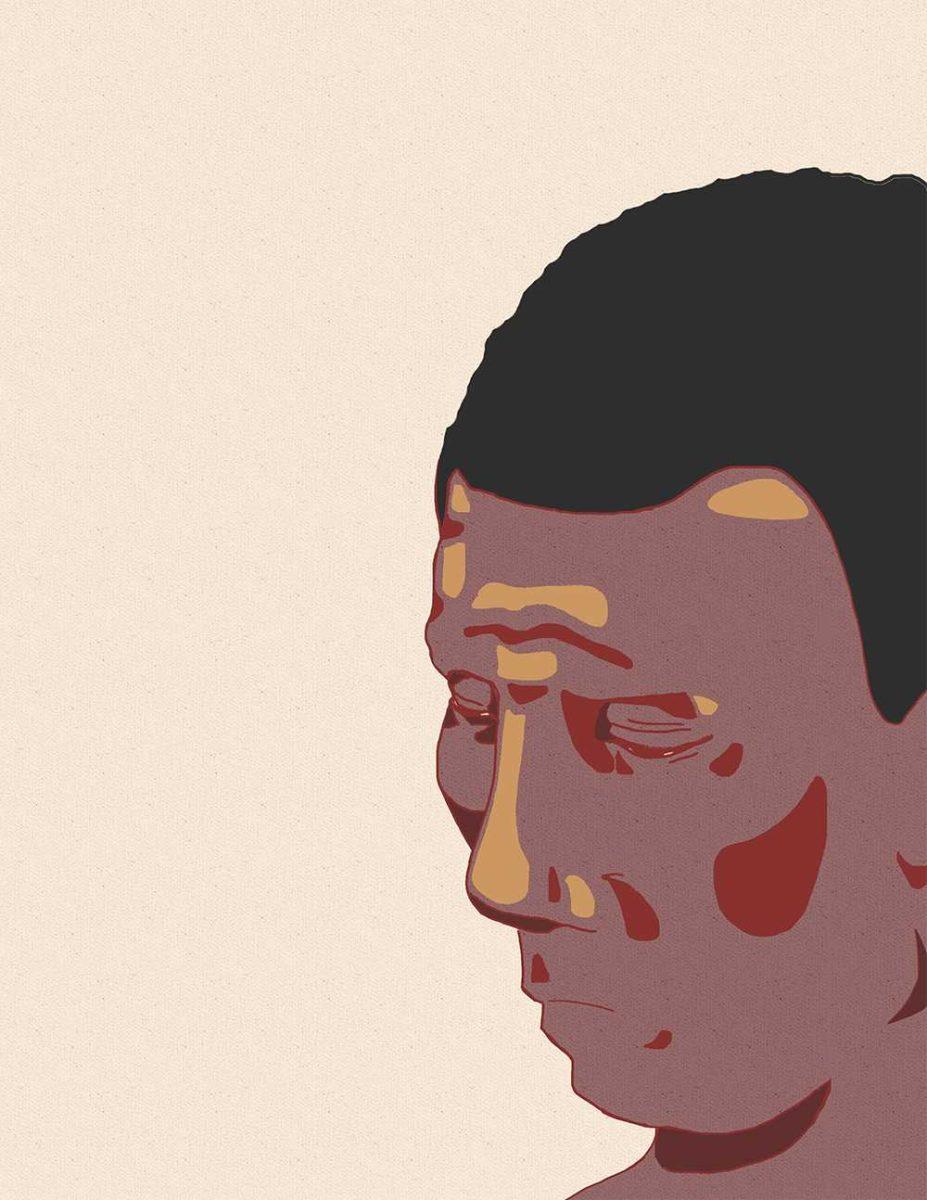

As a sophomore in high school, current LSU wide receiver Armand Williams had only two choices: remain with his mother as they faced a second eviction notice, or enter the home of relative strangers. Armand chose the latter.

For the computer engineering sophomore, the notice was only the latest in a string of difficult experiences. While football acted as a temporary relief from the stresses of school and home, Armand found complete security in the Braud family.

Armand describes his childhood in New Orleans East as fairly independent. His mother, Minnette Williams, provided for the family of four by working 15-hour shifts as the Hyatt Hotel’s banquet manager. Her long hours often left Armand alone to care for himself.

“I could handle myself,” Armand said. “She gave me that trust because she knew that I understood her hard work was for my benefit.”

However, after Hurricane Katrina destroyed their home in August 2005, the Williams’ finally settled in Slidell following an evacuation stint in Nashville, Tenn.

After moving into an apartment of their own, Armand said he and his mother struggled financially. Within months they received their first eviction notice.

“At first I thought, ‘Oh, my mom’s got this.’ She’d always come through before,” Armand said. “But as time went on, I knew I had to step up my game [and contribute].”

Even with his mother working long hours and Armand himself working three jobs, the second eviction notice was the breaking point.

Armand found a confidant in the form of his chemistry teacher, Theresa Braud, who recognized his need and responded.

A mother of ten, Theresa’s caring nature prompted her to make consistent efforts to connect to Armand, despite his initial reluctance, he explained.

“Mrs. Braud would ask me how my day was every day. It was definitely more her reaching out to me because I didn’t feel like my teacher had to know what I was doing back home,” he said.

However, at home, money was so tight, he said, there was often no food to eat. Armand tried to make do by eating breakfast and two lunches at school, but intensive calorie-burning workouts made it difficult.

“I felt so bad,” he said as he slowed his fidgeting hands. “I felt like I was a burden, that I was [holding my mom] back.”

Theresa responded to Armand’s crisis by including him in her family dinners, which Armand described as immensely comforting.

“Mrs. Braud didn’t want to force me there, but it was just a warm and loving environment. It was safe and not stressful,” he said.

As time progressed, Armand gradually spent more and more time at the Braud household.

“Armand was always over,” his foster sister, pre-pharmacy sophomore Rachel Braud said. “Mom didn’t let us know the full story, but it all began with the dinners. Eventually he was spending the night at our house, driving to and from school with me, and doing everything with our family. One day we just decided to make the transition permanent. He was no longer just a guest.”

For Armand, the decision was a little more difficult. “I didn’t want to leave my mom,” he explained. “But after thinking about it, I realized that if I was to leave, maybe she could focus on herself. She wouldn’t have to worry about me too.”

Throughout Armand’s struggles at home, football not only continued to offer a steady sanctuary, but also proved to be ticket to a better future.

Armand discovered football at the age of four while playing for a local park league called the Gretty Saints.

“That was when I fell in love [with football,]” he said as he vividly described the peewee-style games.

He played with the Gretty Saints for almost ten years, but

in his last season in the league he found himself in the midst of the storm that transfixed the nation.

While waiting for the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina to settle, Armand and his mother relocated to the suburban town of Hermitage, Tenn. where he enrolled in a local middle school. The school community warmly welcomed Armand as both a victim of the storm, but also as an athlete.

There, Armand realized the shortcomings of New Orleans public schools.

“In the school system I was in before, I was set up to fail. The teachers couldn’t teach and parents were in and out. Up [in Tennessee] I saw what kind of education I could have.”

When Armand transferred to Slidell High School the summer before his freshman year, he immediately threw himself into football.

These football games and practices acted as stress relievers, Armand said.

“I was still struck by what we lost in Katrina,” Armand said. “When I put on my pads, the worries melted away. I didn’t have to think about the real world.”

But the real world did not go away. In addition to school and practice, Armand worked three jobs to help with the rent.

“I would go to school from 7 a.m. until 8 or 9 p.m., and then head to Rouses [grocery store] for a three hour night shift,” he said. “I felt like if I didn’t help, no one else would. I just thought I could put a hold on the eviction.”

Even with this combined income, Armand constantly worried if he’d have a place to live or where he would play football, he said.

When approached by his teachers, coaches and principal, Armand would shrug off their questions with reassurances of “I’m doing fine.”

“The Armand we knew was the ‘I’m fine’ Armand. We had no idea that he was struggling at home,” Rachel explained.

Despite the stresses of home, as early as his freshman year Armand started receiving letters expressing interest in his football career from colleges across the nation. He savors the memory of hearing from his first college: Tulane.

“At first, I thought it was an academic scholarship,” he said with a grin, “but then I realized that my playing football could get me into college. I have [had] never even thought about college before. I’m the first in my entire family to go to college. Period.”

As more colleges began to show up at practices and games, Armand developed a three-part list of what he wanted out of a school: first, a good academic environment; second, the potential to win a championship, and third, a location that wasn’t too far from home. LSU fit all three.

But even after committing to LSU, Armand expressed worries about college.

“I had second thoughts all the time. I looked at my family history and wondered if I could pull off college. But I also saw an opportunity to rise above that history. I got greedy and ran with my opportunity,” he said.

“Armand is the most persistent, most determined person I’ve ever met,” Rachel said in a pride-filled voice. “I think that’s why he’s so successful and made it this far.”

Today, football remains an escape from the stress of school or hiccups in life.

“It’s my therapy. I have fun doing it,” he said while describing his expectations of starting next season.

The Braud family also continues to be a source of comfort and community for Armand, who agrees that his “home” is with the Brauds.

“It’s a different relationship [from my biological family],” he said. Contrary to his independent childhood, Armand became a part of every aspect of the Braud family’s life.

By living with the Brauds, Armand was able to enjoy a variety of new experiences.

“I would go with them to the store, movies and church,” Armand said. “In fact, the first time I ever went Christmas tree shopping was with their family. It was the first time I had ever bought a Christmas tree. I felt like a kid.”

Despite Armand permanently residing with the Brauds, he continued to visit his mother’s apartment, which was only two blocks away from the Braud’s home, every day.

Armand explained that although his mother wanted more control of the situation, Minette accepted the fact that her busy work schedule didn’t allow it.

Meanwhile, the Braud family tried their best to accommodate Armand’s unconventional family situation.

“We understand he has his [biological] family and we don’t want to take that away from him,” Rachel said. “He can still be a part of our family without officially leaving his own.”

As his time between the two families overlapped, he began to see the Brauds as his own family, referring to Rachel and two of her siblings, Amy and Michael, as his brother and sisters.

“Armand is a brother to me,” Rachel said emphatically. “Anything I would do with my family would include Armand. I have 10 brothers and sisters, not nine.”

Armand traced his love for the Braud family back to a deep connection to Theresa.

“Mrs. Braud opened up to me. I found out she had been adopted. It made me think ‘She was almost someone like me,’ and it felt like we shared something in common,” he said. When describing Theresa, Armand struggled to express himself. “I wish I could come up with a word beside caring. Caring seems less than the word she is. That’s how important she is to me. She’s so much more.”