Buried in a fold of the Howe-Russell Geoscience Complex is a tiny building alive with faces of the dead.

The LSU FACES — Forensic Anthropology and Computer Enhancement Services — Laboratory is not only filled with desks for its seven employees but hundreds of pictures and molds of recreated faces of missing and unidentified persons.

“We work with law enforcement throughout the state and nation to identify the dead,” said Lab Director Mary Manhein, summing up the lab’s duties.

The lab essentially collects DNA and bone samples from decomposed bodies or unidentifiable bodies and builds an online database for all the missing and unidentified persons throughout the state and nation.

As of Tuesday, there were more than 300 cases in the database.

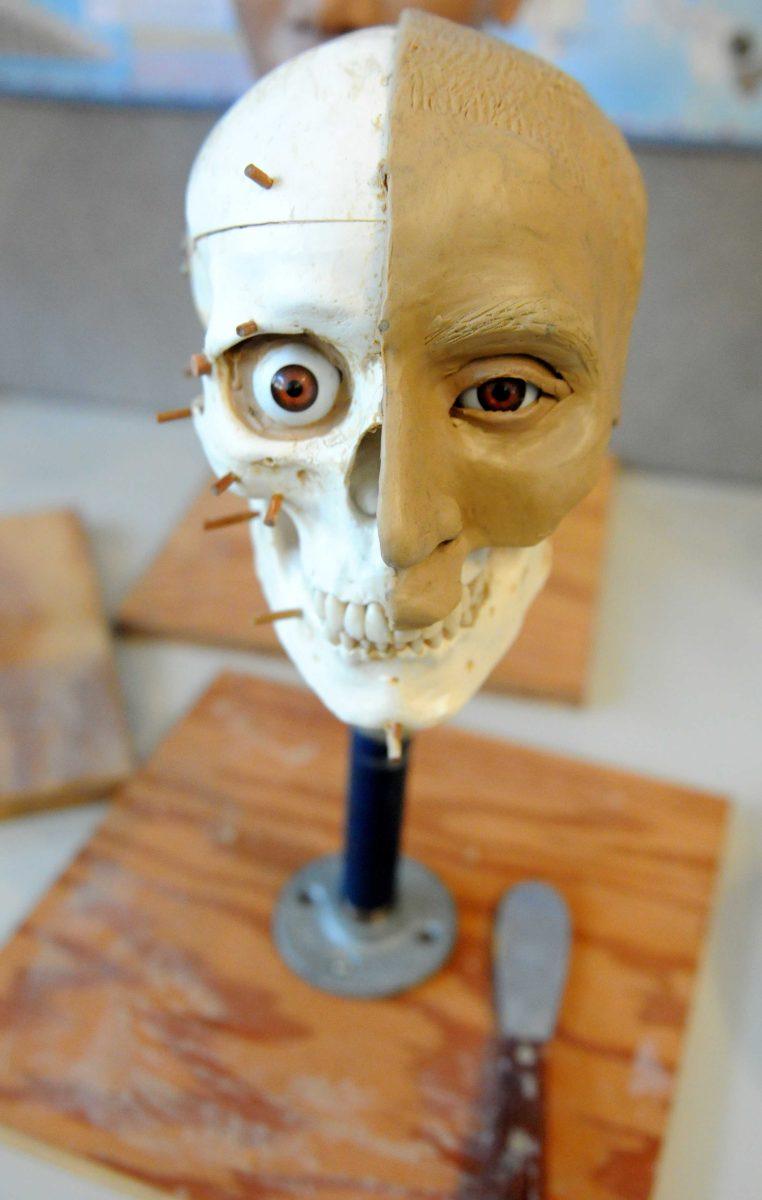

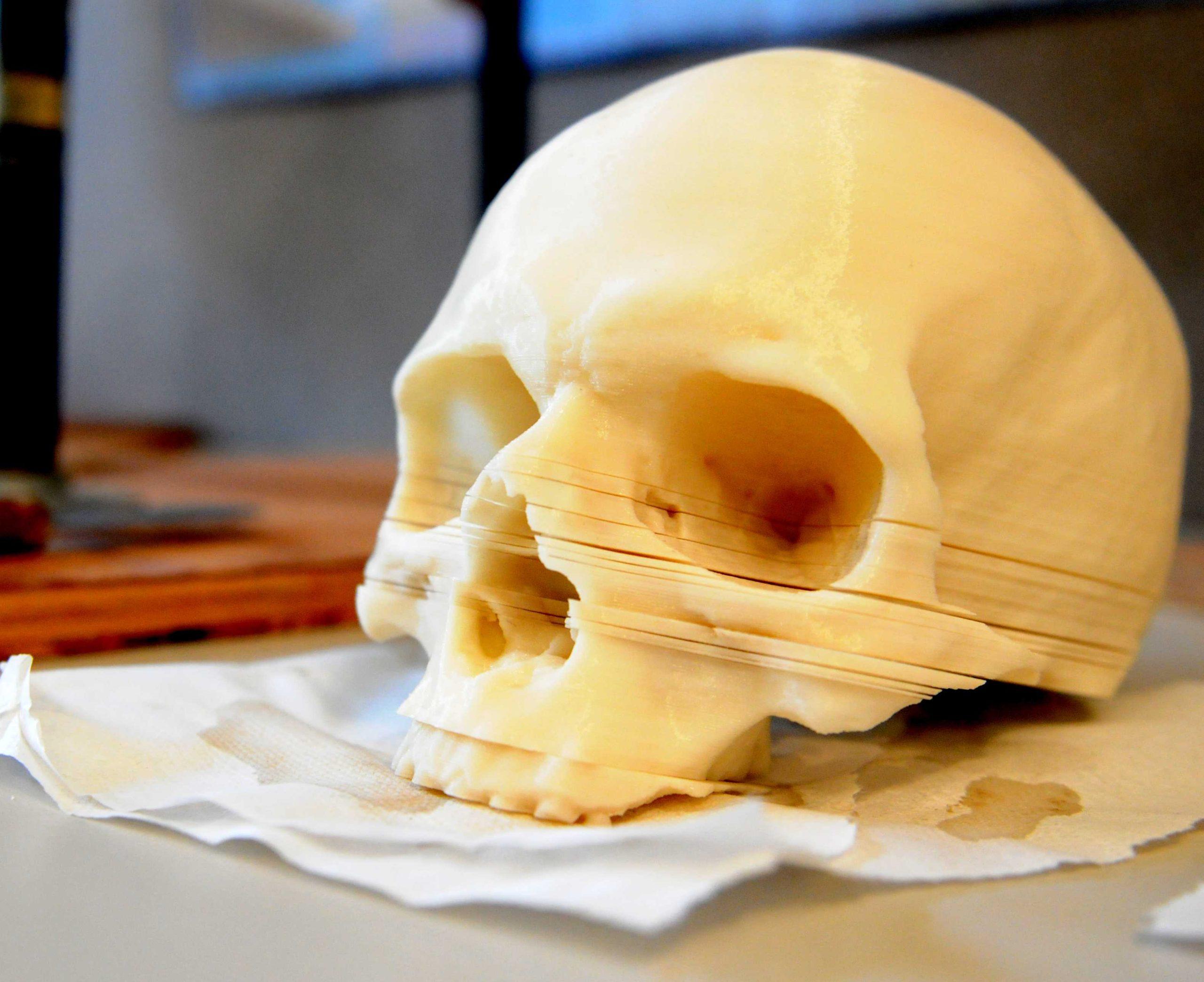

Additionally, the lab does digital and plaster facial reconstructions from skulls, placing images of faces online and on Crimestoppers billboards in an effort to identify remains.

The dirty work of dealing with human remains is done in a “wet” lab inside Howe-Russell that has its own X-ray machine and bone storage.

“We help to make people realize the importance of keeping these remains to help identify them,” Manhein said.

Most recently, the lab identified the remains of Michaela “Mickey” Shunick, a University of Louisiana at Lafayette student, who went missing May 19 as she rode her bike through downtown Lafayette.

Police arrested Brandon Scott Lavergne in July, and he pleaded guilty to killing Shunick and burying her body.

The lab used dental records to identify her badly decomposed remains, Manhein said.

Shunick’s case is one of many. The lab receives between 40 and 50 cases a year and can identify “most” of the remains, Manhein said.

But the lab doesn’t only work with grim murder cases. It also delves into historical projects.

In March, the lab brought history to life by recreating the faces of two Civil War soldiers’ skulls that were found in the gun turret of the USS Monitor, which sunk in 1862.

“We’re really just trying to get a likeness,” said Nicole Harris, anthropology professor and forensic anthropologist. “We want someone to look at a reconstruction and say, ‘Hey that kind of resembles the face shape of my brother.’”

And because bodies decompose, the job stays fresh, Harris said.

“There’s no such thing as an average day,” she said. “Some days we print things in [Patrick F. Taylor Hall on the 3D printer] for facial reconstructions…and other days we’re at crime scenes collecting cases to bring in here to work on.”

While the job can be exciting, it can also be upsetting at times.

“The hardest part is talking to the families,” Manhein said. “It doesn’t matter if it’s 10 days, 10 years or 20 years.”

Harris agreed.

“To sit there and have someone break down and cry to you,” Harris said. “It can be heartbreaking.”

But finally, the sadness can lead to the satisfaction of bringing closure to families and helping law enforcement solve cases, Manhein said.

“There’s no better day than when we can identify someone and send them home,” she said.