Throughout the month of October, I will be reviewing a different horror movie every week. To narrow down the selection, I decided to focus solely on what I’ve deemed contemporary horror classics, films that have come out within the last 10 years that have made a significant impact on the genre, have garnered cult classic status or critical acclaim and are unlike any other horror film released within the past decade.

Some of the scariest things in life aren’t found under our beds, hiding in our closets or lurking in our basements. Instead, true fear comes from the prospect of the inevitable horrors of humanity like grief, loss and failure. But sometimes, just sometimes, a good horror movie can combine these two categories and amplify the scare-factor to a whole new level. In 2014’s “The Babadook,” first-time director Jennifer Kent cleverly represents a depressed single mother’s struggle with loss and parenthood through a clawed, white-faced, top hat-clad monster known as The Babadook.

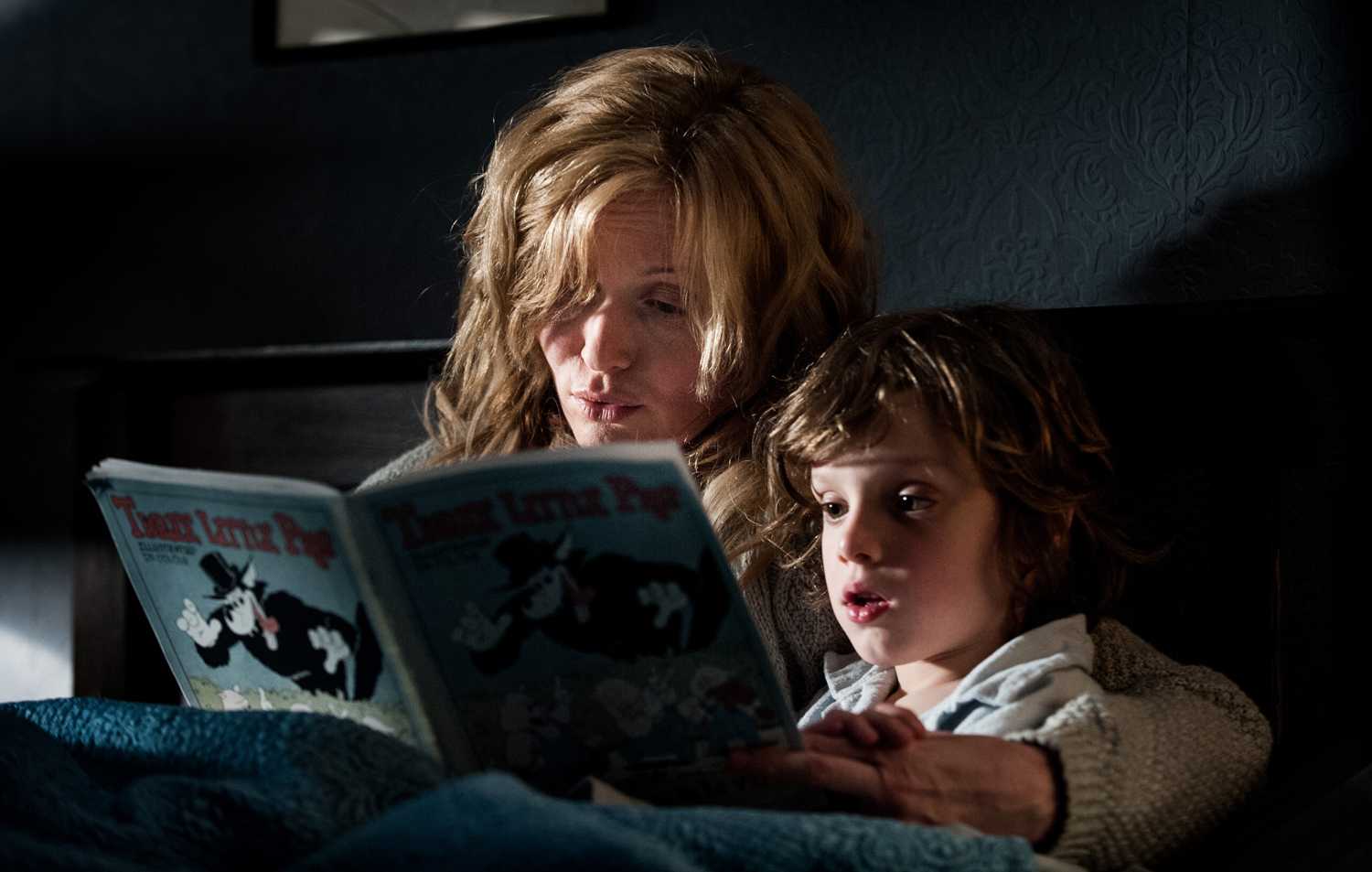

The film begins with a dream. Amelia Vanek (Essie Davis in a visceral tour-de-force performance) is reliving the night she had her son Samuel (a perfectly mischievous Noah Wiseman). Unfortunately for her, that was also the night she lost her husband Oskar in a car accident on the way to the hospital. From the start, we’re conditioned to feel the permeation of loss and sadness seven years later when the film actually begins. She’s never gotten over the death of her husband, and her son’s nagging and screaming which wakes her from the dream suggests she may resent her son for Oskar’s death.

And it’s not hard to resent this particular boy. Samuel is a troubled and high-maintenance child; within the span of a few days, he brings weapons to school and pushes his cousin out of a tree house, breaking her nose. Meant to show what growing up with an emotionally unavailable single parent can do to a child, these actions compose much of the early part of the film.

In harping on these irrational behaviors, Kent shows her skill as a horror auteur. In the beginning of the film, we’re led to believe that — as typical horror films often go — some demonic force will possess the child. But as the film progresses with unease and tension, we begin to realize the real monster is elsewhere.

After reading a pop-up storybook titled “Mister Babadook” that describes a monster who tortures its victims, Samuel can’t seem to get the idea out of his head that The Babadook is real and is coming for Samuel and Amelia.

At first, Amelia is only mildly disturbed, but then strange things happen around the house that lead her to start questioning reality. She finds shards of glass in her food, lights mysteriously flicker on and off, doors open and close randomly and eventually she begins to have visions of The Babadook itself. She tries to burn the book, but it appears at her door reassembled and with new words warning her that the more she tries to deny the existence of The Babadook, the stronger it gets.

The rest of the film teeters between reality and what’s inside Amelia’s head. Even after the film is over, it’s still unclear what was real and what wasn’t. But that’s part of the fun of the experience. We start to question reality, and eventually — like Amelia — we can’t separate between fact and fiction. What’s even more unnerving is we find ourselves able to see why Amelia begins to act irritable and erratic because we’re not unsure that we wouldn’t do the same thing, motivated by grief and an inability to let go.

Serving as an allegory for loss, The Babadook takes over every aspect of Amelia’s life until she’s able to face it head-on and with strength and courage. I won’t give away the ending of the film, but it’s unorthodox for this genre. What happens once you’re finished watching is a cleansing of sorts, a hopeful glimpse into the future.

This film was met with universal critical acclaim when it was released and has since risen to classic status, especially after this summer’s label of The Babadook as a gay icon. There’s really no explanation in that there’s nothing overtly gay about the film, but in doing so it’s appealed to a new audience and has given the film a resurgence.

It is easy to see why critics lauded the film, especially for its originality and psychological horror. Like many of the best horror movies, fear is felt in the tension and not seen in excessive gore or violence. This film is one of the scariest I’ve seen and only because its psychological effects last longer than you would expect.

Technically, the film is near flawless with obvious inspiration from the films of David Lynch and Darren Aronofsky. The set design consists mostly of the dilapidated house Amelia and Samuel live in, and it’s able to mirror their increasingly fragile mental state, providing the film with an aura of unease and mania. The quick cuts interspersed with long takes provide a perfect anomaly, piquing anxiety and interest. And most of all, the physical darkness of the misé-en-scene is able to terrify us in ways I haven’t seen before. With just one film, Jennifer Kent established herself as one of the best working directors in film today.

“The Babadook” is a perfect film to wrap up my October Horror Movie Series. Films like these are the reasons why I love the horror genre. Fear is a powerful emotion and tapping into that in order to tell a story is foolproof when done correctly. Horror is so much more than torture porn and jump-scares; horror should make us think about the state of the world we live in and should help provide insight into different struggles we face as humans.

Nowadays, there are too many of the same horror movies, leading to a general disdain of the genre. I hope with these four films I’ve made you reconsider this stereotype because horror is a wide-ranging and important genre that still provides us with some of the most cutting-edge, controversial and — above all— meaningful films today.