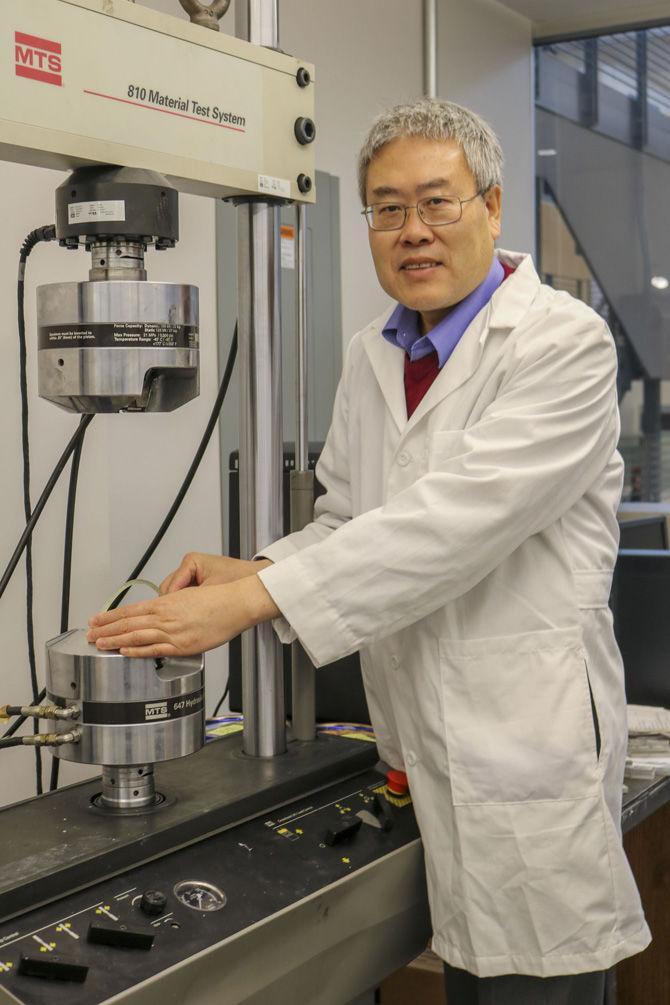

University mechanical engineering professor Guoqiang Li and his team worked for the past eight years to create an asphalt sealant that prevents water from seeping into the asphalt, increasing its longevity.

The earth’s soft soil with its lack of support is one of the reasons why streets crack. The other reason is precipitation, which is what Li’s research is trying to solve. His sealant stops the water from seeping into the pavement because when water penetrates it, cracks become unsealable.

Li majored in civil engineering and taught nine years in pavement and design, but now teaches mechanical engineering.

“We have already sent humans to the moon, but we just cannot solve the problem under our feet,” Li said.

The problem is that the pavement suffers from its thermal properties, according to Li. In summer, all the materials expand, but in the winter all the materials contract. When trying to seal cracks in pavement, a material that behaves in the opposite way is necessary. In the summer, the sealant would need to shrink, and in the winter, it would need to expand.

About 10 years ago, Li started studying shape-memory polymers. Shape-memory polymers behave opposite to conventional physics and, with that, realized that shape-memory polymers were a good material to solve the problem with pavement.

He received grants from the Transportation Research Board and Louisiana Research Board to study shape-memory polymers. On what is now Engineering Lane at the University, he installed two pieces of sealant in 2011. Today, they are still working perfectly, according to Li.

The materials needed a complex process of agitation. The material itself does not work opposite to conventional physics, so, as a result, humans need to agitate it before the installation. This sort of agitation is a form of mechanical deformation. Two postdoctorates on his team in 2011 spent their entire winter break trying to prepare the two pieces of material. Li found this process too complex.

In 2012 and 2013, Li discovered a new material called a two-way memory shape polymer. This material does not need humans to agitate it while the regular polymers had to be. Naturally, it provides the agitation. He disclosed this idea to the University’s intellectual property office and submitted the first patent application in 2014, with a second application following in 2018.

The intellectual property office at the University encouraged him to start a small business in 2016. Hosted in the Louisiana Business and Technology Center, the Louisiana Multi-functional Material Group helps develop two-way memory shape polymers. In 2016, Li received his first Small Business Research Initiative grant from the National Science Foundation, and last year, he received his second one, which they are currently working on.

In December, Texas Transportation Institute tested the sealant in a way that simulated real use, and the material passed their specification. During the spring, the Louisiana Research Center will test the pavement in an accelerated loading facility. Pavement usually takes 20 years to test but, there, it takes three months. They have also been offered the opportunity to test the sealant in Minnesota, which offers a cold alternative to the hot and humid climate of Louisiana.

LSU professor helps improve pavement longevity

January 15, 2019

Professor of mechanical engineering Guoqiang Li provides samplings of his work on Monday, Jan. 14, 2019, in Patrick F. Taylor hall.

More to Discover