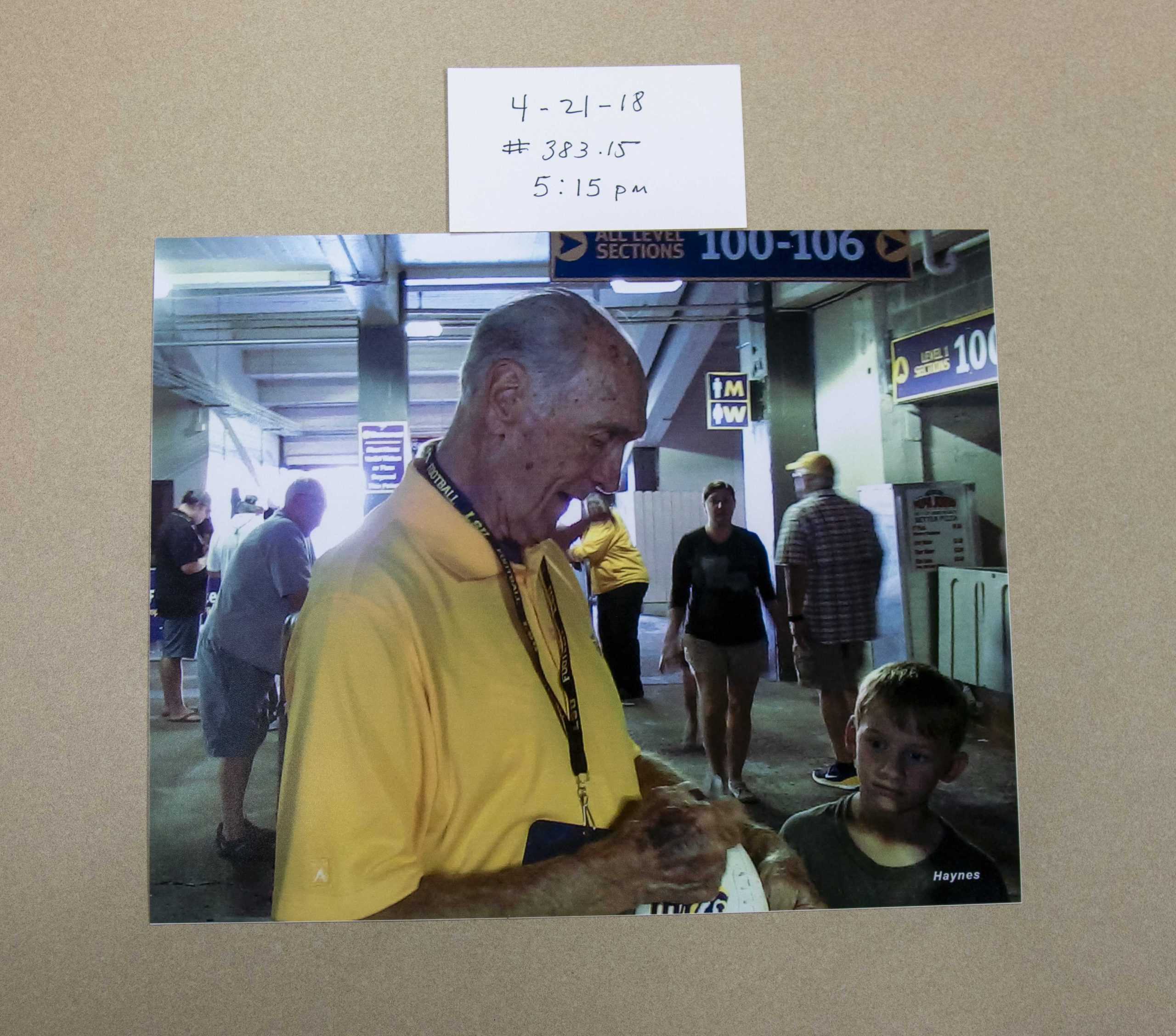

Shortly after the 2018 LSU Spring Game kicked off, David Haynes stood among a group of fans in an exit tunnel of Tiger Stadium.

It was early evening on a hot, humid April day. The sun was beating, shining bright through the opening of the tunnel.

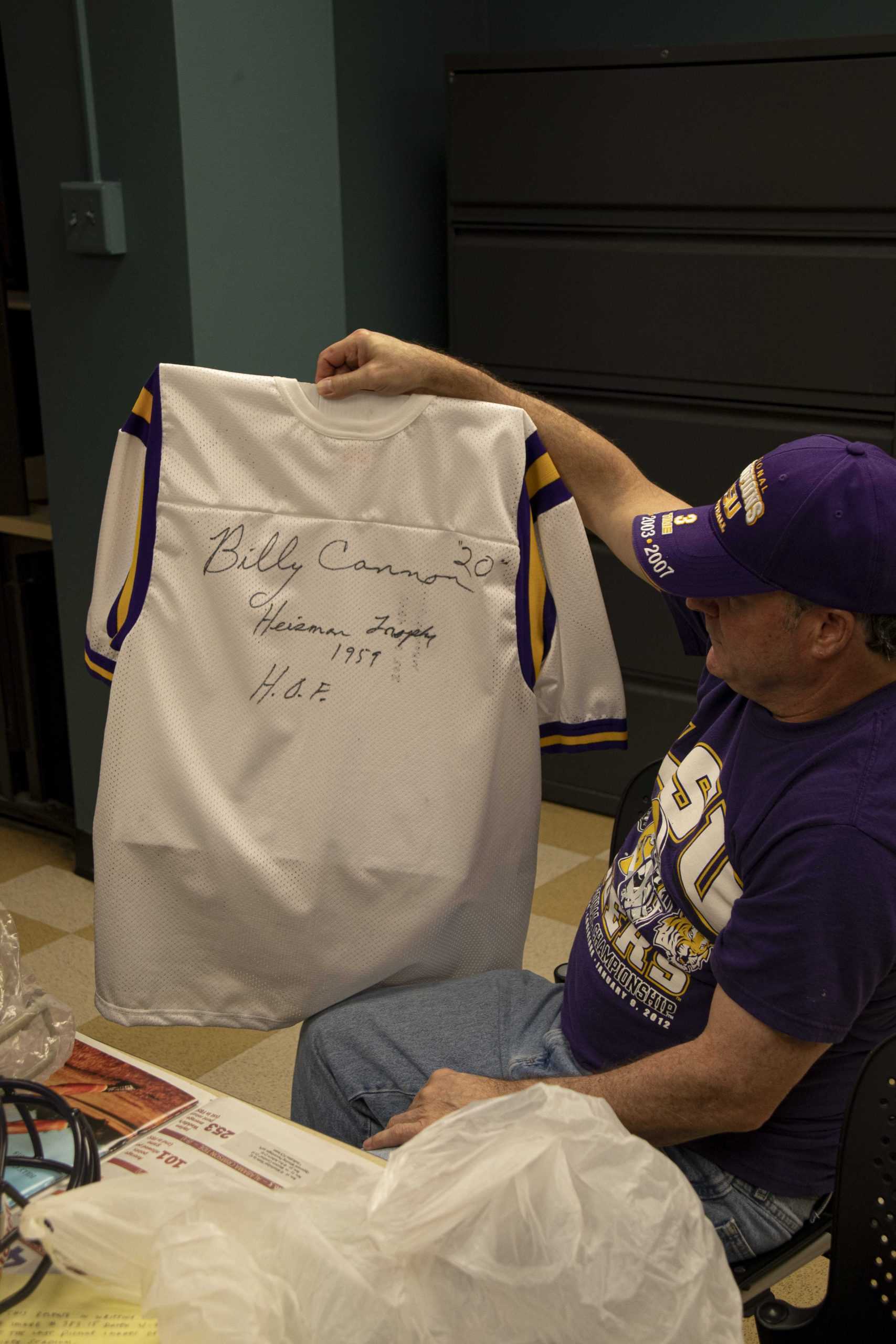

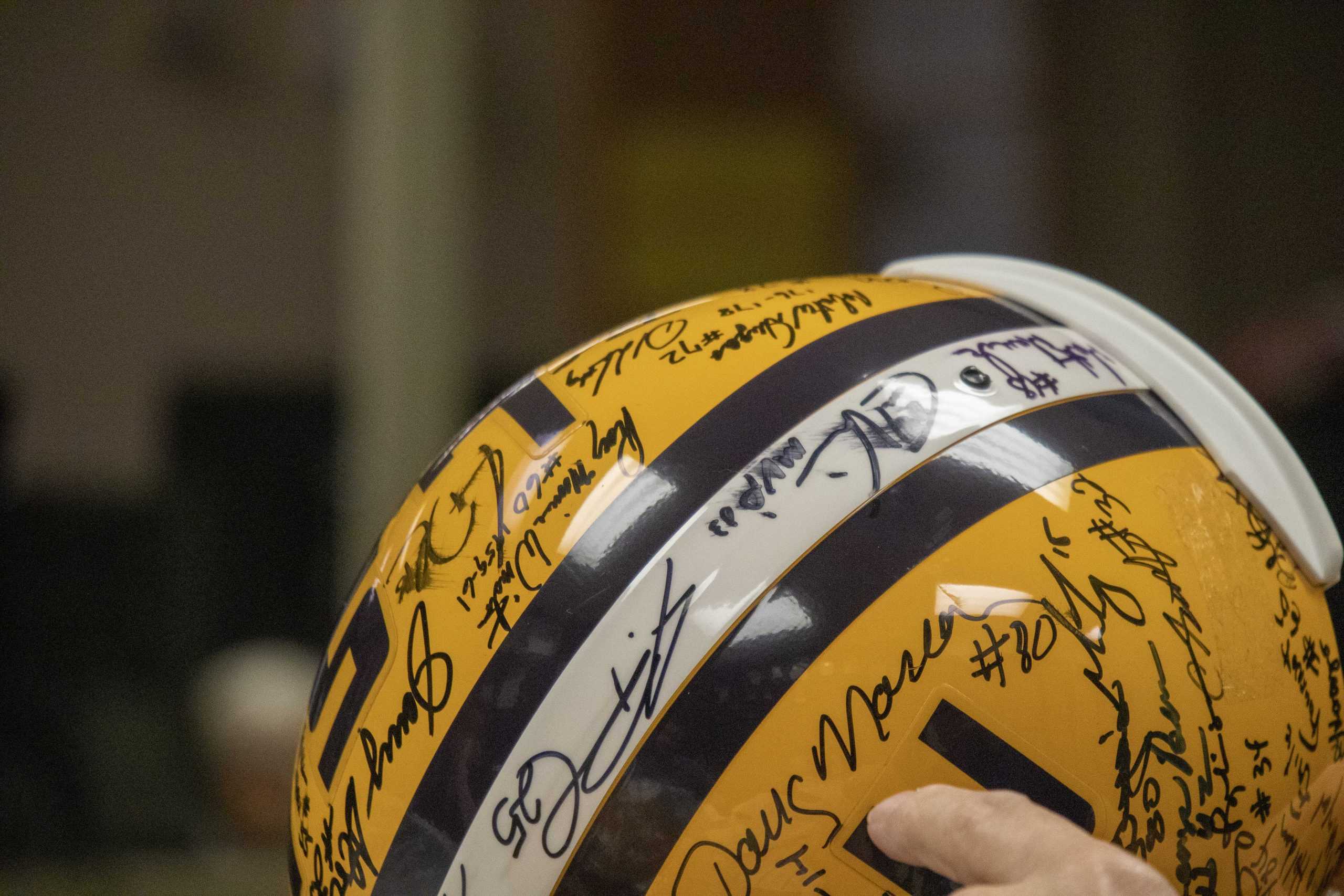

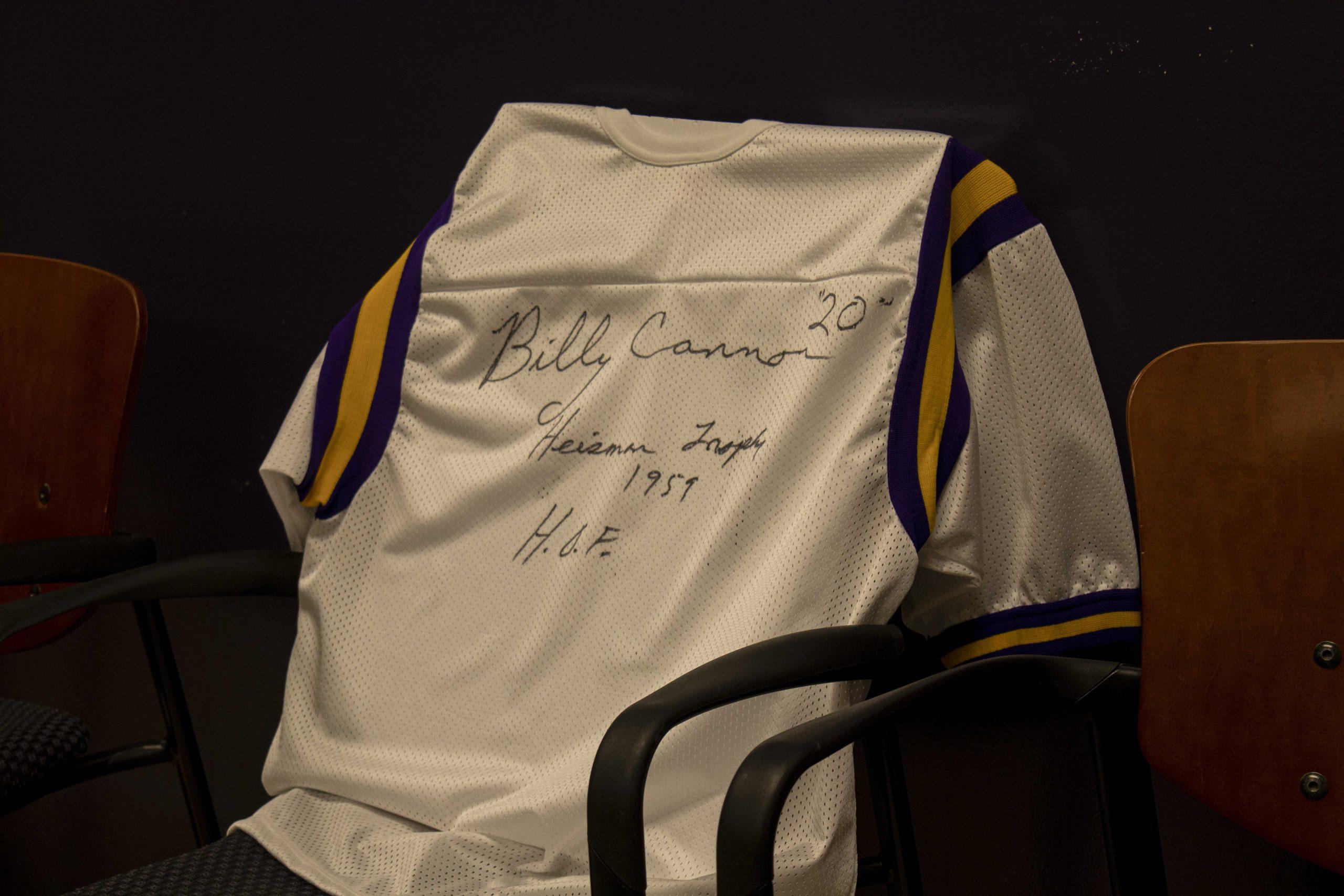

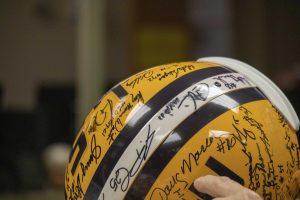

Haynes is a 57-year-old LSU superfan and an experienced autograph collector. He brought some of his memorabilia to the game on April 21, 2018, including a helmet covered with signatures from LSU football’s All-Americans. On the helmet, he saved a spot for the autograph of the only Tiger who was unanimously named to an All-American team twice, Billy Cannon. The 1959 Heisman Trophy winner was a guest coach at that spring game.

Haynes hoped to catch Cannon at the right time. So he waited.

After a few minutes, Haynes noticed a figure emerge from the light, walking toward the faithful fans. It was Cannon.

“It’s like he walked out of heaven,” Haynes said.

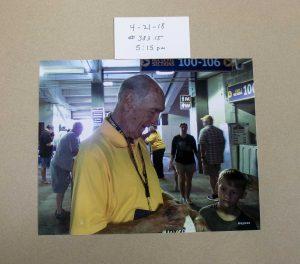

When Cannon approached the congregation, Haynes saw what was left of the once dominant athlete, the Heisman winner, the Louisiana hero. Cannon wore a yellow collared shirt. He looked thin and frail. Dark spots dotted the skin on his face and arms.

“Yeah, you do have a lot of signatures. But my eyes are so bad, I’m getting old, and I can’t see,” Cannon told Haynes.

Haynes read to Cannon some of the names on the helmet.

“Mr. Cannon,” Haynes said, “Don’t worry about your eyesight because everybody in Tiger nation knows you’re a legend.”

Cannon’s hands shook as he signed the helmet. Haynes thanked him, wished him good health and stepped aside. Haynes snapped a photo of Cannon signing a football for a couple of children, and followed closely as he walked out of the exit gate and climbed into a car. He says he didn’t see Cannon sign any more autographs, and no one took another photo of him. Haynes began to cry.

“I looked at him, and I said that’s a legend leaving LSU Stadium,” Haynes said. “He’s a one-of-a-kind legend. It made me cry because I knew he looked a little frail. And I said I hope that he’s OK in his health.”

Cannon was driven to a different gate, where he watched the rest of the game from a suite. After the game, he left the stadium and spent most of the next month on his farm in St. Francisville, Louisiana, with his family and his horses. The 2018 Spring Game was his final visit to Tiger Stadium, his final official LSU event and his final time at the site of the most famous punt return in college football history, Cannon’s 89-yard house-call against Ole Miss in 1959.

After his run, he was a hero. Over 20 years later, after his arrest, he was a villain. He later found redemption in his interactions with LSU faithful and regained his status as a beloved icon. Haynes considers himself fortunate to have documented some of Cannon’s final moments in the company of fans in Tiger Stadium. He has one of the last Cannon autographs the Tiger legend signed in Death Valley, along with one of the last photos of the legend in the stadium.

“When I saw him, my heart jumped,” Haynes said. “I’ve met him a lot of times before and I’ve talked to him before, but it was just something special about that day and that sunshine.”

“That was meant to be. This was special because for some reason this was different. It was a different vibe that I caught that day.”

On May 20, about a month after the Spring Game, Cannon passed away. On May 18, a couple of days before Louisiana lost its only Heisman winner, an unknown backup quarterback from Ohio State transferred to LSU in hope of resurrecting his career. His name was Joe Burrow, and he announced his decision in a tweet.

“Excited to be playing in Death Valley next season,” he wrote. “Ready to get to work.”

——-

Bill Ferrari sits on the second floor of the Barnes & Noble at LSU, thumbing through a Billy Cannon biography he pulled from a shelf.

He sports a purple LSU baseball cap, a black and purple LSU leather jacket and a purple shirt with “LSU” emblazoned in gold across the chest. Ferrari studied history and anthropology at the University in the late ‘50s.

And he stood in the stands for the Tigers’ fabled game against Ole Miss on Halloween night in 1959.

Ferrari saw the moments Cannon became a Bayou rock star, as he sprinted down the sideline on his punt return touchdown, leaving would-be tacklers in his wake. Ten minutes later, Cannon ran on the goal-line parallel to the line of scrimmage before leaping to stop a Rebel from scoring, preserving an LSU victory in the closing seconds of the game.

He remembers each play of the goal-line stand as if it happened yesterday.

The Tigers stopped a handoff to the right on first down, Ferrari recalled. A quarterback sweep to the left with two lead blockers on second down and another quick handoff up the middle on third down followed before the play that ended the “Game of the Century” and punctuated Cannon’s legendary performance.

Ferrari left LSU in 1961 and returned to his home in San Francisco, where he worked as a teacher for 30 years, retired and travelled the globe. He didn’t return to Baton Rouge until this football season, when he came to LSU to see Tiger Stadium, or as he calls it, the “cathedral of college football.” He watched the Tigers beat Utah State, Florida, Arkansas and Texas A&M.

He witnessed quarterback Joe Burrow become a legend, jogging onto the field on senior night to a roaring ovation, wearing a jersey that read “Burreaux.” Burrow would later dismantle Texas A&M, concluding a record-setting season in command of one of LSU’s greatest teams.

Like Cannon’s punt return, Burrow’s coronation was captured on video. Contrast the two moments, and you’ll watch one through black-and-white, grainy, shaky footage, the other through a crystal clear, steady lens. The technological gap spans the 60 years between LSU’s two Heisman winners.

Compare them, and you’ll see one clip you’ve likely seen many times before, and another you’ll likely see many times in the future. The two videos bookend Ferrari’s life as an LSU fan, six decades that were filled with ups and downs and twists and turns before ultimately ending in the same manner in which they began.

Ferrari struggles to compare Cannon and Burrow. He knows so much more about Burrow. He commends him for his humility, confidence and focus.

“He’s one of these guys everybody likes,” Ferrari says. “[The fame] didn’t go to his head at all.”

Ferrari is then shown a video of Burrow leaving the field after his Tigers routed Texas A&M. In the clip, Burrow begins his jog as the band’s playing of “Let us Break Bread Together” reaches its crescendo. Ferrari watches the quarterback bow his head and thank LSU faithful in front of the student section, the same place Ferrari watched the birth of Cannon’s legend. Burrow then moves through the thick crowd to the locker room.

“I touched him!” a young woman exclaims in the video.

Ferrari smiles.

“Like a rock star,” he says.

——-

David Haynes had met Billy Cannon before.

He says his father, Richard Haynes, lived down the block from Cannon and befriended him at Istrouma High School before they graduated together in 1955.

One day, as Cannon signed an autograph for him, Haynes asked Cannon if he remembered his father, Richard. Cannon did, and he asked Haynes how his father was doing.

At another event, Cannon and Haynes met again. Before Haynes could reintroduce himself, Cannon asked him the same question.

“How’s your daddy?” he said.

Richard Haynes attended the Halloween game in 1959. When he told the story of Cannon’s punt return to his son, he included details, like the referee sprinting alongside Cannon, and a photographer rushing into the end zone in a desperate attempt to document the historic feat. Through the memory and through the story, Richard Haynes passed on a reverence for Cannon, and by association, LSU football.

David Haynes has an entire room of his home dedicated to Tiger memorabilia. He has helmets, footballs, photos, commodity posters, 52 jerseys and a huge banner that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the 1958 National Championship. Cannon signed the banner and a plastic replica helmet that Haynes painted to look exactly like the one Cannon wore.

After he lugged a fraction of his collection into The Reveille newsroom, Haynes stood for the hour-long interview, excitedly describing his relics, his interactions with Cannon and his LSU fandom.

People like Haynes helped Cannon return to Tiger Stadium.

Cannon was arrested in 1983 for his involvement in a counterfeiting ring that had printed roughly $5 million in counterfeit bills. He agreed to cooperate with the investigation, pleading guilty to one charge of conspiracy and possession of counterfeit bills. He was sentenced to five years in prison and was released after serving nearly three years.

Cannon’s youngest daughter, Bunnie Cannon, who works for the fundraising wing of LSU Athletics, said, “He paid for it financially. He paid for it in time, and it took a long time before the community accepted him back.”

A Sports Illustrated article written around the time of Cannon’s arrest labeled him a “counterfeit hero.” He also reportedly had a falling out with LSU and former Athletic Director Carl Maddox over his seats in Tiger Stadium. Many, to this day, still struggle to find a motive for Cannon’s participation in the scheme.

“A lot of people think they know him, and they didn’t,” Bunnie Cannon said.

Both Haynes and Bunnie Cannon agree that Cannon’s contributions outweigh his criminality. After prison, he brought his dental practice to the Louisiana State Penitentiary, more commonly referred to as “Angola,” serving inmates for 22 years.

“Everybody will make mistakes,” Haynes said. “Nobody’s perfect. I forgive him for that. Look at all he’s done for Angola, for all the inmates. I think he’s well paid back society.”

Cannon slowly emerged from isolation in the years following his release. He began to open up again, signing autographs, appearing at events, speaking in front of crowds. Tiger fans like Haynes welcomed their hero back with open arms.

“He began to meet people again and to talk again,” Bunnie Cannon agreed. “And he never turned an autograph away, never turned a person away and spent countless hours trying to help further this university in any way that he could.”

“He always took his time,” Haynes said. “He always took pictures. He always signed everything you had. If there was a line around the building, he would stay there until everybody got their signature and would not leave. He was really somebody who really represented LSU.”

Haynes feels fortunate to have documented some of Cannon’s final moments in the stadium he helped build and among the fans who helped build him back up.

“He was a special person,” he said. “He really was.”

“I wish he was still here,” Haynes said with a sigh.

His photo of Cannon might be his most prized possession, but it won’t complete his collection. Haynes is in search of an elusive signature from another LSU legend. He doesn’t know where to find that backup quarterback from Ohio, but he will undoubtedly try to get his autograph.

“It’s number one on my list,” he said. “I will cherish it.”

Cannon connection: Detailing the 1959 Heisman winner’s final day in Tiger Stadium, connection to Joe Burrow

By Reed Darcey

December 10, 2019

David Haynes gazes upon a helmet signed by many players of LSU’s past in the Reveille News Room in Hodges Hall on Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2019.

More to Discover