In a speech following the signing of several environmental executive orders, President Joe Biden said he aimed to help “the hard-hit areas like Cancer Alley in Louisiana or the Route 9 corridor in the state of Delaware.”

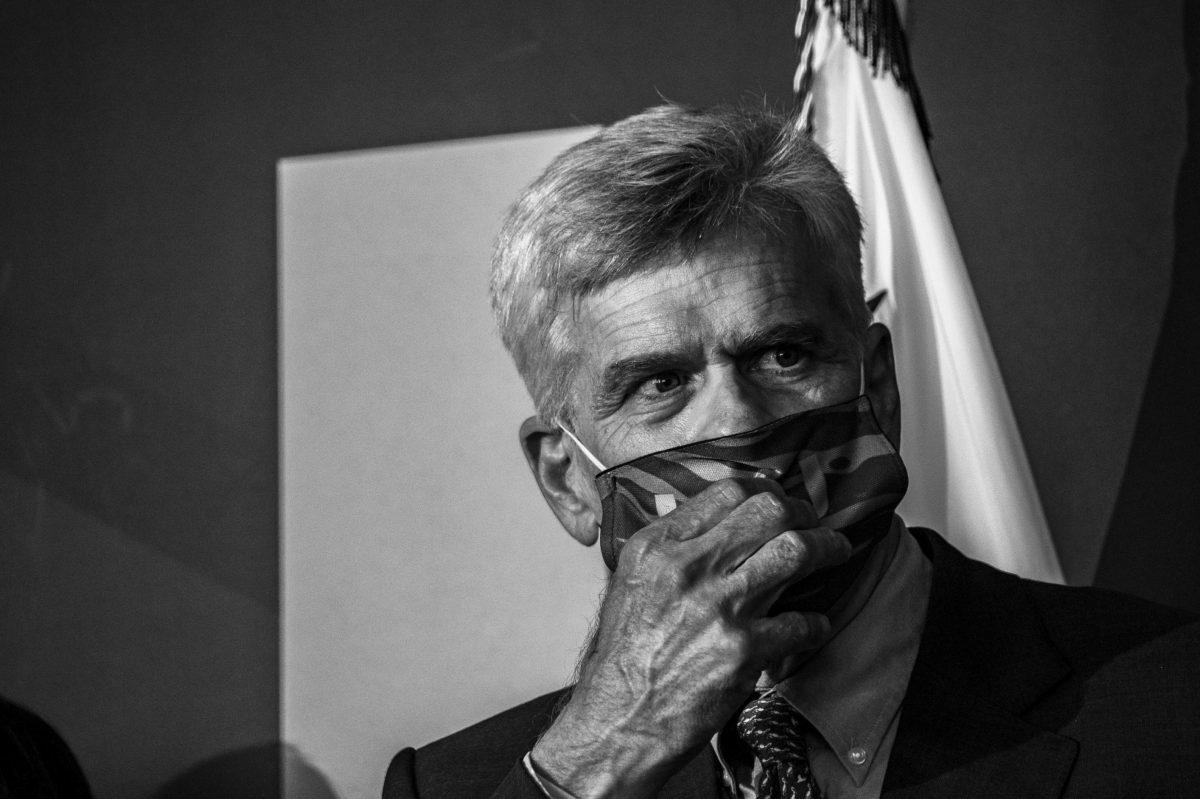

Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy hit back against the president’s statement, calling his use of the term Cancer Alley “a slam upon our state” and going on to say that “propagating the myth of Cancer Alley is not only dangerous but is an affront to the people of our great state who work tirelessly to make the industry cleaner, safer and more efficient on a daily basis.”

Sen. Cassidy also denies the industry’s role in delivering Louisiana the second-highest rate of cancer and fifth-highest rate of cancer mortality in the nation, instead attributing these rankings to ”lifestyle choices.”

Cassidy, a medical doctor whose specialty is in gastroenterology, fails to acknowledge the very real, very shocking statistics associated with the river communities in this region.

Cancer Alley, also nicknamed Death Alley by some residents and activists, refers to the petrochemical belt that stretches from Baton Rouge to New Orleans. The region holds a troubled history of environmental racism and loosely regulated pollution.

Around the 1950s, local politicians pushed Louisiana toward industry, anxious to turn the economic fortunes of the state. These new petrochemical plants were, by no mistake, built in predominantly Black communities.

As written by the Foundation for Louisiana president and CEO Flozell Daniels, Jr.: “There are disproportionate deaths in African-American communities inherently linked to historic environmental injustice. Industry pollution has historically been permitted to function in African-American communities.”

One of the most affected areas is St. John the Baptist Parish, which contains the Denka-Dupont plant. This plant produces the synthetic rubber neoprene and releases large amounts of a chemical known as chloroprene, a likely human carcinogen according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

In St. John Parish, chloroprene levels are 40 times the EPA’s acceptable level, and the cancer risk is an appalling 800 times the EPA’s target, making it the highest cancer risk in the entire United States.

One day, EPA chemical readings showed levels of chloroprene 765 times the acceptable level. Tests of local schools have regularly shown chloroprene levels dozens of times the appropriate limit. In fact, the five highest-risk areas of cancer in the nation are all located in St. John Parish.

While Dupont publicly claims the chloroprene release poses no risk to the community’s health, an internal memo shows that the company was aware of the chemical’s lethal and toxic effects in 1941, 69 years before it would be declared a likely human carcinogen by the EPA.

Residents were rightfully outraged by these findings, wondering how the Denka-Dupont plant could be allowed to exceed the 0.2 micrograms per cubic meter limit so easily.

When asked why this was the case, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality simply responded that this number was just a “guidance,” and not “an emissions limit.” In other words, this corporation’s gross polluting of St. John Parish is perfectly legal, unchecked by the state and federal government.

St. Gabriel, a predominantly Black city in Iberville Parish, has also felt the impact of pollution. A hospital receptionist there shared with ProPublica that out of every 10 houses in the city, there were one to two cancer deaths. Residents reported the nighttime chemical release leaves birds dead and coats lawn in yellow mist.

And as much as proponents of industry like to claim that the economic benefits outweigh environmental concerns, the actual residents of St. Gabriel saw little of these supposed gains.

A 1995 survey found that less than 9% of plant employees were from the community itself, the rest made of outside hires. One resident remarked to ProPublica:

“We thought we’d get better jobs, but they brought their own people here. They’d say we can’t pass their tests; that we’re on drugs.”

Today, poverty is a persistent issue in St. Gabriel Parish, and environment-related health concerns remain top of mind for many residents.

The consequences of this air pollution have become even more severe with the onslaught of the pandemic. St. John Parish has some of the highest COVID-19 death rates in Louisiana; in April, it had the highest COVID-19 death rate per capita in the nation.

Environmental factors contribute to the disproportionate COVID-19 infection and mortality of Black Americans. In fact, researchers have argued that chronic exposure to air pollution should be classified as a high-risk factor for COVID-19.

Much more research needs to be done in the communities that occupy the region known as Cancer Alley, especially since industry powers use this lack of research to suggest that there is no problem at all.

Industry allies, including Sen. Cassidy, have turned to the state’s tumor registry as an attempt to dismiss health concerns linked to petrochemical plants. But the census tracts used to aggregate the registry isn’t the best metric to go by, considering these areas vary in size and emission levels, and privacy limits prevent the publishing of information in less populated areas like St. Gabriel, meaning there are gaps in the data.

Attempting to say that the tumor registry avails industry of any wrongdoing is simply inaccurate. Meanwhile, the data made available by the EPA over the last number of years shows cause for great concern.

This data shows that petrochemical plants in Louisiana have been allowed to pollute communities, especially low-income and Black communities, for decades with little consequence.

It also shows that pollution puts exposed residents at unique risk for cancer, respiratory illness and now COVID-19. So why, then, is Cassidy determined to place the sole blame of Louisiana’s cancer crisis on its residents?

Questionable intent lurks behind Cassidy’s outright dismissal of industry’s role in the state’s health outcomes. For his 2020 reelection campaign, the senator raised over half a million dollars from the oil and gas industry, with $226,800 of that coming from PACs.

In fact, more than 88% of all funding for his campaign came either from PACs or large individual contributions. Put simply, Cassidy is not funded by the low-income communities disproportionately impacted by the pollution he rejects.

Cassidy is being financed by industry, and Louisiana residents are paying the price. This state deserves leaders that stand up to corrupt corporate powers, not ones that parrot their talking points. To ignore the obviously well-founded concerns of his constituents is a severe disservice.

President Biden recognizing the existence of Cancer Alley is not “a slam upon our state” or an “affront,” as Cassidy claimed. What is very much so, however, is the senator’s determination to let the corporations polluting Louisiana communities off the hook.

Claire Sullivan is an 18-year-old coastal environmental science freshman from Southbury, CT.