An archive of never-before-seen letters by the late Troy H. Middleton, LSU’s segregationist president of the 1950s, has recently been revealed. A quick look into this archive by The Reveille exposes Middleton’s disappointing yet unsurprising sentiments toward equality and desegregation.

In fact, what’s revealed is that Middleton apparently only relented to desegregation at LSU because it was federal law and he had no choice but to. That is, without two student lawsuits and federal intervention in the form of Brown v. Board in 1954 and Louisiana v. United States in 1974, LSU would still be a sea of white — even more so than it is today.

Yet because of the racism perpetuated by Middleton and his ilk, Black Americans for the longest were left to their own devices when it came to pursuing a quality higher education (among many other things). In fact, it is thanks to P.B.S. Pinchback, Theophile T. Allain, and Henry Demas that Black students even had (and still have) a preeminent university of their own to attend. These brothers stepped up and petitioned the Louisiana Constitutional Convention in 1879 to create a university for Black students, which then manifested in the form of Southern University in 1890.

For those who don’t know, there’s a reason historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) exist, and Southern is emblematic of why.

Though Southern was created for Black students who were systematically rejected by LSU, it was still a far cry from equality and hardly absolved all of the resultant hurt and pain. The sober reality is that there weren’t any Black students at LSU until 1950, when a prospective student sued the law school. Up until then, it had been “official policy of the L.S.U. Board of Supervisors that no black students could attend the law school at L.S.U.” It wasn’t until a year later that the Graduate School was desegregated. And it wasn’t even until after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ten years later that “Louisiana discontinued its official recognition of the state universities as single race institutions.”

Roy S. Wilson was that prospective law student, and Lutrill Payne Amos Sr., was that prospective graduate student. Wilson sued LSU’s Board of Supervisors in Wilson v. Board of Supervisors in 1950. Because Southern had already been created for Black students and had its own law school, LSU argued, they felt that Wilson, who was Black, had other options and denied him admission.

But the Federal Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana wasn’t buying it and ruled in favor of Wilson. Because LSU and Southern didn’t have equally prestigious law programs — LSU law was superior to Southern law in terms of resources and post-graduation job prospects — LSU’s rejection of Wilson simply because he could also apply to Southern violated his 14th amendment right, one of the Reconstruction amendments to the Constitution that guaranteed Black Americans equal protection under the law. So Wilson won and was admitted — technically. (He either enrolled in non-credit courses for fall 1951, never received his grades, and didn’t register for spring 1952; or “he was expelled before he entered. . . .” Yeah, right.) Rather, it was Lutrill Payne Amos Sr., a 41-year-old father, who was the first to integrate LSU, in 1951. Amos — a World War II veteran — had been admitted to the College of Agriculture, but had had his admittance rescinded after sending “the required photograph of himself.” He promptly sued LSU (just a year after Wilson did) and was admitted to the College of Agriculture in 1951 as a graduate student (he had already earned a bachelor’s degree at, you guessed it, Southern.) Thanks to Roy S. Wilson, and subsequently Lutrill Payne Amos Sr., LSU has undoubtedly benefited from them and the Black students — including athletes — who have followed in their footsteps over the last 70 years. Unsurprisingly, though, the situation is still far from perfect. MLK talked about two Americas. Well, Louisiana was not far behind: with its historically white university (LSU) and its historically Black university (Southern), it “established and maintained a dual system of higher education based upon race.” It’s difficult to overstate the effects of such a pernicious web of inequality.

As far as we know, though, things could have been much worse. Fortunately, Wilson wasn’t fighting alone. Not only was Amos on his side, but so was Brown v. Board, and, later, United States v. Louisiana. Louisiana was sued by the United States in 1974, precisely for its “unlawful dual system of higher education based on race.” After some back-and-forth negotiating, Louisiana and its system of higher education — most notably, LSU — agreed to parental oversight for its childish behavior by entering into a Consent Decree in 1981 with the U.S. government; in it, Louisiana was admonished to clean up its racist and discriminatory act. The terms of the Consent Decree are listed below. Since LSU was part of the Decree, it had committed to:

1. Shaping the process of admissions and recruitment to increase the number of “other-race” students;

2. Solving the problem of student attrition (especially with respect to “other-race” students);

3. Resolving the issues and problems arising out of program duplication; and the allocation of program curricular offerings among the state’s institutions;

4. Understanding the appropriate role of historically black colleges and making provisions for their enhancement; and

5. Taking substantial steps to achieve a more equitable balance in the racial composition of the staff, faculty, and governing boards of the university system. Results were abysmal and, as a consequence, the Consent Decree had to be renewed in 1987. Not all of the 1981’s Consent Decree had been implemented and “almost all of the state’s institutions of higher education remained racially identifiable [emphasis mine]”. Two years later, in 1989, the Decree was declared ineffective and LSU was forced to merge its law school with Southern’s. From 1971 to 1989 enrollment of Black students at LSU rose from 0.1% to 7%. In that same time period, there were 55 Black graduates from LSU’s law school, which represented 1.31% of the total graduates. Black students now comprise 9.1% of the law school.

Alas, despite all of the inequality, some Americans were (and still are) okay with it. In fact, men like Middleton were okay with it and wanted to perpetuate it. Thus there’s a historical perspective: Without Wilson’s and Amos’s lawsuits and later federal intervention in the form of Brown v. Board and Louisiana v. United States, anti-Black politicians and high-ranking officials would still be free to do as they please: discriminate against Blackness.

Stretching back to at least the Constitutional Convention in 1787, there has been a visible pattern: states — and those who run them, which are often men — will only acquiesce when they have to. (And when they don’t, or at least prolong the process, lives are at stake.) All the while, they seek to evade the federal government and run their oppressive state regimes unchecked. Thus a common refrain among men like Middleton who perpetuated segregation was that they would only acquiesce when they absolutely had to. That is, as The Reveille quotes Middleton as saying, they would stand down (read: treat Black Americans as humans) only when they were “in no position to violate the order of a Federal court.” People like Middleton needed to be checked by the thumb of the federal government.

Some, however, still live in this fantasy land where the federal government is the bogeyman that impedes their ability to continue doing what they want to do: discriminate. These people either don’t see the detriment or otherwise fail to acknowledge its impact. That is, “The society either pretends it does not know . . . or is in fact incapable of doing anything,” in the words of Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton. Fortunately, major civil and human rights legislation in recent memory at the federal level has corrected for this. From the Reconstruction amendments to the Civil Rights Movement and beyond, states have been proscribed from perpetuating a host of racist and discriminatory practices. (Well, at least semi-proscribed.)

People like Middleton live in a world where, if the federal government didn’t stop them from doing it, and where if they didn’t have to align themselves “pursuant to court orders,” segregation, racism, and discrimination would have continued unimpeded. A world from which we are only two generations removed. A world which, in fact, still lingers around today thanks to actions such as the Supreme Court, who gutted the pre-clearance section of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 that had required states to prove that what they did in the past — prevent Black voters from voting — was not what they were still trying to do today.

If Middleton and people like him weren’t stopped, minorities and women, as a result, wouldn’t have the civil and human rights protections they’ve come to know; and the Constitution would nary apply to them. In fact, without pressure, sentiments like this would still be expressed as the status quo: “To be specific — L.S.U. does not favor whites and Negros participating together on athletic teams.” These are the words of, you guessed it, Troy H. Middleton. Here’s more: if Black students went into the swimming pool, “we would, for example, discontinue the operation of the swimming pool.” What? This was the president of a university — a place where intellectualism is supposed to thrive.

Damaging as they were, Middleton’s comments were par for the course, and well before he assumed the presidency of LSU, the movement for Black lives had already been working to tear down the white structure he and people like him sought to uphold. The movement was comprised of Black men and women, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, and grandchildren and grandparents — and students. It started before our nation’s founding and has continued in full force ever since. Mary McLeod Bethune and A. Phillip Randolph, for example, birthed Executive Order 8802, which banned discrimination in the defense industry in 1941. And A. Phillip Randolph and Grant Reynolds birthed Executive Order 9981, which banned segregation in the military in 1948. (Imagine what it must have felt like to fight for your country on someone else’s turf in the name of liberty and freedom only to be denied liberty and freedom at home, on your own turf.)

Sad but true, well before his time and, indeed, well after his time, men like Middleton only acquiesced when the letter of the law forced them to. That is, when Roy S. Wilson and Wilson v. Board of Supervisors in 1950 forced them to. When Lutrill Payne Amos Sr., forced them to. When Brown v. Board in 1954 forced them to. And when United States v. Louisiana in 1974 forced them to.

We’ve had a problem of allowing states and institutions to install folks like Middleton into positions of power. But when that happens, they incubate hate, and we have much to be ashamed of: the gang-rape of 14-year-old Recy Taylor in 1944; the lynching and slaying of Emmet Till in 1955; the killing of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in 1964; and the embarrassment of Bloody Sunday a year later in 1965. The list, of course, goes on.

Alas, though racists and segregations have begun to acquiesce to the letter of the law, there’s still a long way to go. Yes, we’ve been able to chip away at the mountain of inequality that divides us, but as MLK said, one America “is overflowing with the milk of prosperity and the honey of opportunity.” In the other America, our brothers and sisters “find themselves perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.” MLK’s words still ring true, and the reason why is because, as Malcolm X said, “We can never get civil rights in America until our human rights are first restored. We will never be recognized as citizens there [in the U.S.] until we are first recognized as humans.”

We’re far from it, but we’re closer to equality. Closer to mending our two Americas and restoring everyone’s human rights. Racists and segregationists have tried stopping it, but the movement for Black lives keeps marching on — it has no choice.

Sadly, Middleton’s world isn’t completely in the past. States are still wielding their power to incubate hate even today. They continue using their power to value property over lives, such as in the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. And they continue using their power to value whitewashed history over accurate history, such as in Texas’s Senate Bill 3. The list goes on.

It’s as if the ghost of Middleton is coming back. Or, did it just never go away?

LSU and countless other universities, cities, and states across the country are still infected with the ghost of Middleton. And it’s precisely because our history and people like him seem to be lost on them. Instead of reviling Middleton’s actions and that of those like him, the powers that be have simply adopted new ways of doing what he did, whether intentional or not. That is, they’ve gone from de jure discrimination to de facto discrimination. What was a hard color barrier of the 1950s is, for example, perhaps a soft testing barrier today. In the past, your photo was used against you; now the rigid application process and your test scores will be used against you. That is, a segregationist would out-right disallow Black students from applying; now they “welcome” your applications — but they do so within the framework of a system that doesn’t adequately account for the actions of our past: discrimination. Rather than a holistic approach to evaluating applicants (none of whom have the same amount of resources to game the system to look good on paper) the system constrains you through its rigid and inadequate application process — not the least of which is its narrow-minded focus on test scores.

This system inevitably — and perhaps by design — privileges those who have the resources to do well. It’s a 21st-century version of the Matthew Effect: those who have the resources to do well are likely to do well, and because they do well they’re likely go on to experience an outsize effect as a result of doing well. In other words, the rich get richer. Those who don’t have the resources, well, where does that leave them? And if the outcome today is that of being turned away from college for things which are out of your control, how is it that much different from Middleton’s world? “The line between purposeful suppression and indifference blurs,” as Ture and Hamilton lamented in 1967.

We have a long way to go, but exposing racism and segregation across the nation and here at LSU is the least that can be done. Alas, “Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightning.” Frederick Douglass went on to say, “They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.” Acknowledging and revealing those who wielded their power for evil is the right thing to do.

Middleton is long gone, but his legacy and that of those like him isn’t. The damage is still here. The effects don’t go away. He used his power to hurt countless Black lives — brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, and in the case of Amos, a father. That power is dangerous, and though in different forms, it’s still being wielded today.

What was the beating, killing, raping and out-right racial discrimination of Black men, women, and children in Middleton’s day are perhaps the drug laws, city planning meetings, infrastructure dealings, policing, and rigid application process and narrow-minded testing of our day — all of which are touted as colorblind and neutral yet clearly help some and hurt others. Perhaps that’s the point. . . .

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

–Langston Hughes

Guest Opinion: Legacy of segregation era lives on today at LSU

July 30, 2021

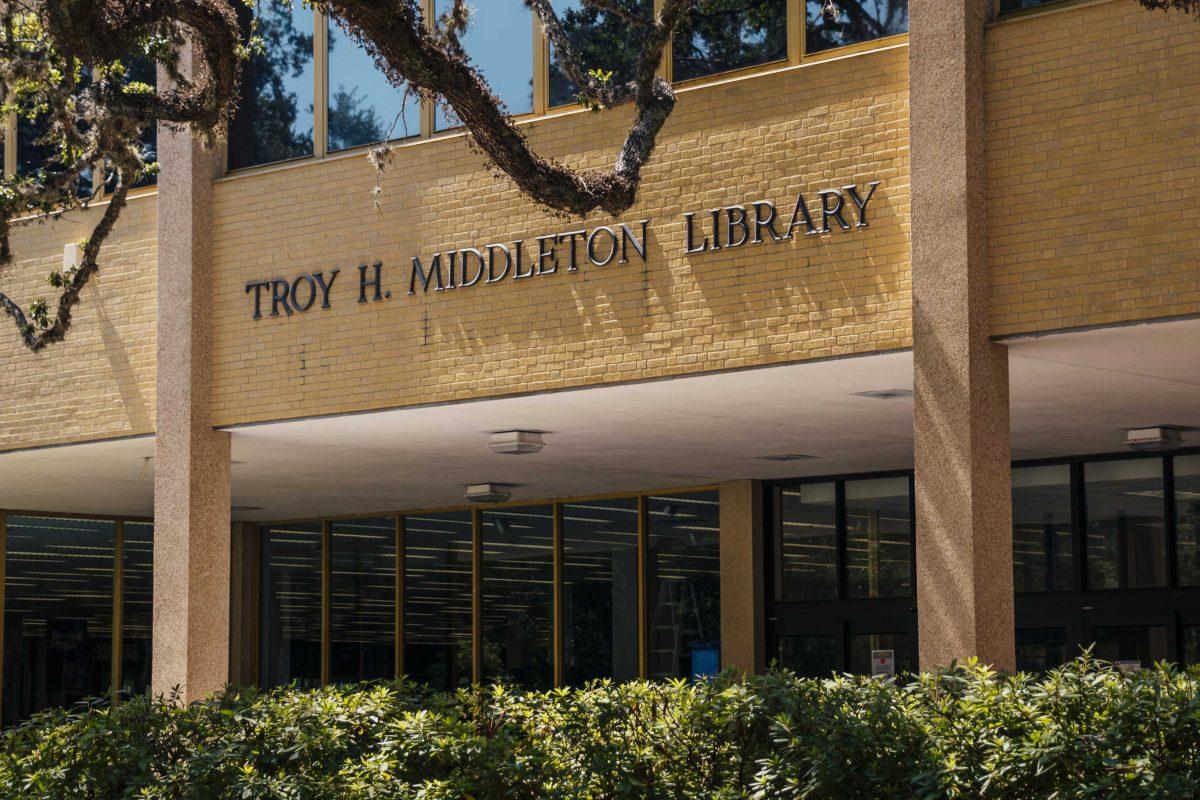

Troy H. Middleton Library—the first subject of building renaming efforts, now named LSU Library—on June 17, 2020, on LSU’s campus.